Oh Noah, It’s Unbiblical!

There are those who love all mythology equally: Greek, Norse, Celtic, Chinese, Indian, African, New World, Middle Eastern, and so on. For these folks, biblical mythology is unexceptional: it’s just as unbelievable and just as much fun as all the others.

Admittedly, I don’t know many people like that. When it comes to the Bible, most seem to revere it, hate it, or find it boring. Naturally, folks in the latter two groups aren’t likely to watch a movie depicting a Bible tale. And those in the former will do so only if it’s devotional. Given this demographic reality, how did anyone convince serious investors to finance a $125 million theatrical epic that would retell a tired old religious story in a manner geared to fantasy film lovers?

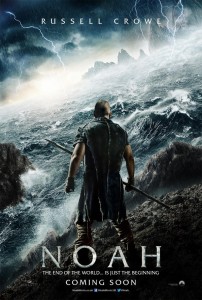

Yet here we are, less than a week away from the U.S. release of Noah, starring Russell Crowe, Jennifer Connelly, and Anthony Hopkins. At the helm is celebrated director Darren Aronofsky (Pi, Requiem for a Dream), who says he’s been fascinated since age thirteen by the Noah character. When his seventh-grade teacher told his class to write on peace, Aronofsky penned a poem called “The Dove” about the bird that returned to Noah with an olive branch. The work went on to win a United Nations contest, giving Aronofsky the confidence to become a writer.

So, years later, when working with producer Ari Handel on the film projects The Fountain, The Wrestler, and Black Swan, Aronofsky collaborated with him over the better part of a decade to develop a screenplay for Noah. The two then turned to Canadian artist Niko Henrichon, who adapted the screenplay into a graphic novel, first published in Belgium in 2011. Not surprisingly, the novel includes giant six-armed angels and fantastical animals which, critics say, appear in the film as well.

The motion picture premiered March 11 in Mexico City, where Aronofsky told the crowd, “It’s a very, very different movie. Anything you’re expecting, you’re fucking wrong.” That same day, in an interview published in the British publication, Christian Today, he said:

In the same way that Middle Earth was created, we decided to create a world out of the clues from the Bible. We were able to build something that’s fantastical, but very truthful to the story. I really think this is the perfect film to bring believers and non-believers together, to develop a conversation between both sides.

Not surprisingly, the Internet Movie Database originally categorized the 2-hour and 18-minute epic as “Adventure/Drama/Fantasy.” But now the “Fantasy” has been dropped.

As for Noah the man, Aronofsky has described him in interviews as “a dark, complicated character” who, in the aftermath of the flood, experiences “real survivor’s guilt.” He also sees Noah as “the first environmentalist.” In this regard, Christian screenwriter Brian Godawa, after reading an early version of the screenplay in 2012, describes the Noah depicted there as “a kind of rural shaman, and vegan hippy-like gatherer of herbs.”

Noah explains that his family “studies the world,” “healing it as best we can,” like a kind of environmentalist scientist. But he also mysteriously has the fighting skills of an ancient Near Eastern Ninja.

Given this effort to modernize and render hip what has been a Bronze Age flood myth transformed into a Christian salvation parable, evangelical pundits have declared Noah to be unbiblical and therefore unsuitable for Christian audiences. Or, as Bill Maher characterized it on HBO’s Real Time with Bill Maher, “They’re mad because this made up story doesn’t stay true to their made up story.”

Focus groups haven’t exactly been kind either. This past fall the studio held test screenings for Jews in New York, Protestants in Arizona, and the general public in Southern California. All had problems with the film. This created conflicts between the director and the studio heads, with the studio creating various re-edits in a rush effort to render the work more biblical. But none of the experimental cuts did well either. And now Aronofsky has implied that the studio has gone back to his original.

Meanwhile, National Religious Broadcasters has successfully led a campaign by a number of evangelical groups to pressure the studio into placing the following disclaimer on trailers and marketing materials.

The film is inspired by the story of Noah. While artistic license has been taken, we believe that this film is true to the essence, values, and integrity of a story that is a cornerstone of faith for millions of people worldwide. The biblical story of Noah can be found in the book of Genesis.

This is Paramount Pictures warning a portion of its target audience to think twice before buying a ticket! Did these evangelical groups threaten to organize a boycott if Paramount didn’t capitulate? If so, how come this never happened to earlier treatments? There is simply no Hollywood depiction of this particular Bible tale that has ever been faithful to the text: not the early talkie of 1928, Walt Disney’s “Silly Symphony” cartoon of 1933, the three-hour television miniseries of 1999, or the comedy Evan Almighty of 2007. So why such fretting now?

And if that weren’t enough, Muslims have jumped into the act. Noah has already been banned in Bahrain, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates and become the subject of a fatwa by Al-Azhar, the top Sunni Islamic institute in Egypt. The countries of Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and Tunisia are expected to ban the film next.

Bill Maher sees a silver lining here. With both Christians and Muslims now condemning the movie, “it must be doing something right.”

Even the nature of the critiques suggests the same thing. For example, many in the evangelical community fear the film advances a liberal, political message—not liking it when Aronofsky said, “It’s about environmental apocalypse which is the biggest theme, for me, right now for what’s going on on this planet.”

There’s more. An unnamed commentator for the evangelical Beginning and End blog writes, “Humans have compassion, while God in the film only has irrational wrath… This film reflects a lack of faith and promotes the idea of doubting God, rather than believing.”

At the 2011 Provincetown International Film Festival, where he’d received a career-spanning award, Aronofsky spoke of the Noah’s ark story as “a great fable that’s part of so many different religions and spiritual practices.”

So this gives humanists some ground for optimism that maybe those seeing the film will absorb a few ideas more to their liking. But it’s going to take a lot more promise than this to get the godless demographic to shell out what it’s going to cost to see this thing, especially the version in 3-D IMAX. And that promise doesn’t seem to be materializing. Noah opened to mixed reviews and muted audience response in Mexico City, which suggests that Aronofsky’s boat isn’t seaworthy enough to handle the long voyage necessary to keep Paramount from taking a bath.