Biblical Scholarship and the Right to Know

Biblical scholar, author, and former born-again Christian Bart Ehrman is recognized as a preeminent expert in the field of biblical criticism. He has authored over twenty books on subjects ranging from theodicy and the problem of evil, to the history and composition of the New Testament, to books about early Christianity geared toward the general public. His books Misquoting Jesus, God’s Problem, and Jesus, Interrupted were all critically acclaimed New York Times bestsellers. His latest book, Forged, is a careful examination of the New Testament gospels that calls into question the “official story” of the Bible’s authorship. Ehrman has been published in the New Yorker, the Washington Post, and many other top publications, and his media appearances include CNN, BBC, the Colbert Report, the Daily Show, and NPR’s Fresh Air. Ehrman was presented with the Religious Liberty Award at the American Humanist Association’s 70th annual conference in Boston, Massachusetts, not just for outstanding scholarship in the field of biblical criticism, but for publicly advocating honesty about the biblical record and the history of early Christianity. The following article was adapted from his speech.

I’m honored to be the recipient of this award, and I’d like to offer the association my sincerest thanks.

This is a very different audience from what I’m accustomed to as a scholar of the Bible. I teach in the Bible belt, and my students come largely from North Carolina, have grown up in the church, and, in my experience, have a much deeper commitment to the Bible than knowledge about it. So when I teach my class in the New Testament, which I do every spring semester, I begin by explaining that it’s not a Sunday school class and I’m not a preacher. I’m a historian and the class will engage in a historical study of the New Testament.

I then give students a pop quiz, which they think is very odd since I haven’t taught them anything yet. But I want to know what they know about the Bible. And actually I want them to know what they know about the Bible. It’s not a hard quiz; there are eleven questions and I tell them that if anyone gets eight of these eleven right, I’ll buy them dinner. Last year, out of 300 students, I bought one dinner.

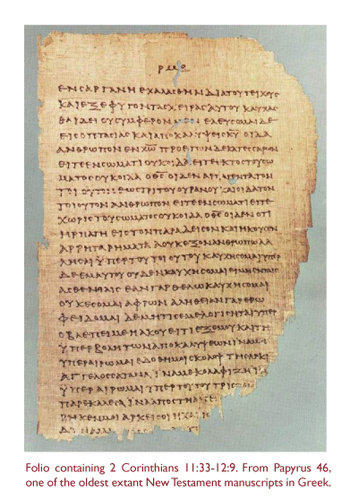

Like I said, they’re not hard questions and these are mostly conservative, Bible-reading church kids. The first question is: How many books are in the New Testament? (It’s actually a very easy answer: twenty-seven. Because you think about the New Testament, you think God. You think the Trinity, and what is twenty-seven? It’s three to the third power. It’s a miracle!) The next question is: What language were these books written in? Now, it’s interesting––half of the students think the answer is Hebrew, which is wrong. Fortunately, only about four or five students typically think the answer is English. It turns out the answer is Greek. Greek was the lingua franca of the Roman Empire, just like English is the common language today.

One of the reasons I give this quiz is to get the students to start learning some things. And one of the things I want them to learn right off the bat is that the contention that the very words of the Bible are divinely inspired has some problems. First, the Bible wasn’t written in English, it was written in Greek. So when you’re reading it in English, you’re reading it in translation. Not only that, but Jesus spoke Aramaic. And there are some things in Aramaic that can’t be represented in Greek, and then there are things in Greek you can’t represent in English. You’re getting it third hand and things get changed with translations, so it ends up mattering.

I also throw in some curve balls (after all, I can only buy so many dinners). One of these questions is: What was the Apostle Paul’s last name? Often enough somebody will answer, “of Tarsus.” But part of the point is that people in the ancient world didn’t have last names unless they were in the upper crust of the Roman aristocracy, where people had multiple names. If you were a normal person, you’d just have one name. And that’s why in the New Testament, when many people have the same name, they use identifiers. Mary is an example; in the New Testament you have Mary the mother of Jesus, Mary of Bethany, Mary Magdalene, and so on. This is news to my students, some of whom naturally think that Jesus Christ was born to Joseph and Mary Christ.

I also throw in some curve balls (after all, I can only buy so many dinners). One of these questions is: What was the Apostle Paul’s last name? Often enough somebody will answer, “of Tarsus.” But part of the point is that people in the ancient world didn’t have last names unless they were in the upper crust of the Roman aristocracy, where people had multiple names. If you were a normal person, you’d just have one name. And that’s why in the New Testament, when many people have the same name, they use identifiers. Mary is an example; in the New Testament you have Mary the mother of Jesus, Mary of Bethany, Mary Magdalene, and so on. This is news to my students, some of whom naturally think that Jesus Christ was born to Joseph and Mary Christ.

The other crowd I typically speak to are conservative evangelical Christians, as I’m frequently invited to do public debates with academics from their ranks. This spring, for example, I debated an evangelical Christian scholar named Craig Evans on whether the gospels of the New Testament are historically reliable. This was at the New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary in front of 700 people. Two of them were on my side. Three months earlier, I debated Dinesh D’Souza at Gordon College, a conservative evangelical school in Massachusetts. Six hundred people were in attendance, three of whom were on my side. And so it goes.

I should add that I am always well received in these contexts. Even so, every time I do one of these debates and my opponent is talking and everybody’s applauding, I’m writing notes to myself asking, why are you doing this? During those moments of darkness, I comfort myself by reasoning that at least I’m trying to get people to think, whether they’re religious people or not. This is one of my goals as a scholar, to get people to think—to question what they believe, so that they can liberate themselves from whatever forms of ideology or religion may be preventing them from living life to the fullest and from showing love and concern for the wellbeing of others.

Let me also stress that I’m not opposed to religion and I don’t think that all religion is oppressive—far from it. I also think that people should be free to embrace whatever religious or non-religious views they choose whether they’re Christian, Jewish, Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim, Pagan, agnostic, humanist, or atheist, so long as they don’t use their religious or non-religious views to silence, oppress, or harm others. Even though I’m not opposed to religion, I am opposed to strident ideology and to every kind of fundamentalism.

I myself was a fundamentalist, and it took me a long time to be over it. When I was seventeen I attended the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago, a bastion of fundamentalism where my fellow students and I believed that the Bible was inerrant in everything it said. There were no mistakes in the Bible of any kind. This is what we were taught and this is what we believed.

As far as internal contradictions in the Bible, we could reconcile anything at the Moody Bible Institute, and we did. The fact that there are two accounts of creation in Genesis that are completely at odds with each other? No problem. The fact that the Gospel of Mark says Jesus cleansed the temple as the final act of his public ministry before being arrested, whereas in the Gospel of John, he did it at the very beginning of his ministry three years earlier? No problem. He did it twice, beginning and end. Sometimes the reconciliations got a bit ridiculous. Jesus tells Peter that he’s going to deny him three times before the cock crows according to the Gospel of Matthew. According to the Gospel of Mark, he says, “You’ll deny me three times before the cock crows twice.” Well, which is it, before the cock crows or before the cock crows twice? Easy solution: Peter denied Jesus six times—three times before the cock crowed, and three more times before the cock crowed twice.

Once I graduated from Moody Bible Institute, I went to Wheaton College and there I learned Greek because I wanted to learn how to read the New Testament in the original language. And it turned out that I was good at Greek and good enough that I wanted to go on and do a PhD, working in the Greek manuscripts in the New Testament. And so I went to Princeton Theological Seminary because there was a great scholar of the Bible there, a man named Bruce Metzger, whom I still revere to this day. (He died several years ago.) But once I started reading the New Testament in Greek, I started finding problems. And what’s interesting to me now looking back is that I could deal with the big problems, the conflicts with science and other big contradictions. What ended up getting me were those little problems, the details.

I remember taking a class on the Gospel of Mark and trying, in my term paper, to reconcile one of its famous little inconsistencies. It’s this: According to Mark chapter two, disciples of Jesus are walking through the fields eating grain because they’re hungry, and opponents of Jesus are angry about this because it’s the Sabbath, and eating on this day is prohibited by Jewish law. In response, Jesus asks if they remember what David did when Abiathar was the high priest, how he went into the temple and ate the shewbread that only the priests are supposed to eat. It’s a fairly straightforward passage. The problem is when you look up the reference to King David doing this in the book of Second Samuel, it wasn’t Abiathar who was the high priest, but rather Achimelech. Now, who really cares? Fundamentalists care.

And so I wrote a thirty-five-page term paper arguing, on the basis of the Greek grammar, that even though Mark said that Abiathar was the high priest, he didn’t mean that Abiathar was the high priest. What he really meant was that Ahimelech was the high priest. Thirty-five pages was a lot of work, and my professor gave me an A on this paper. But at the bottom of the last page, he wrote a little note that said, “Maybe Mark made a mistake.” That would certainly have been easier, of course then I wouldn’t have had a thirty-five-page term paper.

Other little details became chinks in my fundamentalist armor. Did Jesus die the day before the Passover meal was eaten as he did in the Gospel of John, or the day after the Passover meal was eaten as he did in the Gospel of Mark? To me these were quite different and couldn’t be reconciled.

At some point seeing the small differences opened me up to seeing big differences. The Gospel of Matthew, for example, insists that the followers of Jesus had to keep the Jewish Law, but Paul says they were not to keep the Jewish Law. It’s a big difference between a major teaching of Paul and a major teaching of Matthew. Also, throughout the Gospel of John, Jesus called himself divine. He was God. He didn’t say that in Matthew, Mark, or in Luke. Now, if the historical Jesus really went around saying that he was God, don’t you think the Gospel writers might mention it, that this would be considered something worth knowing? In fact, the earlier Gospels don’t record this because Jesus didn’t say it about himself.

I eventually had to leave the fundamentalist fold and the conservative evangelical fold. And then for a long time I was a liberal Christian.

I ended up leaving Christianity and becoming an agnostic not because of my scholarship but because I simply couldn’t understand how there could be a good and powerful God who’s in control of this world given all the pain and misery in it. We live in a world in which a child starves to death every five seconds, a world where almost 300 people die every hour of malaria. We live in a world ravaged by earthquakes and tsunamis and hurricanes and drought and famine and epidemics, and I just got to a point where my previous solutions no longer made sense.

Now that I’m not a Christian in any sense, I see that my religious past, especially my fundamentalist past, was oppressive and harmful. I now think that it kept me at that time from being fully human, and it was used as a means of control. As a result, I’m no longer a believer who studies the Bible. I’m a historian who studies the Bible, and I study it because I think it’s so important for understanding our history and culture, and I think that as a scholar of the Bible, I can help other people who are also oppressed by religion. I try to make my research useful to others by making public what scholars have long been saying about the Bible. Most of my popular books that fundamentalists have found so offensive are books in which I simply lay out what scholars, even Christian scholars, have been saying for centuries.

My view is that most fundamentalists migrate away from fundamentalism slowly over time based on tiny doubts that seep into their consciousness. One of my jobs as a public scholar is to find chinks in the armor—to show why the internally coherent system of religiosity people have is, in fact, flawed. That involves talking about discrepancies in the Bible, its contradictions and historical impossibilities, as well as talking about the problem of suffering, and so forth. I do this because I think it’s important to consider and confront the deep philosophical issues without settling for easy answers. I’m actually not interested in making everybody either an agnostic or an atheist. I am interested in getting people to think and become more intelligent about their views of the world, whatever their views are. And I’m interested in seeing people reject religion that is harmful and oppressive.

Being an intelligent believer means understanding the truth about the religion that one believes in, where it came from, how it became what it is, and the historical and cultural forces that molded it. As a biblical scholar, I’m especially concerned with highlighting the truth about the Bible, and I think everybody has the right to know which of its views can’t be squared with the findings of science. People have the right to know that we don’t have the original writings of the New Testament but only later copies, all of which have mistakes in them. People have the right to know that there are discrepancies in the Bible, both major and minor, scattered throughout the entire thing, Old Testament and New Testament. People have the right to know that the historical Jesus appears to have predicted that the end of history as we know it was going to occur in his own generation. People have the right to know that many of the stories about Jesus in the New Testament were fabricated by well meaning but misguided Christians who wanted others to believe in him. People have a right to know that a large number of the twenty-seven books of the New Testament, as many as eleven or twelve of them, were not written by their alleged authors, the Apostles, but are in fact forgeries written by other people lying about their identity in order to deceive others.

These aren’t the wild claims of a particularly liberal agnostic scholar who teaches at Chapel Hill. They are that, but they’re also the findings of historians and are supported by critical scholars of most tribes—Christian, Jewish, agnostic, and so forth. And if these findings do put chinks in the armor of faith, what happens to those who leave it behind? This for me is a genuine question that I continue to struggle with, and I also think it’s where humanist and like-minded organizations come into play.

In my part of the world, in the South, humanists are largely known as negative opponents of all things religious, strident protesters against values that people in my world hold near and dear. So forgive me if I’m being overly obvious, but in my opinion, for humanism to strive and to succeed in these places, it’s not enough to protest. Humanism must make a positive impact on people’s lives and be looked upon, even by outsiders, as a good and healthy phenomenon. Among other things, humanists need to provide social outlets that mirror what believers have in their churches. When someone leaves the womb of the church, they need to have somewhere else to go. They need warm, loving, welcoming, safe communities of like-minded people where they can establish social networks and find fellowship with people who share their world views, their loves, hates, concerns, passions, and obsessions. They need context within which they can discuss the big issues of life, not just politics but also life-and-death issues. They need places where they can celebrate what is good in life and where they can work to overcome what is bad.

Humanist organizations need to become as recognizable as the Baptist church on the corner and the Episcopal church up the street. They need to be seen as the first responders when an earthquake hits Haiti, to be seen as major forces in the fight against poverty, homelessness, malaria, AIDS, and other epidemics. They need to be seen as vibrant and viable alternatives to the religions of the world, which often do so much harm while trying to do good. Whatever else we might say about organized religion, it cannot be denied that it is often the catalyst for much of what is good in the world. But it shouldn’t be the only catalyst, especially since so many people are silenced, oppressed, and harmed by religion. In other words, people must be liberated not only from something but also for something. That, in my opinion, should be the leading goal and objective of every humanist organization.

Once again, let me thank you very sincerely for honoring me with the Religious Liberty award.