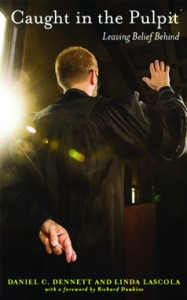

Caught in the Pulpit: Leaving Belief Behind

Doubting the divine while still wearing the seal of the cross can be psychological torture, like being held captive in a medieval dungeon of the mind. It is a place of loneliness, despair, and limited options—a place one can’t easily emerge from unscarred. (Full disclosure: I’m currently working on publishing a book based on my own ascension in the ranks of Christian ministry, life’s challenges, and my eventual reasoning into humanism.)

In Caught in the Pulpit: Leaving Belief Behind, researchers Daniel C. Dennett and Linda LaScola bring forth stories of current and former clergy who are, or were, serving the faithful while personally witnessing the twilight of their own belief. They interviewed thirty-five people over the course of three-and-a-half years, asking questions regarding the experience of being inspired by the supernatural, the internal process of questioning the faith, and participants’ personal choices to leave their religious community or to stay on at their post regardless of a theological shift. The interviews were conducted confidentially with those representing a variety of religious doctrines, including Pentecostalism, Presbyterianism, Mormonism, and Judaism.

Caught in the Pulpit tempts readers with these personal, sometimes tragic stories of those who have moved on from the pulpit or are still trapped there. I was originally drawn, as many of you might be, by the seemingly “controversial” nature of the material, the secrecy surrounding the interviewees, and a natural curiosity about the “good dirt” these people may spit out about their religious background. Though the book does provide anecdotes of perceived hypocrisy, cover-up, and scandal, this is first and foremost a research book, along with a depiction of what the writers see as the sanity of post-religious ideology.

The authors begin by describing what qualitative research is, its value, and its process, as a way to validate a lack of bias. They then share short testimonials with sometimes socially tragic details in an attempt to give us a window into the harsh reality of post-religious life. We get segments from people’s stories, including hints at confessions of sexual abuse and social discrimination to support the author’s findings. But as an individual who appreciates personal narrative, I felt stories were selectively truncated and good storytelling was, at times, sacrificed to focus on the research results.

Delving into that research, we learn about how troubled religious leaders felt in their process of doubt, what the breaking points were that made them part ways with their theology, depression they experienced, and how their community responded.

The book does a good job of describing three main phases in the spectrum of belief. First is the “literal,” which describes the more traditional and conservative segments of the religious population, who may be guided more by emotion and relationship, and who believe in the inerrancy and literal translations of the Bible. The “liberal” are those in the religious community who stand closer to the side of interpretation based on logic and intellect, and who believe the Bible to be more inspired than fully literal in its meaning. Third is the “nonbeliever,” who has either always been on or who has made a complete trip to the side of reason and away from religious belief.

While the book preaches to the choir of the “nonbelievers,” it also encourages the so-called liberals to continue the path all the way to full enlightenment.

In the real religious world, beyond literals and liberals, beyond any acceptance of what makes sense logically, there is the Christian’s relationship with Jesus Christ. For the faithful he is the first breath they take in the morning, the heartbeat of their loved ones, and the gravity that holds life in place. It is a relationship with an individual who is part of one’s dreams, the target of one’s expectations, the center of any conflict, possessor of one’s gifts, and the ultimate judge of his or her successes.

This is why, even though many people will admit there is truth in the theory of evolution while seeming to subscribe to a creationist worldview, they’ll still find it heartbreaking to consider parting ways with their best friend and most loyal companion. It may be worth it to endure such pain in order to keep what little of their lives is still in balance.

When I stood inside hundreds of churches to preach the value of Christian life and then went home to a fog of doubt, I wasn’t trembling because of a lack of sense in doctrine, but because of the lacerating possibility of divorce from a community. I was unable to bring my private shadows into public ears, but searched for sources of testimonies that sounded and looked the way I felt.

While facts and figures speak great lengths in the languages of the mind, a personal story hits at the heart of the reader who admits, “this feels, aches, sweats, and bleeds just like I do.” Religion can be broken down by research and findings. Relationships can only be processed by time, words, and actions.

If I were judging the target audience for Caught in the Pulpit, I’d probably place this book a little closer to the textbook section in the library. If you’re looking for a book on reactions, consequences, and short stories about what it feels like to depart from Judeo-Christian values, then you’ve found your book. It’s great for referencing and footnoting. More traditional readers, however, may find themselves lost in academic structure and thirsty for a full narrative that describes how they feel in real life.

In addition, this book is written for an older audience. It covers areas of financial security, marital situations, retirement, and other long-term consequences of choosing to leave one’s religious faith. Also worth noting is that while the book’s participants are diverse in religious background, gender, sexual orientation, and, to some degree, age, ethnic minorities are not represented. These groups would seem crucial in research like this because they very often experience a more cultural attachment to their faith. Though the authors may have had valid reasons for the omission, I couldn’t help being reminded of an old joke from the early days of psychological research: “even the lab rats are all white.”

For anyone who’s made it all the way to the end of their faith, this book will likely prove both validating and encouraging. If you’re a reader who appreciates academic research, you’ll find it informative and gratifying. If you’re a reader who is questioning a religious affiliation, you may find yourself responding with “I know what that feels like.” And if you’re a reader who is confident in a present belief in the supernatural, you may be challenged by honest stories of those who have been where you are and made tough choices in spite of tough consequences.

One thing is for sure, whatever “phase in faith” or point on the spectrum you may find yourself on, it’s important to remember the idea that opened this review: when it comes to faith, doubting can be a form of torture. If anything, this book will give you a better perspective, or a reminder, about how personal and difficult the choice of leaving belief behind can be. This is something about which we should always be very respectful and empathetic.