A Short History of Evolution: The Gods of War

This article is part of Carl Coon’s ongoing “A Short History of Evolution” series. Click here to read all entries in this series.

During the Neolithic Era the rate of change, or progress as some people call it, sped up considerably. It was like a car shifting into a higher gear. But even so, village life was conservative by our standards. If it had taken our ancestors as long to get out of the Neolithic as it took their Upper Paleolithic ancestors to get into it, we might still be living in villages and using stone tools ourselves.

One thing led to another. When one problem was solved, several new ones would emerge in its wake. It was the same old principle, the simpler leading to the more complex, but like Beethoven’s Eroica variations, that same theme kept reappearing in very different forms.

It’s not easy to distinguish between cause and effect here. It’s like a stew on the fire that slowly begins simmering and then comes to a boil. Which ingredients had to come in first? Perhaps that’s not as important as the fact that once the process started, they were all in the pot together.

The bottom line is that human intentionality combined with favorable environments to produce increasingly large groups of individuals who were willing to cooperate for the common good, even at some personal cost.

Let’s take a closer look at a critical juncture, the transition separating the Neolithic from what used to be called the Bronze Age. What were the critical factors that propelled a sleepy village society from a stately andante to ever more rapid tempos?

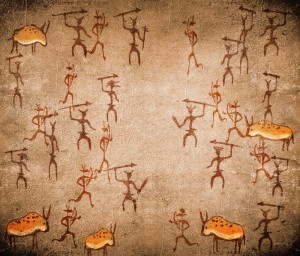

War as an Agent of Cultural Change

From an evolutionary perspective war served as a kind of subset of the more general principle that one thing leads to another. Thus war leads to peace, and peace, once the dust settles, leads again to a new war. Usually people learned something during each cycle, even if it was only how to make war more efficiently. When the cycle ended there had been progress, in the sense I defined it back in Chapter One.

War is such a recurrent theme in the vast tapestry of human history that we cannot dismiss it as just another flaw in human nature. Something else is at work here, some feature basic to the evolutionary track our species was following.

Here are some of the more obvious reasons why war assumed the role it did in the early cultural evolution of our species:

–Whatever the proximate causes of the conflict, war usually resulted in the victors getting bigger, both in resources and in territory. As the groups grew in size, their capacity to provide for their citizens grew also. But problems of governance grew more complex as well. The emergence of new problems created new demands for new workarounds and new institutions.

–The victorious units were able to use slavery to add to their existing power base. Slaves could do jobs domesticated animals could not. They built roads and palaces, and almost everything else that required intensive labor. The more nubile females among the losers often ended up as concubines for the victors, providing a back door route to both genetic and cultural hybrid vigor.

–War provided an enormous stimulus for technological innovation. If your team lost a battle because the other team had bronze weapons and you didn’t, you became powerfully motivated to acquire this new-fangled bronze technology yourself. This kind of arms race continues to this day.

–Wars were won or lost not only on weaponry but on organizational skills and discipline. Hierarchies and rules evolved rapidly and the lessons learned spilled over into civilian governance as well.

–War had a decisive effect on gender relationships. Patriarchal rule, and male dominance generally, can trace their origin not to innate human nature but to this period when wars were fought under circumstances where the male’s body strength gave an advantage.

–Perhaps most important of all, wars provided powerful support for the development of group loyalty. Problems of governance multiply as the size and complexity of the unit increases. When concern for one’s reputation isn’t enough to keep the malingers in line, the law steps in to fill the breach. When that is inadequate, and non-cooperation grows to the point that it threatens the integrity of the group, there’s nothing like a good brisk war to get everyone marching in step. Fear of conquest by some alien force is a powerful motive for cooperation.

War didn’t evolve by itself, any more than altruism did at an earlier stage in our evolution. One essential partner for war was religion, which co-evolved with it.

The Problem of Motivation

During the Neolithic Period, increasingly complex hierarchies evolved separating commoners from the monarch and his community of aristocrats. When war came, the lords lorded over the whole procedure and reaped most of the benefits, while commoners did most of the fighting and suffered the heaviest casualties. What on earth motivated the common soldier to put his life on the line for someone else’s cause?

The answer is that religion adapted to the new situation and became the prime motivator for soldiers when they faced the prospect of a sudden and bloody death. If you are about to die it helps if you believe in an afterworld. But there’s more to it than that.

The great world religions of our modern era began during periods of social unrest and frequent war. They answered many other human needs, most of them with no connection to war at all, but they each embodied symbolism that could be invoked in time of war: “Onward, Christian Soldiers,” “Allahu Akbar” (“God is great”), and so forth. The effect was, and still can be, that of an aphrodisiac, particularly effective with younger males. It’s still with us, the social equivalent of the adrenalin rush that an individual gets when facing sudden danger.

That adrenalin rush is part of our human nature. Its use as a facilitator for war is, however, a cultural adaptation. This means that war is not inevitable at all times and under all circumstances. It is a cultural artifact, not a genetically transmitted product of natural selection. We learned to live with war and we can learn to live without it.

The same goes for the gods of war we grew up with: Yahweh, Allah, and the more militant avatars of the Christian deity. We no longer need to see them up in the heavens someplace, “trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored.” Indeed, we’re a lot better off if we don’t.

In Defense of Group Selection Theory

The rules of the selection game changed as war became endemic. Natural selection theory could cope with competition between species over a time span based on generations, but was unable to cope with this new phenomenon of intentional competition based on much shorter time spans that occurred within a single species.

Group selection theory is a better analytical tool than natural selection in coping with this new kind of competition because it works with shorter time spans and deals with intentional factors as well as natural ones.

Equally important, it can cope with adaptations that reverberate on more than one of the several hierarchical levels that evolved as human societies became more complicated. If a specific workaround or institutional wrinkle is introduced at a group level, and it also causes happiness at the personal level, it is more likely to evolve as a permanent feature of the institutional landscape.

This kind of serendipity can be relatively simple, as with the example of prayer, or it can be very complicated. The more complex the society, the more complicated the mechanisms and attitudes needed to reinforce the structural integrity required to keep the whole edifice from collapsing. We’ll take a closer look at this presently.

This article is part of Carl Coon’s ongoing “A Short History of Evolution” series.

Click here to read all entries in this series.