I Loved Lucy (Spoiler Alert: This sci‒fi film contains both science and fiction!)

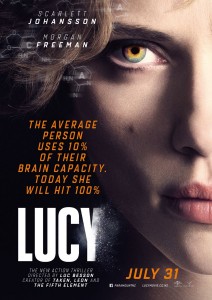

Despite impressive box office numbers, mixed reviews suggest not everyone’s crazy about Luc Besson’s new film Lucy. A Rotten Tomatoes audience score of 48 percent isn’t what you’d expect from a sci-fi movie about brain capacity starring Scarlett Johansson and Morgan Freeman, but that’s exactly what it received, along with a fair amount of criticism. Even so, Lucy had my synapses firing!

The movie begins in Taipei, Taiwan, where twenty-five-year-old American college student Lucy (played by Scarlett Johansson) is studying. After a squabble with her new boyfriend, Lucy finds herself handcuffed to a briefcase with something mysterious inside. Shortly after, she’s knocked out and awakens to find she’s a drug mule for the owners of the mysterious contents of the briefcase—a blue crystalline synthetic drug called CPH4.

With the drugs surgically stashed in her lower intestines, Lucy is kicked in the stomach by a captor, exploding the bag and releasing a massive amount of the synthetic drug into her system. We witness Lucy’s physical and mental transformation and are reminded of how much more of her brain is being used when ever-increasing percentages pop up on screen—20%; 30%; 40%. These higher percentages correlate with her brain capacity usage, but also her mastery of what writer/director Besson dubs the “steps of control”: 1) control of the cell; 2) control of others; 3) control of matter; and 4) control of time.

Throughout Lucy’s transition, she gets advice from Professor Norman (Morgan Freeman), a doctor and scientist who has contributed to the “steps of control” theory. Lucy is noticeably different and is utilizing the drug’s enhancement, but realizes that she is accelerating too quickly for her human body. Will Lucy will reach 100 percent brain capacity and be able to travel through time and space, or will she destroy herself trying?

In addition to the tension created by the ramping up of Lucy’s brain power, the actual science Besson integrates into the film is really interesting. Many critics were all over Besson for using the debunked “we only use 10 percent of our brains” myth. But Besson knows this! In a recent interview on Vulture he said, “It’s totally not true. Do they think I don’t know this?” Apparently, Besson researched the concept for nine years and although the 10-percent myth isn’t real, there are some aspects of the film scientists have “logically” agreed upon.

Herein lies the beauty of Lucy, offering a healthy dose of both fiction and scientific truth. Google “science fiction” and you’ll find this fluid definition: “fiction based on imagined future scientific or technological advances and major social or environmental changes, frequently portraying space or time travel and life on other planets.” I think Besson does a fantastic job working within this definition, but also stretching it to make us question just how “fictional” the story is. The French filmmaker has said that this is the “magic of the film”—that you can mix things up a bit, things that are “true” and “false,” and by the end of a film people are questioning reality, which is the fun of it.

Interestingly enough, Besson says CPH4 does exist—it’s just not called CPH4. Speaking to CraveOnline he explains, “It’s a molecule that the pregnant woman is making after six weeks of pregnancy in very, very tiny quantities. But it’s totally real, and it’s true that the power of this product for a baby is the power of an atomic bomb. It’s real. It’s totally real. So it’s not a drug in fact, it’s a natural molecule.” Besson also claims to have spoken to “a lot of scientists” who believe that the “steps of control” theory is at least logical.

So, I can’t quite answer the meaning of life after seeing Lucy, but I can give you a suggestion if you decide to go see it: go into it with an open mind. Know that you’re not going to see a 100 percent scientifically accurate film, but expect entertainment with some sprinkles of scientific truth. Johansson is fantastic in the title role, as is Freeman as the science professor. And don’t forget to catch the subtle religious critiques strewn throughout. Besson may not realize this, but the message underlying Lucy is simple—we could be gods.