Out of Place A Boulder Church’s Path toward Denominational Realignment

Photo by Joey Getty

Photo by Joey Getty IN MARCH, the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), the largest Presbyterian denomination in the country with 1.8 million members, announced it would start allowing its ministers to preside over same-sex wedding ceremonies. While it certainly marks a sea change, the easing of rules concerning gay clergy and same-sex unions has been occurring within the PC (USA), as it’s called, for decades. Meanwhile, a new denomination is emerging throughout the nation—but instead of loosening the old chastity belt, it’s cinching it up. ECO: A Convent Order of Evangelical Presbyterians, has set up shop in more than 180 Presbyterian churches across the United States, including near the foothills and marijuana dispensaries of Boulder, Colorado, inside the First Presbyterian Church of Boulder.

Though it appears to be an acronym, the name ECO is part of the denomination’s full name and, according to their website, reinforces their “passion for strengthening the ecosystems of local churches.” Using a green design scheme and a cross-within-a-leaf logo, along with words like ECO, ecosystems, strengthening, and local, the denomination’s marketing jells very well with Boulder stereotypes. But why would First Presbyterian Boulder (commonly referred to as First Pres) separate from PC (USA) to start a new relationship with the younger, more starry-eyed ECO?

Most ECO churches cite financial constraints and theological discrepancies as reasons for leaving PC (USA). Admirably, ECO’s website lists “Egalitarian Ministry” as a core value (“We believe in unleashing the ministry gifts of women, men, and every ethnic group”), however a key policy difference between ECO and PC (USA) is the former’s shift back to disallowing gay marriage and noncelibate gay clergy. (Also included under ECO’s core values is the statement: We believe guidance is a corporate spiritual experience.)

Infer as you will, but ECO was officially founded in January 2012, about eight months after PC (USA) voted to green light the ordination of openly gay, noncelibate clergy. A month later, First Pres Boulder appointed a task force “in response to ongoing concerns about the health and direction of the PC (USA),” according to the church’s website discernment updates.

It had been more than a year since I’d set foot inside a place of worship. Yet, there I was on Sunday, February 8, 2015, walking into the 8 a.m. traditional communion service at First Pres Boulder. After circling the large building a few times, second-guessing myself on whether or not I had chosen the correct door, I found the service. It was a surprisingly charming little chapel room filled mostly with retirement-age individuals and couples.

I sat in the back row of cushioned pews. As I looked forward at the rows of balding heads and permed hair, I wondered whether any of these parishioners would be directly affected by First Pres Boulder’s denominational switch. Not to say that later-in-life homosexual love is unlikely, but I somehow doubted they’d waited decades for the PC (USA) to change its stance on homosexuality.

The only other people who appeared to be in my 20-35 age group were part of the service, speaking on behalf of “bright-eyed and bushy-tailed” recently married couples. A few teenagers were perched atop a balcony running a basic A/V system, which projected song lyrics and the occasional quote.

Humbled by the chapel and its kind-eyed, aging congregation, I was caught off guard when I entered the 11 a.m. contemporary service.

The quaint chapel was empty. I was a few minutes early, but I knew I was in the wrong place. After meandering through a series of small doorways, I found a Christian book shop and a gathering of families that looked ready for church. Beyond were several sets of doors that I had anticipated would lead to a larger version of the chapel.

Photo by Joey Getty

FIRST PRESS BOULDER calls it “the Sanctuary.” It’s an epic space, vast enough to fit a handful of chapels within its walls. Stained glass windows behind a giant cross cast a hazy blue light down the center of the pews. Where the chapel had a traditional altar with an organist playing behind the pastor, the Sanctuary had a full stage equipped with amplifiers, electric guitars, a drum set, and microphones on stands. At this point, I wouldn’t have been surprised if someone told me the service was regularly televised.

This particular 11 a.m. service, similar in basic structure to the 8 a.m., was the final chapter in a four-part series of Sunday services that revolved around the ideas of marriage, sex, and divorce. While I unfortunately missed the “sex” service, this worship wrapped up the series by looping back to reflect on marriage, specifically the vows within the religious ceremony.

I sat near the front of the room on the end of a peripheral set of pews. A friendly family sat next to me. I chatted with the father about religious upbringings as we waited for the service to begin.

By the looks of the Sanctuary, this experience was going to be very different than the one in the chapel. For about five minutes, a Christian rock band played on stage. A few churchgoers raised their hands to reach up to the sky, appearing to feel or channel some sort of grace. I didn’t feel anything, but I also rather disliked the music. Then, a member of the church and leader of a moms’ group greeted the audience with a few announcements.

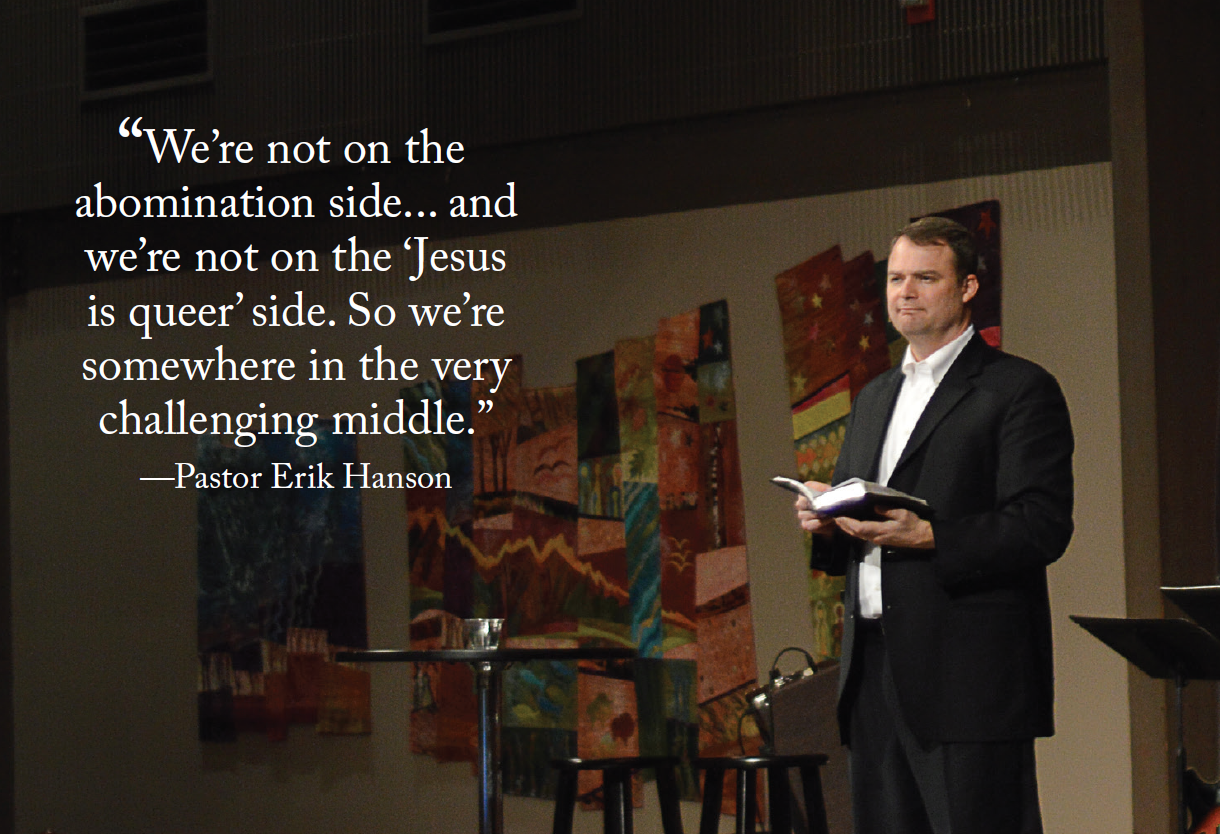

Just as I started to wonder whether Lead Pastor Erik Hanson would even make an appearance at this service, he popped up from a front pew, but instead of the traditional robes he adorned in the chapel, he was all business in a black suit and white button-down shirt.

Maybe it was because this service was considerably larger than the earlier one, but the pastor seemed to raise his voice more as he spoke to the crowd. He began with a reading from the “Statement on the Gift of Marriage,” from the Presbyterian Book of Common Worship, which includes the line: “God established marriage for a woman and a man…”

After a performance from a middle school choir, Pastor Hanson asked a young boy to read the traditional marriage vows. He then remarked, “Folks, those vows are easy enough to be read by a very nervous fourth grader.”

Standing center stage, Hanson began to look more and more like a motivational speaker. The large, well-lit stage allowed him to move back and forth as he alternated his gaze from one end of the Sanctuary to the other.

Besides the more showy performances by the band and the pastor, the content of the service was interesting. Three testimonies to marriage were given by the aforementioned bushy-tailed newly-ish married couple; a middle-aged, down-to-earth couple; and, finally, an older gentleman who struggled for several years married to a woman with dementia.

The messages of these testimonies resonated with me, as I have put a good deal of thought into popping the question to my girlfriend of three years. Then again, I am in a nonreligious heterosexual relationship—not someone of faith who is in danger of having his or her equality denied. For this church, a denominational change to ECO would take religious gay marriage off the table. I began to wonder more about the lead pastor’s beliefs as well as his thoughts on First Pres Boulder’s discernment.

PASTOR ERIK, as many of his parishioners call him, came to First Presbyterian Church of Boulder from Berkeley, California, in 2012. In about two and a half years, he has built a positive rapport with many church staff members. While I waited to speak with him, his administrative assistant listed off his many attributes, as well as her positive experiences working as an intern at First Pres Boulder.

The room Pastor Erik and I met in had a couple of small stained glass windows, but no traditional desk. Instead, there was a seating area with a table and three chairs set up near a large bookcase. I sat down in one of the comfortable chairs.

On the surface, Pastor Erik appeared to be a kind-hearted, quirky man. He had a kind of catch phrase that he repeated during the interview: “Uh-huh-uh,” which to me signified a “yes and no,” or “more or less” response.

First, I was interested in hearing about his role in seeking dismissal from the PC (USA). He noted that the church’s Compass Task Force, which had started to feel out the congregation’s support of dismissal, was formed some six months before he arrived at First Presbyterian Boulder. “And what I said to the entire church, on the Sunday when I was elected to be the church pastor, was that I just didn’t want it to be my legacy here,” he told me. “It’s not my thing. I didn’t come here to lead a church out of a denomination.”

Photo by Joey Getty

Photo by Joey Getty

When we started to talk about the potential to affiliate with ECO, he seemed fairly enthusiastic, but he had a few reservations. “We don’t know how this is going to play out. There will be a financial settlement with our Presbytery,” he noted.

That financial settlement would result from the fact that the Presbytery of Plains and Peaks holds First Presbyterian Boulder’s church property in trust—one of the reasons the church seeks dismissal. Property ownership is one of five areas “of central concern” described in a collection of documents located on First Pres Boulder’s website.

Pastor Erik told me about some of the problems associated with the PC (USA)’s “Trust Clause.” “People are unwilling to give for capital expenses when we don’t actually own the investment afterwards,” he said.

The disagreement over human sexuality is noted in the same document under a “theological identity” concern. However, in a section describing summary statements, the eighteenth conviction states, “Yes, the PC (USA)’s understanding of human sexuality is evolving, but our study and discernment has not led Session to make this a primary reason for seeking dismissal.”

I asked Pastor Erik to elaborate on this point, as I attempted to understand how major of a factor the debate over human sexuality was for him as well as how he perceived his congregation’s position.

“We are essentially a theologically and historically orthodox church. What that means for us is, you know, we might be branded by others as theologically conservative,” he told me, adding, “Some people are going to be absolutely convinced that this really is just a gay thing…and that really is not at the heart of what we talked about. At all.”

He began to describe how the diversity of opinion on homosexuality within the PC (USA) does not help a group of people worship together. “I think what we’re saying is, ‘Hey, we’re not over here. We’re not on the abomination side,’” he said, referring to those on the far right of theological beliefs on homosexuality. “And we’re not on the ‘Jesus is queer’ side. So we’re somewhere in the very challenging middle.”

Then I asked a hypothetical question: “If there were a third option that was theoretically identical to ECO, but allowed for ordination of actively gay clergy and gay marriage, do you think that would be a better option for First Pres?”

He responded, “I think probably not at the moment.” He didn’t want to add anything to that statement.

Later in the interview, Pastor Erik said that neither he nor other First Pres pastors had presided over a religious same-sex marriage ceremony during the church’s discernment process. “I also haven’t been asked,” he noted, adding, “I don’t think that I would, honestly.”

In terms of how a run-of-the-mill First Pres churchgoer would know about the difference in policy between ECO and PC (USA), Pastor Erik said that while the information has been widely available online and during numerous meetings, church leaders had not discussed these topics during any of the Sunday services.

“The way I understand it, denomination is important infrastructure, right? But also, it’s important infrastructure or scaffolding or foundational work that you really shouldn’t think about, or talk a lot about because it’s not the primary thing that we are worried about,” he said. “For the last thirty years, there have certainly been these slivers of moments—we’re in one of those right now—where we have had to talk about our denominationalism. But it should be hidden, not out in front.”

Throughout the First Pres Boulder’s online documentation of the discernment process, as well as during my interview with Pastor Erik, the timespan “for the last thirty years” or “for the past few decades” was repeated, signifying the time since the merger of the Presbyterian Church in the United States and the United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America to form the PC (USA). In many situations, ECO churches and aspiring ECO churches use the “decades-long struggle” preface to assert how their decision to split is not primarily based on the PC (USA)’s very recent changes in stance on homosexuality within the church.

On whether or not Pastor Erik would ever preside over a same-sex marriage ceremony or condone the ordination of an openly gay pastor, he said, “I think as a Christian, I always have to be open to the possibility…of having my heart and mind changed as I seek to read and study scripture and live in a complicated community.”

He paused for a moment and added, “But…I don’t see that coming any time soon.”

In terms of how a denominational switch to ECO would affect his personal financial situation, Pastor Erik pointed out that individual Presbyterian churches are in charge of a pastor’s salary, while the national denomination covers pension and benefits. As such, he could incur a loss of financial security. “In the PC (USA), the pension and the benefits that come with being a pastor are really generous. And ECO is probably not going to be able to match them,” he said.

Toward the end of our interview, Pastor Erik asked me about my angle. I told him the denominational change to ECO seemed to be out of place for Boulder, which in 1975 was one of the first cities in the United States to issue same-sex marriage licenses.

He told me he was disappointed. “Let me just be really clear with you. That’s not the story. This is not about homosexuality,” he said.

I clarified that I was not intending to prove that the debate over homosexuality was the reason for First Pres Boulder seeking dismissal from the PC (USA). Instead, I explained that I viewed the potential major outcome of First Pres’s alignment with ECO as revoking a newly bestowed right to same-sex couples and gay pastors.

“There are already lots of downtown churches that already do those things you’ve talked about,” he responded, somewhat defensively. “So…great. Go there.”

ON MARCH 1, First Pres Boulder congregation attendees had the opportunity to partake in an advisory vote on seeking dismissal from PC (USA). (The vote was originally scheduled to take place on February 22, but due to bad weather and the questionable resulting attendance, it was rescheduled.)

Even though the advisory vote is not a deciding factor in the dismissal process, the Presbytery of Plains and Peaks will take it into account as they analyze whether First Pres Boulder is a potentially viable PC (USA) church moving forward. According to Pastor Erik, the Presbytery is likely to vote in October, though he said that it could be earlier or later.

I attempted to speak with members of the Administrative Commission of the Presbytery of Plains and Peaks, who were administering the vote at the March 1 gathering. They declined to comment on the dismissal process.

Nevertheless, the overwhelming confidence of Pastor Erik, as well as that of First Pres’s Associate Pastor for Spiritual Formation and Discipleship, Dr. Carl Hofmann, led me to believe the result of the vote would be a large majority in favor of dismissal. On March 6 their predictions came true—the Presbytery of Plains and Peaks released the landslide advisory vote results, showing that nearly 87 percent of voters were in favor of dismissal.

I ATTENDED the 9:30 a.m. service on the day of the advisory vote to see how it compared to the 8 a.m. and 11 a.m. services. Located in the Sanctuary, this middle service incorporated a more traditional altar with an adult choir. Pastor Erik wore his suit, this time with a tie.

After the service concluded, I explored another area of the building, the atrium, where many parishioners gathered. On the walls of the atrium hung a “Faces of Freedom” exhibit that depicted portraits and stories of human trafficking survivors.

Here, I was reminded of the many ways First Pres Boulder reaches out to the local and global community in order to raise awareness for good causes and improve the lives of struggling individuals and families. During my interview with Pastor Erik, he stated that he believed First Pres would be less distracted from its good deeds if it were no longer affiliated with the PC (USA).

At the end of my visit, I was left with a few lingering questions about the future of this church as well as the future of the ECO denomination.

If a church in one of the most politically liberal cities in Colorado realigns with the notably more conservative ECO denomination, what does that say about the theological direction of Christianity in the United States? While the PC (USA)’s recent changes have reflected the growing acceptance of same-sex marriage in state politics, why is it that some religious individuals say “okay” to legality, but at the same time, “not in my church”?

And, perhaps the toughest question of all: If First Pres actually does more good within the community under the ECO denomination, is it worth the reinstated discrimination against same-sex congregants and actively gay clergy?