The Humanist Dilemma: What to Do When People Continue to Actively Grieve Years after a Death

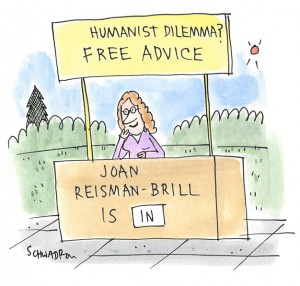

Experiencing an ethical dilemma? Need advice from a humanist perspective?

Send your questions to The Humanist Dilemma at dilemma@thehumanist.com (subject line: Humanist Dilemma).

All inquiries are kept confidential.

Perpetual Mourners: I have a friend I can barely bear to remain friends with. She lost her husband a decade after I lost mine. When I lost mine, she was not by my side comforting me, which I didn’t particularly notice or resent at the time because I had plenty of other friends and family to support me. But since her husband died, she calls me all the time, crying over her loss, talking about how terrible her lot in life is, demanding to stay at my vacation home when it’s really inconvenient for me (she doesn’t take no for an answer), commanding me to drive her places (I’m considerably older and less fit than she is), and making a total pain of herself (she is not a pleasant house guest—picky, demanding and a slob, and all she talks about is herself). And once she makes plans with me, if something better comes up for her, she just drops me without notice or apology.

It’s been three years since her husband died, she has children and grandchildren, and she’s extremely well off financially, but this behavior isn’t dying down. I’m so tempted to ignore her calls. She just doesn’t pay any attention to anything I say.

—Sorry for Your Loss—Now Get Lost

Dear Lost,

I hear from a widow who is friends with many other widows, and there’s one among them they all refer to as “the Bereaved“ because for years she has been brandishing her widowhood as her ticket to attention and privilege, even though the rest of them are just as deserving, just not as needy or demanding. Why they put up with her, I don’t fully understand—except to ridicule her when she’s not around. I also know a family who lost their husband/father decades ago, but they carry on as though it was yesterday, bursting into dramatic sobs ten years later about his passing at my own father’s funeral.

I also encounter people who’ve lost a mate, sibling, or child and carry on almost as though nothing had happened, returning to their usual activities, paying attention to other people’s needs, and doing their best to own their current life despite the terrible loss they feel every minute of every day. They don’t deny or ignore their grief, they just absorb it in their forward progression, gracefully incorporating loss as an inescapable part of life.

Everyone experiences loss differently. Some bounce back quickly, others carry pain longer and more acutely and are more debilitated. There’s no right or wrong duration or degree of grieving, nor is it better to be stoic vs. dramatic, closed or open. But there are appropriate vs. inappropriate expectations and demands. Although the Bereaveds of the world may believe their tragedies are greater and more painful than those of their friends, or that they themselves are less equipped to deal with grief—and I suppose, based on their behavior, that might be true—it’s not your duty to fill the void. Urge your friend to seek counseling through a support group, therapist, even a spiritual leader if your friend is religious, but tell her she can’t continue to place demands on you. Then be firm about not being available to chauffeur or host her, which are really separate issues about her habits and taking your friendship for granted. In that regard ask for favors when you could use them, and berate her when she stands you up (if you give her any more opportunities to do so). Maybe if you mimic her, she’ll recognize how she feels to you. Or she may just start avoiding you, which works too.