Why Justices Kagan and Breyer Didn’t Go Far Enough

In a recent and highly publicized ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed that sectarian prayer may continue to play a ceremonial role in government-sponsored functions without violating the First Amendment. The lawsuit was brought by two residents of the town of Greece, New York, who argued that because opening invocations at monthly town council meetings were offered exclusively by Christian clergy and made frequent use of uniquely Christian language, the practice ran afoul of the Establishment Clause. The plaintiffs argued that, had Christian clergy prayed in such a way that would make a diverse audience feel welcome, the council would not have given some residents the impression that government was favoring one religion.

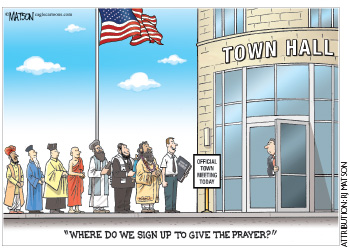

By a 5-4 margin, the justices concluded that Greece’s prayer practice was consistent with current practices in Congress and in many state legislatures across the country. Furthermore, they found no evidence that clergy who led the invocations were denigrating other traditions or trying to convert residents. And, the council did have a policy of nondiscrimination in place: leaders from any religious community could have offered a prayer, if they had so desired. They may not have sought out leaders from minority communities, but neither did they turn any of these leaders away. The justices therefore determined that council members were not endorsing Christianity but merely hoping to solemnize these occasions by invoking a power greater than themselves.

Justices Elena Kagan and Stephen Breyer authored the dissenting opinion. Kagan in particular noted an important difference between existing, constitutionally acceptable prayer practices and those employed in Greece: while chaplains in Congress and state legislatures address only elected officials, clergy in Greece directed prayers to everyone in attendance, often employing exclusionary sectarian language (“through our Lord Jesus Christ”) that suggested all residents were of one mind. The message was clear: if you belong to a minority religious community, or you have no religious affiliation, you are not one of us. “The practice,” observes Kagan, “thus divides the citizenry, creating one class that shares the Board’s own evident religious beliefs and another (far smaller) class that does not.” Had the council included leaders from minority faiths and chosen to limit the invocation to officials, she said, their prayer practice likely would not have run afoul of the Constitution.

What Kagan and Breyer didn’t consider is that prayer is a tradition-specific ritual that by its very nature excludes many religious people.

What Kagan and Breyer didn’t consider is that prayer is a tradition-specific ritual that by its very nature excludes many religious people.

The point of prayer is either to petition a deity for a favor (prosperity, good health, guidance, forgiveness) or to express gratitude for a favor already received. While prayer is central to all three Abrahamic traditions, it plays little or no role for practitioners of some Eastern traditions. A Zen Buddhist monk, Hindu yogi, or a Confucian, for example, may never pray. Meditation would certainly be important for the monk and yogi, and ancestor veneration would very likely be important for the Confucian, but prayer may play no role at all in their lives. Indeed, for Buddhists, Taoists, Jains, and Confucians generally, there is no single creator to address, so it’s hard to see how adherents of these traditions could not feel excluded when subject to the endless litany of theistic invocations offered in the town of Greece. No matter how generic a clergyperson’s address (i.e., “Creator,” “Maker of All,” “Life-Giving Spirit”), members of these traditions simply cannot participate. For many religious adherents, then, prayer itself is the problem: it’s simply not a ritual in which they have ever been—or would ever be—engaged.

Kagan and Breyer also failed to acknowledge the concerns of the nonreligious. How, exactly, does religious diversity accommodate them? No matter what kind of ritual is selected, or how many leaders of different faith communities participate, nonreligious residents remain marginalized. A recent poll conducted by the Pew Research Center suggests that nearly 20 percent of Americans are not affiliated with any religious tradition. And many of these Americans not only don’t believe in the existence of a creator but disavow a transcendent realm altogether. By praying before meetings, the council not only privileges certain religious traditions over others but also endorses religious observance as such.

Finally, as an outsider to the Christian tradition, I must admit that I find it perplexing that council members would seek the creator of the universe’s assistance on mundane matters, which we seem perfectly capable of addressing on our own. Can their Christian God really be bothered with determining rates for parking fines on Main Street, or whether Hooters should be granted a permit to build a restaurant two blocks from an assisted living center? If such a God finds Greece’s concerns more pressing than curing malaria, reducing poverty, or fostering global peace, how’s he worthy of our attention?

Should there be a creator, I say we leave him, her, or it alone to attend to far more pressing issues. We are abundantly well equipped to decide whether a parking fine ought to be $35 or $45 without God’s input.