Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Black Panther: Promising Sign for Future of Comics Series

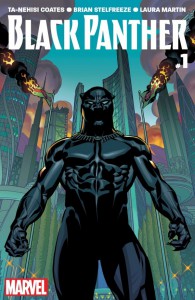

Last Wednesday was an exciting day in the world of mainstream comics as it marked the much-anticipated return of the Black Panther superhero series, this one by acclaimed author and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates, veteran artist Brian Stelfreeze, and colorist Laura Martin.

The eleven-issue series features T’Challa, who is the king of Wakanda and a superhero known as the Black Panther (no relation to the Black Panther Party). Launched in advance of the Marvel Studios eponymous film set for release in 2018, Black Panther has certainly attracted attention from comic book fans and Coates’s audience, with preorders for this first issue reaching over 300,000. As both a burgeoning comic book enthusiast and fan of Coates’s writing, Black Panther #1 did not disappoint me. In fact, compared to the racially tone-deaf and unenlightened Daredevil that I reviewed two weeks ago, it’s the refreshing opposite. The writing is deliberate—concise and exquisitely intertwined with the art in moving the story forward, while carefully encompassing the frustration and rage of a society in transition, successfully embodying the question Coates wishes for us to grapple with: “Can a good man be a king, and would an advanced society tolerate a monarch?”

For those who laud this reboot because T’Challa is black (Black Panther was the first mainstream black superhero—created in 1966 by white males Stan Lee and Jack Kirby), it’s only the surface that’s being celebrated. While it’s no doubt a victory to have more people of color in lead roles (actually, the entire country of Wakanda is black), Coates doesn’t stop there.

@tanehisicoates Will you be incorporating real social & political issues of today into the Black Panther series?

— J. Matt (@JohnnyMPozzi) March 14, 2016

Yes. Arc is a post-colonial, post-modern, deconstructionist look at militarism, imperialism and heteronormativity. https://t.co/LHemNDt6AU

— Ta-Nehisi Coates (@tanehisicoates) March 14, 2016

Wakanda is not only an African setting (the majority of superheroes seem to gather in New York, or at least in the United States unless they are “exotic”), it draws from African cultures and civilizations. In describing his conceptualization of what Wakanda looks like, Brian Stelfreeze told Marvel:

Wakanda is one of the biggest characters in this new series so we’ve given that quite a bit of thought. I want the country to have a duality of old world and city of the future….Ta-Nehisi’s script feels very African, so I wanted the art to reflect this. I’m pulling from cultures all over the continent to establish the look: Masi tribesmen, Ancient Zulu warriors, and even modern Kalashnikov-wielding rebels will all influence the look of Wakanda.

As Coates told Vulture, the Wakandan language is also based on several real languages, since there is no “official version” in the canon: “I could have created a Wakandan language from scratch, but the idea is that Wakandan, as represented to the reader, pulls from a variety of African languages. [The language is] imagined as an amalgam. I think there’s a little bit of Hausa in there. There might be some Swahili in there. There might be a little bit of Shona in there.”

And although the woman who is stirring up unrest in Wakanda to T’Challa’s woe is unnamed in the issue so far, readers have been told her name is Zenzi, which, according to In These Times, alludes to the famous South African freedom fighter and singer Zenzile Miriam Makeba, aka Mama Africa.

Wakanda is also uniquely Afrofuturistic, subverting the mainstream equivalency of Blackness or African-ness as criminal, primitive, or urban. Here is a civilization that has never been colonized, that is not only self-sufficient but affluent and technologically advanced—in fact, it benefits from a supply of vibranium (the material that composes Captain America’s shield). T’Chaka, former king of Wakanda and T’Challa’s father, “refused to grant first-world economies access to Wakanda’s vibranium, and a cabal of powerful operatives had him assassinated.” It’s a setting examined all its own, a fictionalized setting replete with allusions to real underrepresented histories in mainstream America, untouched by imperialism or subservience to any European or North American nation, and operates with scientifically advanced technologies (that look like traditional African objects) that compete or supersede that of first-world nations.

In addition to the dynamic characterization of Wakanda, Coates offers a strongly feminist depiction of the Dora Milajae, the royal guard composed of women:

I’ve always seen the Dora Milaje as a bit problematic, and that’s going to divide me from most fans of the Black Panther. One of them is taken from every tribe in Wakanda and brought in, and T’Challa has the option of taking one of them as a wife. [I don’t like] the idea of these scantily clad bodyguards for this dude who’s the king and the notion that he doesn’t abuse that or that this is okay. I wanted to do something different. I try to see them as independent people and not people who we see strictly through the gaze of the male comic-book fans.

In this first issue, both Ayo and Aneka of the Dora Milajae are not only major players with major page real-estate, but a black lesbian couple. The elation caused by this fact is best expressed by L.E.H. Light on Black Nerd Problems:

Did Coates just take over the reins of one of the seminal Black comic book characters—a character who sold the 300,000 copies before it ever hit the stands—and center in the plot, in the first issue, a Black lesbian couple? Yes, he did. Did he then have those two women discuss the nature of love AND the nature of democracy in 4 panels? Yes. He. Did. Did he then have them put on some amazingly cool armor and threaten to burn the mf’er down? Oh yeah, he most certainly did.

And we know Coates was very intentional in his choice of character visibility. In The Atlantic in a note on the “Feminists of Wakanda,” he writes:

Through much of my time collecting comic books I never took much issue with how women were drawn. I had a vague sense that there was something about, say, the reworking of Psylocke that bugged me. But I simply didn’t give it much thought. It never occurred to me, for instance, to ask whether a superhero’s pose was anatomically possible. It never occurred to me to ask why a superhero would have a DD cup-size. Was that for her benefit or for mine? I never asked.

The feminist critique of comics has made “not asking” a lot harder. That, in itself, is a victory. The point is not to change the thinking of the active sexist. (Highly unlikely.) The point is to force the passive sexist to take responsibility for his own thoughts.

This is not the first revitalization of the comic book industry to include more dynamic portrayals of women, LGBTQ individuals, and people of color—in fact there are many of note including Silk (Asian-American Spiderwoman), Bitch Planet, Monstress, and the South African superhero Kwezi. But it’s a hopeful one backed by Marvel, Coates’s reputation outside of mainstream comics, and Coates’s eagerness to create a series that wields the virtues of the comic book world (while wiping away its faults) to inspire a better reality. In short, Black Panther is worth the read.

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that the creators of Black Panther were Stan Lee and Gene Colan. In fact, the creators were Stan Lee and Jack Kirby.