Confessions of a Prayer-Struck Atheist

Is it ever intellectually honest for an atheist to pray? Indeed, can an atheist claim, without manifest absurdity, to have a relationship with God? Midway through my Iraq deployment as an Army journalist, these abstract questions seemed not only real but urgent.

My tour with the 207th Mobile Public Affairs Detachment lasted from August 2005 to July 2006. The base where I was stationed, Logistical Support Area Anaconda, had a reputation for its good amenities but also for its frequent mortar attacks. There, I worked as a writer and photographer for the base newspaper, Anaconda Times.

Late one evening I was alone in the living trailer I shared with one other soldier when I heard the alarm sound and felt the unmistakable vibrations of the mortar impacting the ground. I don’t want to exaggerate my danger, so I hasten to add that these attacks rarely harmed anyone. Soldiers who had spent several months on the base often talked about them the way old men converse about atmospheric disturbances. Maybe this was a façade, maybe not. As for myself, I never got used to them. I came to expect the mortars to come in pairs and I hated the sickening few seconds of suspense before the vibrations of the second mortar. It wasn’t like listening to thunder as a scared kid; you couldn’t count “one Mississippi, two Mississippi” to guess where the force from the sky was going to strike. No calculus existed for estimating the proximity of the next impact. All you could do was wait.

Late one evening I was alone in the living trailer I shared with one other soldier when I heard the alarm sound and felt the unmistakable vibrations of the mortar impacting the ground. I don’t want to exaggerate my danger, so I hasten to add that these attacks rarely harmed anyone. Soldiers who had spent several months on the base often talked about them the way old men converse about atmospheric disturbances. Maybe this was a façade, maybe not. As for myself, I never got used to them. I came to expect the mortars to come in pairs and I hated the sickening few seconds of suspense before the vibrations of the second mortar. It wasn’t like listening to thunder as a scared kid; you couldn’t count “one Mississippi, two Mississippi” to guess where the force from the sky was going to strike. No calculus existed for estimating the proximity of the next impact. All you could do was wait.

It was during one of these gaps that I fell to my knees and almost prayed. Then I stopped. I had, by this point in my life, rejected not only my parents’ Mormon faith but all religion and decided that I was a nonbeliever. I knew that prayer was irrational and, if I had to die, it might as well be rational to the last breath. The mortar attack passed and I obviously survived, but I never could forget the momentary lapse. Did this not show that, despite all my argumentation, I had failed to deracinate my childish impulses toward religion?

My next close encounter with spirituality happened on a small military installation in western Iraq. The environment surrounding Combat Outpost (COP) Rawah resembled the surface of an uninhabitable planet. Powdery “moon dust” caked the ground up to shin-height and forced troops to clean their weapons religiously. Mail and hygiene supplies had to be flown in. Summer temperatures routinely soared to 120 degrees Fahrenheit. It was the sort of place troops complain about while stationed there and brag about in equal part after leaving.

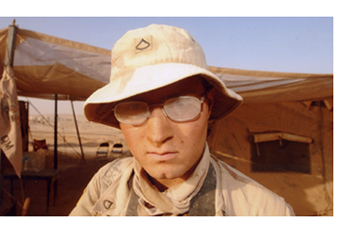

Within the first few months of my tour I made two trips to COP Rawah to cover the troops stationed there. The first trip, in which I came and went by convoy instead of air, was the more adventurous of the two. The day my staff sergeant and I had arrived to COP Rawah was also the day we got our first taste of “action” in theater when, on the convoy from Mosul, one of the five-ton vehicles hit a landmine that had probably been left over from one of Iraq’s previous conflicts. No one was seriously harmed to my knowledge, and the convoy arrived just in time for us to get the photos we needed before the light got too dim. Staff Sergeant Engles Tejeda snapped a photo of me after a low-flying helicopter plastered my face with moon dust. My ambivalent expression, filtered through dust-caked glasses, became iconic.

The transient housing was filled, so we slept on top of the same Humvee we rode in. This particular outpost had a policy of blackout during night, and the wind was low, so the view of the Milky Way was breathtaking. Staring up at the stars from my sleeping bag, I couldn’t help but note the contrast between the order and beauty of the cosmos and the human-made chaos of the country I was stationed in. It seemed comforting to think that whatever happened with humanity down here, there would always be something beautiful and orderly up there. So I silently said the last prayer of my life and it went something like this: Dear God, I have come to the conclusion you probably don’t exist, but I’ve also come to the conclusion that any one view I hold may turn out to be mistaken, however unlikely the odds seem. So if you are there, if I am wrong, you know where to find me.

In the summer of 2006 I returned from Iraq to my family in Pocatello, Idaho. I worked as a part-time writer for the local paper there and pursued a degree in philosophy at Idaho State University. Among the many deep and perplexing problems I mulled over was this: how am I to see these experiences in the light of my all-but-declared atheism?

The first case, I’ve decided, isn’t too hard to answer for. The old saying that there are no atheists in foxholes misses the point entirely, apart from its being untrue. A yearning to pray in moments of danger demonstrates no truth deeper than the fact that our hunger for self-preservation exceeds our rationality—already quite well established, I would think. The same impulse that made me want to pray might have inspired me to cross my fingers, wish upon a star, or rub a rabbit’s foot.

But a yearning to pray for the wonder at the stars is less easy to account for because it comes much closer to what most believers would consider a “genuine” religious experience. As I read more philosophy and literature, I came to realize that I wasn’t the only nonbeliever to have said goodbye to God. Nietzsche’s passage in The Gay Science, famously announcing the death of God, doesn’t speak of God’s demise with indifference; it is sad, terrifying, thrilling and, ultimately, triumphant. Anyone who’s ever suffered through a loss of faith can relate to the sense of disorientation described by Nietzsche’s madman:

“What have we done, we unchained the earth from its sun? Whither is it moving now? Away from all suns? Are we not plunging continually? Backward, sideward, forward, in all directions? Is there any up or down left?”

Thomas Hardy’s poem, “God’s Funeral,” also presents the recognition of God’s non-existence as an important event. In the poem, Hardy describes a funeral procession carrying “a strange and mystic shape.” He somehow recognizes the shape as God and joins the procession, bearing the grief of those who followed along with him. He sees people beside the funeral train praying, refusing to relinquish their faith, but knowing that he can never again be among them. In one of the most powerful stanzas, the speaker contemplates the void that God’s death has left behind:

And who or what shall fill his place?

Whither will wanderers turn distracted eyesFor some fixed star to stimulate their pace

Towards the goal of their enterprise?

For Nietzsche, the death of God is a great epochal event, for Hardy, it is an intimate loss. “And who or what shall fill his place?” is left an open question. I can’t say I have ever felt this kind of grieving for the loss of God because I never had what believers call a “testimony” of God’s existence. Still, I find myself sympathizing with Hardy, whose vision of God’s death demands more sacrifice of the nonbeliever. Nietzsche’s triumphant new age is certainly exciting, but I’m suspicious that one false promise is being used as a substitute for another.

I confess—with not a little embarrassment—that I have felt the pull of comfort offered by the theistic worldview and occasionally yielded to it. Yet through it all I have gained a deeper understanding of my own commitment to religious nonbelief and intellectual honesty. After reflecting on my experiences in the light of these passages and others in philosophy and literature, I have come to the conclusion that every serious nonbeliever must take a good hard look at what it is he or she is walking away from.