Silver Lining in the Big Tent What a Humanist Future Can Mean

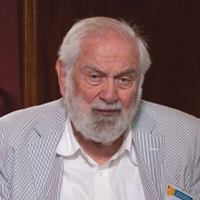

Carl Coon graduated from Harvard University in 1949 and promptly joined the U.S. Foreign Service. He spent the next thirty-seven years in a variety of posts stretching from Morocco to Nepal, serving as ambassador to Nepal from 1981-1984. After retiring in 1985 he began to write about the evolution of human society based on his anthropological experience and interest in evolutionary psychology. In his books, Culture Wars and the Global Village (2000) and One Planet, One People: Beyond “Us versus Them” (2004), Coon advocates the idea that the whole world must now be viewed as “us” to cope with current global challenges. In 2004 Coon was elected to the American Humanist Association Board of Directors and soon after became the vice president, a position he held for five years. Carl Coon was honored by the AHA with the Lifetime Achievement Award at its 72nd Annual Conference held this year in San Diego, California. The following is adapted from his acceptance speech given on June 1, 2013.

Back when I first became associated with the American Humanist Association (AHA), we humanists were pariahs. I remember that at one of the first conferences I attended, a couple of us got on an elevator with several young ladies associated with some other group. One of them looked at my nametag and asked, “What’s a humanist?” My friend replied, “We don’t believe in God.” The girls were shocked, frozen in horror and disbelief; they fled at the first opportunity.

We’ve come a long way. We still sit pretty far below the salt, but at least we now have a place at the table. It’s true that in the last couple of decades mainstream opinion has become more tolerant, more inclusive. Hispanics, LGBT groups, and other minorities have been battering down doors and we have benefited. Meanwhile, articulate atheists led by our friend Richard Dawkins have led an effective cavalry charge exposing the more ridiculous claims of the true believers.

But it’s also true that a favorable wind doesn’t do you much good unless you take advantage of it. I give former AHA President David Niose full marks for pushing through his idea of an advertising campaign, and persuading a rather reluctant board to take the plunge. That broke the mold in more ways than one. It started a sea change in public attitudes. Equally important, it persuaded us inside the movement that it was time to shift gears. Arguing about separation of church and state was fine but it was no longer enough. It was time to start fighting on a much broader front. AHA Executive Director Roy Speckhardt recruited a great team of young, gung-ho individuals, applied energy and creativity to what had been a pretty sleepy organization, and here we are today.

I’m struck not only by the scale of the effort, but by the diversity of approaches. This group seems to have sniffed out openings and opportunities to get our message across that would never have occurred to me. It’s impressive. But it’s not enough.

I’m struck not only by the scale of the effort, but by the diversity of approaches. This group seems to have sniffed out openings and opportunities to get our message across that would never have occurred to me. It’s impressive. But it’s not enough.

I guess I’m one of those people who’s never satisfied with success. I look at the AHA as it exists today and think, great! We’ve hit our stride, cruising altitude and all that, but now where are we going? It’s like what you ask some friend’s kid if you want to embarrass him, “What do you want to be when you grow up?”

What is humanism’s role going to be when it grows up? I believe the AHA needs to raise its sights and redefine its vision for our humanist movement. That vision should be nothing less than encouraging mainstream America to identify as a humanist nation.

Won’t it be great when our money is inscribed with the motto E Pluribus Unum instead of “In God We Trust”? And to know that our country has agreed to this and similar changes in our national symbolism, not just because some judge has ordered it, but because the great majority of Americans think the change is just plain right?

It may take a couple of generations, but our grandchildren, or at least their children, should be able to look back on a past when we considered ourselves a “Christian nation” and think, “Well, we’ve come a long way, haven’t we?” (Sort of like I felt when I first learned of our ancestral practice of burning witches in Massachusetts.)

Impossible? Nothing is, these days. Improbable? Perhaps. It would have sounded pretty unlikely if someone had predicted back when Barack Obama was thirteen years old that one day he’d be the president of the United States. But it happened. The old pols didn’t notice it much at the time, but the political climate was changing.

The political climate is still changing. The old coalition of forces that insists on defining us as a “Christian nation” is cracking up. Many fundamentalists are hanging firm, but judging from what Tom Krattenmaker writes about in his latest book, The Evangelicals You Don’t Know, the evangelical movement is fraying around the edges. Meanwhile, the changes may look agonizingly slow from where we sit but they are unstoppable. It’s like a glacier receding when the climate warms up. And actually, climate change is one of the forces causing this massive change in attitudes. Or it will be, when its effects become more obvious.

There is simply too much going on these days to let people keep on believing in the old revealed truths. Take the biblical origin myth, the Garden of Eden and all that. We have a better narrative of human origins now, and it isn’t a myth, it’s based on factual evidence. Our friend Richard Leakey (recipient of the 2013 Isaac Asimov Science Award) is a pioneer in the growing throng of paleoanthropologists who have made this narrative not only possible but plausible.

More generally, we have instant access to multitudes of information these days, so it’s harder than ever before to remain ignorant. I would guess that a majority of the Americans who still identify themselves as Christians either already share our science-based views, or are suffering cognitive dissonance. They constitute the political and cultural center of our country and, as I said, they are moving our way.

I need to introduce a caveat here. I don’t see almost everyone converting to humanism as an explicit kind of faith, the way almost all Arabs converted to Islam upwards of fifteen hundred years ago. But I can envision a fairly rapid evolution toward acceptance of the core values of humanism as we know it. As this evolution progresses, humanism can become a desirable label people and organizations use as part of the way they identify themselves. Mainstream opinion in our society can become humanist in fact if not in theory, and who knows, goodies like E pluribus unum can fall into place as a matter of course.

The AHA, in my opinion, is well placed to facilitate and encourage such a trend—and guide it. It follows that our best long-term strategy should be two-pronged. On the one hand we want to strengthen the organization itself, as measured by such criteria as membership and funding. But the other main task is to get broader public acceptance of “humanism” as the term of choice to describe the values we all share.

We need to broadcast the message that humanism isn’t just about denying God, it’s about a whole host of positive things about the environment, and our relations with each other, and about reason and science, and how we educate our kids—areas where most Americans already agree with us.

I recognize this is already an integral part of the AHA’s strategy. It’s what a good bit of the content of our ad campaigns is about, and what Jennifer Bardi is doing with the Humanist. But I can’t stress its importance too much. Expanding our image beyond the old one of a single-issue organization is the key to becoming a major player in the current ideological sweepstakes.

To the extent we succeed, we establish a kind of ideological common ground, a space where many diverse interests can get together and talk to each other. Humanism becomes a bond that unites all progressive Americans. (I would add that it also solves an emerging problem with the Christian nation concept, namely that more and more Americans aren’t Christians by origin, since they come from other faith traditions.)

We should look for coalitions at least as much as we seek conversions. Yes, we want our membership to grow, but it is at least as important that tens of millions of Americans come to think of humanism as something compatible with their own belief systems, as it is that tens of thousands sign up as AHA members. I suppose most of the mass movements of the past have had to choose, at one time or another, between ideological purity and the big tent approach. The ones obsessed with doctrine tend to break up over doctrinal disputes. We don’t need that. I’m all for pluralism and the big tent.

So let us think big, and set our sights on the larger goal of a revolution in how our nation identifies itself. But that leads to a second issue, timing. How urgent is the task ahead? How hard do we need to push? After all, most of the factors working for us exist whether we push the process along or not. Some sort of social and ideological evolution is likely to happen anyway over the next century. You might argue that it would be best to let our society evolve naturally, rather than force the pace, and risk bruising confrontations with the religious right.

But we may not have as much time as we’d like. The first tremors of climate change are already being felt. Political instability, compounded by population pressures, prevails in many countries around the world that used to be stable. (Where we used to talk about nation building, now we’re increasingly concerned with failed states.) We don’t know whether we can control chemical weapons or keep nuclear weapons bottled up.

You’d have to be an even greater optimist than I am to see the planet’s future in a rosy glow. On the contrary, we can look forward to an increasing cascade of really bad news. I suggest, that as the world increasingly shows signs of going to hell in a handbasket, we humanists talk to our neighbors, especially the ones that are religious with doubts. Ask them, what do you want to do about all these crises? Do you just want to pray for divine intervention, or would you rather get together with people like us who believe that our fate is in our own hands, and that we can and must adapt?

The looming disasters we face may range from the serious to the catastrophic, but there’s a silver lining in that they will get people to think more seriously about teaming up with us in that big tent.

And there’s another development, a big one, that can work in our favor, and that is the information revolution. For the first time in the history and prehistory of our species, every individual everywhere has or can soon have access to everything there is to know. The scientists tell us that each of our brains has billions of neurons blinking back and forth at each other, and that activity produces what we call consciousness. Maybe when a billion or more people start tweeting and twittering at each other something like a global consciousness will form that will help steer us into more adaptive behaviors.

That last may be a mite speculative. Let’s just consider it more poetry than science. But one thing is certain: the current information revolution in all its aspects presents the AHA with a broad set of options for spreading awareness of the humanist worldview. I know the whole AHA team is already onto this, and I wish them well.

But let’s not underestimate the importance of the job that lies ahead. It goes beyond making AHA bigger and stronger. Our country is in trouble. It’s like a snake that has outgrown its skin and is trying to shed it. We’ve gotten too big and complicated and diverse to be labeled a Christian nation. Humanism fits the emerging need. Let’s make it happen.![]()

Carl Coon is the 2013 recipient of the American Humanist Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award.