Book Excerpt: White Nights, Black Paradise

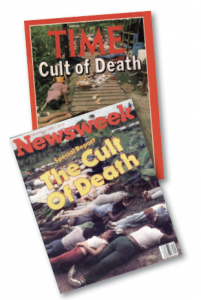

On November 18, 1978, over 900 members of the Peoples Temple, a multiracial church with Pentecostal origins, died in a Guyana jungle settlement named after the church’s white founder, the Reverend Jim Jones. On that fateful night, a U.S. congressman investigating the church was murdered, and Jonestown members either drank or were forcibly injected with a deadly combination of cyanide and Flavor-Aid. Seventy five percent of those who died in the Jonestown massacre—the largest murder-suicide in U.S. history—were African American. The majority of these victims were African-American women.

White Nights, Black Paradise (Infidel Books, 2015) focuses on three fictional black women who are part of the Peoples Temple movement but have taken radically different paths to Jonestown: Hy, a drifter and spiritual seeker; her sister Taryn, an atheist with an inside line on the church’s money trail; and Ida Lassiter, an activist whose watchdog journalism exposes the rot of corruption, sexual abuse, racism, and violence in the church, fueling its exodus to Guyana. White Nights, Black Paradise is a riveting story of complicity and resistance, loyalty and betrayal, black struggle and black sacrifice. It locates the Peoples Temple and Jonestown in the shadow of the civil rights movement, Black Power, second-wave feminism and the Second Great Migration. Recapturing black women’s voices, author Sikivu Hutchinson’s first novel explores their elusive quest for social justice, home, and utopia. In so doing, the novel provides a complex window into the epic flameout of a movement that was not only an indictment of religious faith but of American democracy.

Chapter 9

Ida Lassiter, Witness, 1963

THE LAST SUNDAY SERVICE brought out all the rubberneckers. The ones who thrilled at a car crash on the horizon, slowing down, salivating as they neared the blood, guts and gore. If they were going to get saved that week then 4 p.m. at Peoples Temple was their last chance. The church band and the choir were always crack, egging on audience members who’d gotten the spirit, accenting Jim’s pulpit exhortations about apocalypse with a horn blast, drum roll, or flute trill. Nuclear holocaust is a’coming, he screeched, and the only ones gonna get saved would be the Temple faithful.

This is what his visions told him, thrashing in his sleep with his thumb in his mouth and the night light on. The cowardice. The mama’s boy shipwrecked in his own head.

This is what his visions told him, thrashing in his sleep with his thumb in his mouth and the night light on. The cowardice. The mama’s boy shipwrecked in his own head.

I sat in the back pews and watched the afternoon’s last dance of surrender. The musicians were black, white, mulatto, shiny untapped talent from the train track neighborhoods and bedroom suburbs, some barely out of high school, some recent drop-outs hot with disillusion; a fierce junior league hungry for the next breakneck chapter in their parched lives.

Jim called on me every month at the office with some new scheme for collaboration. The hotel strike years ago had galvanized him, raising his local profile as an audacious nigger lover with a jackleg church and a silver tongue. I could see him growing out of his puppy-hood as he got more confident. I could see him smelling himself, reveling in his youth, his novelty, his supernatural recall of the most obscure face and tortured personal history.

At night, the glimmer of something in him tugged at me, under the leaden waves of dream, a lamprey attaching in my sleep.

Elders from the white Pentecostal congregations sought him out as a whiz kid who could talk CIA spying one minute and the healing power of prayer circles the next. Jim began to ham it up, adopting a southern cadence in his confessional sermons, dropping g’s, playing to the small throng of white women who hung on his every word and stayed after hours to clean up the church.

They were a grasping quintet which secretly jockeyed for dominance. Carol was the alpha who kept the assembly line of all the Temple’s programs moving. She and Mabelean criss-crossed each other warily, avoiding duplication, maintaining a strict division of labor. Carol played the enforcer, supervising church finance. Mabelean channeled the Virgin Mary; sweet talking, soothing, her honey dipped voice soaring over Jim’s during the hymnals.

The other white women, Sherie, Deb, the rest, monitored prospective converts. They tended to the curious who came for the faith healing, coordinating outreach letter campaigns to reel in ambivalent white seekers cockeyed about the Negro deacons hovering at the good Reverend’s side.

On weekends Jim plowed through our neighborhoods with his two little salt and pepper boys in tow. He dragged them to all the church picnics and summer ice cream socials, Easter egg hunts and autumn carnivals, talking integration and Moses beating back the Pharaoh.

“For example, just look at my little man Jimmy Jr. Top of his class and a genius in science and mathematics but them school board savages done barred him from the school his own brother goes to.”

Outraged, the women in my historical society took up a collection for Jimmy’s school supplies. More donations poured in after the feature story I ran in The Gazette. When it came to the beneficence of white folk some of us could out Tom Uncle Tom. Even the smallest, most perfunctory white gesture toward Negroes was deemed to be sympathetic. When they heard that Jim and Mabelean had been the first to adopt a Negro child in the state of Indiana they gushed with gratitude. These were the same ones who’d never lift a finger to help the boy’s mother before she had to give the child up for adoption; the same ones who railed about loose morals and those triflin’ country Negroes up from Tennessee spitting out babies in the slums. Forced sterilization should be provided at these clinics they go to for their birth control, one white-gloved Bethel Baptist steward told me. God bless that Jim Jones for doing what’s right and setting a Christian example.

A small groundswell of Negroes joining Peoples Temple started. Some came after Jim’s neighborhood canvassing. Some came after reading my articles on the church’s work. Some were inspired by the hot spring of ’58, when all the white homeowners’ associations in the area tried to run a black doctor out of his new house on Cranston Street, and Jim participated in a meeting I set up with the family and the mayor.

I had made it a habit to go to the church once a month when I wasn’t on deadline.

“When are you going to stay for an entire service?” he asked me one afternoon at the office.

“Sundays are work days, quiet time. This place shuts down and I can take advantage of a whole afternoon.”

He leaned forward in his chair, stretching his hands over the worn knees of his pants, a leg hitched up to reveal the hairy scruff of his leg, the fat calf thick from walking the city, from running up stairs to lay hands on bedridden prayer patients. Outside in the common area Harrison grunted his departure, sweeping up the mail imperially as he doffed the colorless hat, coat and gloves he wore regardless of whether it was thirty or one hundred degrees.

“I’ve lost the yen for listening to preachers. It’s tiring, dealing with intermediaries giving you their filtered version of the Lord’s word.”

“It’s not out of vanity that I want you to stay. I’d just like some advice on whether I’m giving my people enough.”

“Your people?”

“You think I’m being impertinent?”

“You sound like you want them on a leash.”

“I want all of them, everyone, to feel like they have a home with The Temple.”

“Home should be natural, not imposed.”

“Where do you get that impression from anything I’ve said or done? The church should be a provider and I’m doing that.”

“The way you said your father wasn’t?”

“What gives you the right to judge him?”

“Boy, you’ve only taken me into your confidence for the past decade now. There’s very little I don’t know about you.”

“I’m not a boy and I highly doubt I’m that much of an open book.”

“No? You lap at black people’s heels for approval and patronage. What kind of backbone is that showing?”

“Is that how you see me? As a lapdog?”

“No.”

“Then how? How do you see me?”

I paused. The building drained of life around us. What should have been an hour of release and contemplation was sullied by his grasping, desperate presence. I had a paragraph left on a story about the mayor’s latest capitulation to housing terrorists, then several hours of editing ahead of me, each wasted minute a squirming albatross on my neck.

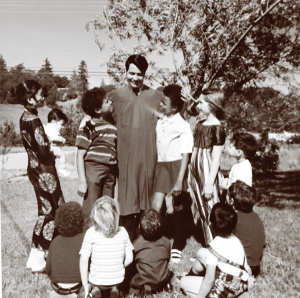

Jim Jones (Photo by Nancy Wong)

He twisted a hangnail off his thumb, rubbing the scab beneath. I pulled out a bandage from my desk drawer and handed it to him. He smoothed it on, feigning absorption as he awaited my verdict.

“I grind my teeth at night,” he said, “from the worry.”

“And what do you worry about Reverend?”

“About building this congregation, about doing right by the community. You think because I’m a white boy I wasn’t properly called—”

“I think no such thing. Let me see your thumb.”

He stretched out his hand bashfully, blood encrusted under the bandage.

“You’ll strip your fingers to the bone doing that. All that laying on of hands is giving you blisters. What is it that you think you’re doing with that voodoo superstition?”

“People have legitimate ailments that need to be cured if they can’t get to a doctor or aren’t rich enough to afford one.”

“You go to seminary for that? You have a degree in hoodoo-ology? A doctorate?” I lowered my voice. “You’re not a medical doctor, Jim. I know some of the effect is psychosomatic for folk. But the Lord will strike you down if you’re pulling a con on those people.”

“Oh will he?”

“Yes.”

“I’m a healer. I don’t pretend to have any special schooling or phony degrees. But what I will say is that there are men and women walking around right now who are cured of cancer, who can see, who are ambulatory for the first time in years because they went to The Temple.”

“All because of you?”

“Because of God working through me.”

“You don’t really believe that.”

He hesitated. “I do. I have to. How else do I build an alternative society and confront the endless war against working people and the Negro? Look at how they follow Dr. King. How they worship the ground he walks on. All because The Spirit moves in him, because he’s called, walks the righteous path for justice. Come see us this Sunday. Stay the whole time. We’ve got a boy in the choir, a foster child, He’s got a voice like an angel. Right out of the Sistine Chapel. S-say you’ll come.”

“I have deadlines and a paper to run.”

He got up from his chair and knelt down in front of me, running his fingers through his hair, black strands falling.

“Say you’ll come.”