Why Are So Many Unarmed Black Americans Killed by the Police?

In late May the U.S. Department of Justice announced strict new standards be placed on the police department of Cleveland, Ohio, after a review of its use of force against criminal suspects and others guilty only of talking back or running away from them. “There is much work to be done, across the nation and in Cleveland, to rebuild trust between law enforcement and the communities they serve where it has eroded,” stated the head of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, “but it can be done.”

There are myriad reasons why African-American criminal suspects, most of whom are male, are killed by police. Some of these reasons have roots in the revolutionary changes of the 1960s and the push to grant equal civil rights to people of color.

The slogans “law and order” and the “War on Drugs,” employed by Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan in the late ’60s and early 1970s, were designed to attract angry white men who were traumatized by the rapid social transformations of the civil rights movement. Those changes, particularly granting new rights to blacks, were felt as impinging on their way of life. These slogans were also used to crack down on, arrest, and incarcerate men of color at an accelerated pace.

As a positive backlash we have witnessed a long series of reform efforts that have made police officers unsure of themselves and more fearful, especially those who have trouble controlling their anger and keeping street encounters under control.

To more fully understand the cause of law enforcement’s disorientation, we have to consider the spotlight in recent years on the tremendous damage done to black men and their families, as documented by scholars like Michelle Alexander (author of The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness), and targeted for change by activists.

The criminal justice system is poised to undergo rapid change, namely in trying to establish alternatives to incarceration, ending “Stop and Frisk,” arresting fewer marijuana possessors, and demanding less reliance on mandatory sentencing and the death penalty. Still, the requirement to meet arrest quotas for minor offenses places enormous pressure on both the police and those they encounter during street and traffic stops.

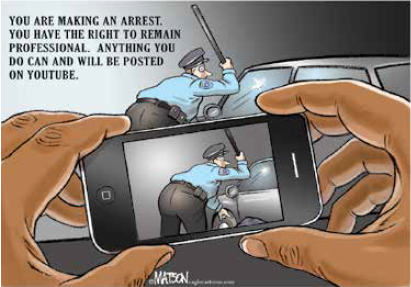

What might prove to be the most important factor causing panic among police officers is that smart phone cameras are not only exposing the killing of unarmed people of color; they are a powerful instrument in piercing the so-called blue wall of silence, the unwritten code among cops to not report a colleague’s misconduct. Smart phones can identify those officers who either observe or participate in killing but who remain utterly silent.

What is being tested in more and more states and cities is training police in how to gain control of implicit biases. Supported by former Attorney General Eric Holder’s 2014 initiative, the funding and content for this idea has been extended via President Obama’s “Task Force on 21st Century Policing,” which recommends “training for all levels of law enforcement to address implicit bias.”

RJ Matson, CagleCartoons.com

Los Angeles, Chicago, St. Louis, and Baltimore are applying different phases of the training. According to the May issue of Police Chief magazine, early results indicate that becoming aware of their own unconscious biases helps officers see situations for what they actually are rather than through the lens of their fears and stereotypes. The article, “Implicit Bias and Law Enforcement,” by Tracy G. Gove, is well researched and includes discussion of community policing. Like many other social and economic factors, community policing is beyond the scope of this article but its significance should not be minimized.

There are several remedies, however, that are pertinent and that I do wholeheartedly recommend. My suggestions come from sixty years as an inner-city social group worker, community center director, NGO executive, and as chair of the Lower East Side Call for Justice. In my professional or activist roles I’ve met with groups of police officers and precinct commanders, had extensive communications with departmental and legislative decision makers, and conducted seventeen years of training for youth of color on why and how to avoid being abused and how to avoid arrest. Most often a person of color was my co-leader and we conducted over 250 workshops on the Lower East Side, East Harlem, and the Upper West Side of Manhattan (the latter as referrals from The New York Society for Ethical Culture). We have letters of commendation from the program directors and have repeatedly been asked to return when new individuals and groups joined their programs.

These are my recommendations:

- Test the efficacy of body cameras on police;

- Extend training across the country on how to gain control of implicit biases, especially when a police officer thinks his or her life is in danger;

- Pierce the “blue wall of silence” by exerting appropriate discipline on officers who cover up killings by fellow officers;

- Urge and train people of color, men in particular, to cooperate with the police in street encounters. Teach them to become conscious of and in control of their implicit biases as well;

- Give commanding officers more power to discipline and dismiss officers who have proven to be unable to control their emotions during encounters on the street;

- Reduce police surveillance in poor neighborhoods when crime is down; and

- Promote the idea that protests need accountable leaders. Some of the recent protests (in New York City, Baltimore, Oakland, Berkeley, and Seattle) were well intentioned but were leaderless, lacked an insistence on nonviolence, and resulted in attacks on police officers.

In summing up, let’s face the fact that making life-and-death decisions in an instant during street encounters is among the most difficult things any human being can be called on to do. Let’s help citizens and law enforcement reduce those encounters and equip the police with the psychological tools to avoid taking another’s life when their own is not in imminent danger.