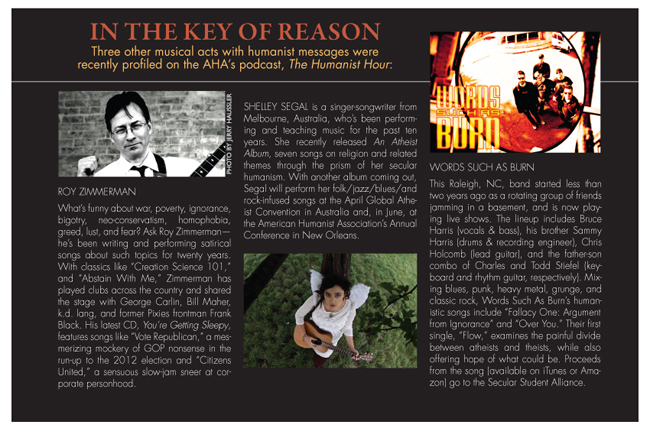

We Are All Where We Belong An Interview with Quiet Company’s Taylor Muse

Music with obvious humanistic themes is a rare find in today’s indie-rock scene. Of course, messages of reason and compassion appear in small doses across popular culture. But entire concept albums featuring great rock music intended to advance secular morality and appreciation of the material world have generally been only slightly more common than leprechauns and pink unicorns.

For the Austin, Texas-based indie quartet Quiet Company, however, the humanist worldview is an integral part of their musical vision. And their new record, We Are All Where We Belong, very clearly incorporates humanism into more traditional musical themes of love and introspection.

On We Are All Where We Belong, Quiet Company integrates a sound reminiscent of both Sufjan Stevens’ album Illinois and The National’s Boxer with the overarching narrative of lead vocalist Taylor Muse’s journey from a conservative Christian upbringing and belief system to a celebration of the power of human potential.

The opening track, “The Confessor,” begins with eerie organs and the lyric, “I don’t want to waste my life.” It quickly flows into what could be a bluesy gospel number, with an authentic Southern Baptist-style choir cooing while Muse sings of lost faith. “I don’t want to waste my life,” Muse repeats, and then triumphantly arrives at the chorus: “I don’t want to waste my life, thinking about the afterlife.”

Sometimes the lyrics are reactions to religion: “I once had the desire to believe that our lives had been planned out by an unseen deity.” At other times they’re more focused on understanding and expressing his inner life in a godless, existentialist world (“Don’t let me go, I’m not prepared. I’m so damned scared that I’m almost there”). But throughout the record, Muse shows an impressive musical, intellectual, and emotional range, hitting the high notes of arena rock while singing about healthy living post-Christianity just as skillfully as he manages quieter reflections on fears of mortality and his desire to be a good father for the sake of his daughter, not in order to please God.

In the final track “At Last! The Celestial Being Speaks,” Muse celebrates a humanism even some of his religious neighbors in Austin could appreciate, with a tongue-in-cheek invocation of God’s voice: “I don’t see why you should believe that you needed me, because you all belong to the earth I put you on. So lift up your heads, don’t worry about death, you’re all gonna be just fine.” With this statement, surrounded by a series of hallelujahs from the choir, the record comes to a close. As listeners, we’re left to reenter the world with a newfound appreciation for this life, the only one we know we’ll get.

Citing influences as varied as Kurt Vonnegut and religious scholar Bart Ehrman, Muse hopes Quiet Company’s new record can be a window into creating communities for nonbelievers that could fill the holes of fellowship left behind with religion. “Humanism ought to be doing more to create communities that are recognizable,” Muse notes. “Humanity has such potential for kindness and intelligence, but also evil—all of those things are our responsibility, up to us to achieve or to prevent.”

So might the humanist movement be able to build on Quiet Company’s achievement? Muse thinks humanism could one day inspire just as much art as has religion. Just as Pink Floyd’s The Wall re-imagined notions of tyranny and oppression, future musical projects could help create a new understanding of what it means to be a humanist. After all, it isn’t just great scientists and thinkers who drive this movement, but great artists as well.

We had the opportunity to speak to Muse by phone in November 2011 about his humanist philosophy, his upbringing, and his band’s latest album.

The Humanist: Could you tell us a bit about your story, and the experiences this record came from?

Taylor Muse: I was raised in the Bible Belt, where religion is really a part of every facet of our culture. Especially in East Texas where I’m from, if you don’t have a church to belong to, you just don’t have anything to do—it’s that engrained in the culture. My family is very religious—my brother is a minister, my grandfather was a church song leader—so it’s a big part of our family dynamic. I was a believer myself for a long time.

After I’d completed two years of college, and was living in Tyler, Texas, I decided to move up to Nashville, Tennessee. I saw living in a new city as an opportunity to reinvent myself. I started reading a lot more, all different kinds of things, and happened upon Kurt Vonnegut’s novels. That was when I first read Slaughterhouse Five, and something about the way Vonnegut wrote, and what he wrote about, and things that he clearly felt, really spoke to me on a level that nothing else had before. He would talk about humanism and socialism—and these were words that I knew very little about except from the church’s perspective, which was always very negative. The basic message was: humanism is the antithesis to religious thought.

The Humanist: And they used that word, “humanism”?

Muse: Actually atheism was the big word, and we were taught that atheists are bad people. Humanism was a word that I’d heard associated with atheism, but never really knew much about, other than the negative connotation. But when Vonnegut wrote and talked about it, it just made so much sense. It was beautiful to me the way he rationalized morality, much like Mark Twain, and I became obsessed with reading everything I could about and by Vonnegut. In turn this really got me thinking about morality, and why I believe what I believe. This was my first big step away from religious fundamentalism, and my first real foray into humanism.

The Humanist: What about this idea that we are all where we belong? That’s the title of the record, and similar lyrics pop up in several of the songs. You also spoke about the idea of everybody in Texas having a church to “belong” to.

The Humanist: What about this idea that we are all where we belong? That’s the title of the record, and similar lyrics pop up in several of the songs. You also spoke about the idea of everybody in Texas having a church to “belong” to.

Muse: Certainly in the church, and this is very much represented in Christian music as well, you hear a lot about how Earth is not our actual home, that Jesus will come down to bring us to our real home, where everything will be perfect. I’m sure I’m not alone in thinking this removes all incentive to make this world any better. That is, when you believe that all you’ve got to do is die and all of a sudden your problems will be solved, why bother?

I view this as a very harmful belief to hold, because it nullifies any inclination to work hard or to be better. So I really wanted to address that and say, no, you don’t belong anywhere else—here is where you belong. This home, this life, it’s all you can reasonably believe you’ll have, so it’s your responsibility to make it as pleasurable or as worthwhile as you can. One of the things I love so much about humanism is that it’s about taking responsibility for yourself and for your community. There’s just so much potential in humanity, and the more that I think about Christianity, I see it as a crippling belief that’s constantly championing weakness. This idea that “we can’t do anything and we’re not worth anything without our savior”—it’s so harmful.

There are a couple of lines on the record where we talk about belonging to the land and to the sea; I wanted to keep it very tied to the natural world.

The Humanist: We move away from religion and sometimes it’s a little bit isolating, but at the same time there are other ways to find community—you can find it through a music scene, or through your family or your friends. What do you think about the idea of finding belonging in a humanist community?

Muse: Community is one of my favorite things to talk about because we really strive to create one around our music. And it’s the most important thing in all of humanism, I think—this idea of creating and serving your community. I was recently on the Humanist website where Bart Ehrman had some really great things to say about humanism being out and open, and the need to create communities that are specifically humanistic for people to join. Ehrman believes we need to create some sort of recognizable community, in the way that churches are so easily spotted in any town. I think that’s really smart, and I’d like to see it happen.

The Humanist: Talk a bit about the subtitles of the songs on the record, such as: The Utterly Indifferent,” “This Is the Worst Crazy Sect I’ve Ever Been In,” and “The Harlot and the Beast are Dating!” You come up with some really interesting stuff here.

Muse: Some of them are kind of funny, some more serious; some allude to the context of the song, and some are entirely unrelated. A lot of them are references to [the animated Comedy Central series] Futurama (laughs). In an episode called “Godfellas,” the character Bender, a robot, gets shot out of a cannon and finds himself floating through space indefinitely and they can’t find him or rescue him. He ends up playing God to this group of tiny creatures that live on his chest, and eventually he kills them all. He then actually meets God and has a conversation with him—it’s just a very funny, clever episode, with so many quotable lines, and that’s where “This Is The Worst Crazy Sect I’ve Ever Been In” comes from, along with “You Were Doing Well Until Everyone Died.” So you see there’s nothing specifically deep about the subtitles.

Two of the first songs we wrote for the record were “Preaching the Choir Invisible” Parts I and II, and I knew from the start I wanted to have parenthetical subtitles with them. We used “What Do You Think Happens When We Die?” with one and then switched over to “What Do You Think Happens When We Live?” for the other. We really liked the idea and figured it would be an interesting thing to continue throughout the record.

The Humanist: One song we really like is “You, Me and the Boatman.” You use the image of the Boatman on the front of the record, and there are several allusions to rivers in the lyrics. Does the Boatman become a symbol for humanism? How did you come up with that?

Muse: He’s more a symbol of death, meant to suggest Charon from Greek mythology, who ferries people from one bank of the River Styx to the next. I mean, what is religion really if not an organized panic about death? We just wanted to harp on that a little bit. So much of the record is about dying and how religion has been a disappointing comfort for that. So the Boatman makes a few appearances, especially in that song.

Love is another thing we sing about a lot. We tend to be pretty romantic, and I write a lot of songs for my wife. But you know, I think the best love stories are often set against the specter of death. And again, it’s humanistic—the sense that this world is all we have, this time is all we have together, so let’s make the most of it. Let’s make our lives worth living as much as possible.

The Humanist: Certainly the lyric, “Live to love and love to live” (from “You, Me, and the Boatman”) goes a bit deeper than your typical love song. It’s also about how to approach life in general.

Muse: My wife and I both feel very strongly that we have to make the most of the time we have together—that’s part of the reason I have such a problem touring and going out on the road for long periods of time. Our lives really revolve around how much we love each other, just like hopefully most people’s will at some point in their lives. I guess the two messages are really intertwined.

The Humanist: It’s an interesting message—you’re saying, “I could try to be a big rock star if I wanted to be, but I actually love my life, I love my family.” It’s not something that would typically be thought of as a humanistic message, since people often think of humanism as not having much to say beyond “There is no God.” But your statement about love could potentially be a very humanistic message. Do you think of it that way?

Muse: I think of it as the most humanistic message. Humanism to me is so much more than doubting if there’s a God. It’s also an entire structure for how to appreciate your life—not inhibiting yourself in any way. Loving who you want to love. Doing what you want to do, if there’s not a compassionate reason not to. To me, humanism is the most liberating, love-encouraging type of mentality to have. So when I think of love, it’s definitely in very humanistic terms.

The Humanist: Before we let you go—you talked a little bit earlier about how humanistic artists should actually try to pull their humanism into their art. What do you think the future shape of that should be? Do you think we should have humanistic choirs, do you think we should somewhat model religious music?

Muse: It’s so vastly different from religion, it’s not dogmatic at all—so I don’t see any reason why we should have to conform to that model. Humanism allows such an opportunity to be creative, and to push ourselves to artistic heights and reach our potential as creative humans. We should think about other ways we can express ourselves—obviously, music is always a viable option, and we can sing about how we don’t believe, but how long can we sustain that? One place I think faith gets so romanticized is in film, and I’d really like to see more filmmakers explore [the humanist] realm.

I don’t know that we need choirs or churches, but I think there are a million ways, if we apply ourselves, to create more opportunities for community.