A Humanist Visits the 9/11 Memorial Museum

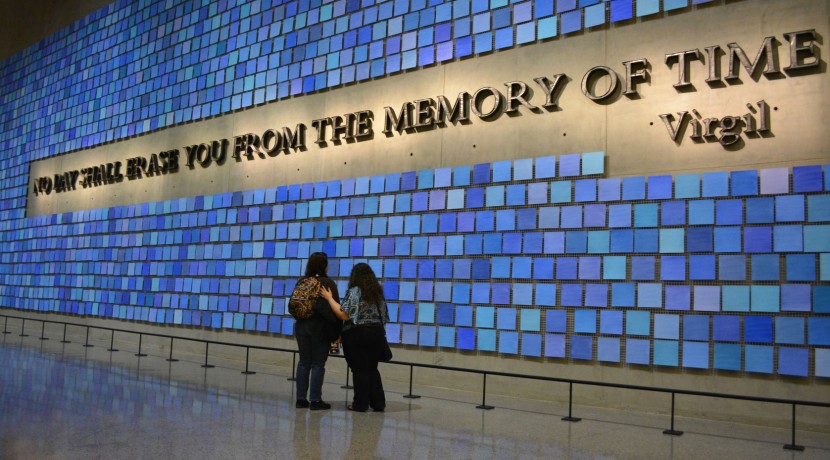

A Virgil quote in the 9/11 Memorial Museum. Photo by Christopher Penler/123RF.

Let’s start with a conclusion: the 9/11 Memorial Museum, the displays and artifacts it houses, and the memorial park in which it is all situated, are a spectacular success.

Like many New Yorkers of my humanist-liberal stripe, I had no intention of ever visiting the park, let alone paying admission to the museum. After more than twelve years of 9/11-related pompous piety and political posturing, proposed designs both grandiose and unworkable, petty bureaucratic turf wars, and the endless tooth-and-nail squabbling by dozens of interest groups with both real and imagined claims on our collective memory of what we all now all simply call “9/11”—which conservative columnist Peggy Noonan called “the narcissism of small differences”—I had no interest in visiting what I thought would be a shrine to more of the same.

Wrong. It’s a beaut. It works. And I’m glad TheHumanist.com asked me to take a humanist look.

It’s 8:45 on a Saturday morning, and after staring into the park’s beautiful sunken fountains for a few minutes, I turn the corner around the blank steel outer walls of the museum and see somewhere between 200 and 300 people in line at the entrance, all clutching the same e-ticket I have for the 9:00am opening. But the line moves swiftly even as it grows longer behind me, and in a few minutes I step from bright spring sunshine into a gray cavern.

If “cavern” suggests vast space to you, then I have chosen the right word. The outside dimensions of the museum belie the enormous volume of its interior. This is an underground museum – seven stories down to the very foundations of the original twin towers. And in spite of literally thousands of displays and artifacts within it, a visitor feels a deep-in-the-earth emptiness, emphasized by subdued lighting and a gathering grayness as we descend.

The first display in which humanists may be interested is the Virgil quote: No day shall erase you from the memory of time, pronounced on a middle level in a 60-foot long inscription of 15-inch letters cut from steel of the towers. Someone must have thought it was a classy quote with which to memorialize the 9/11 victims, but the “you” Virgil was writing about in the Aeneid was a pair of murderous Trojan warriors (gay lovers, by the way) who had just hacked to death sleeping Rutulian soldiers, and then been killed themselves. The incongruity has been pointed out many times, but the inscription stands.

“SEPTEMBER 11, 2001” is the simple title of the main exhibition that threads through the lowest, foundational level of what New York Times art critic Edward Rothstein called “a museum of experience.” And it is an experience like no other I have had. Divided into Before, During and After sections, and starting with the “We have a report …” interruption of NBC’s Today show, it presents the events of that awful day and its aftermath in TV clips, photos, short looped videos, and seemingly countless artifacts. (If you walk more hurriedly than I did, you’d miss the footage, behind a blank wall, of people jumping from the towers.) But most moving of all are recordings made by survivors—and poignant phone calls from the soon-to-be-dead—that are matched to minute-by-minute explanatory schematics of the towers, of the Pentagon, and of Flight 93 that crashed in Pennsylvania. There is a reason there are tissue dispensers wherever one of the dozen or more different two- to eight-minute “shows” are projected.

“Islamist extremist group.” “Islamist terrorists.” The Museum does not pull punches in describing exactly who committed the atrocities, and why, in either its literature or in “The Rise of Al-Qaeda,” an eight-minute film narrated by Brian Williams on the Afghanistan/Osama bin Laden/”Islamist extremist” lead-up to 9/11. There have been many Islamophobia complaints about that, but not from this observer.

The infamous “Miracle Cross” is in the After section and, in spite of my worst anti-theist, humanist imaginings, I’m okay with what the museum has done. It’s not treated as a “miracle” nor given any special place or attention. It stands in a small grouping of artifacts that the exhibit card said gave some workers “spiritual solace.” Let’s face it: the damned thing is part of the 9/11 story. It was dragged out of the wreckage by construction workers, who did make a big deal of it (as did professional theists with agendas) and it was part of the media circus for a long while. But the museum treats it as just one more artifact among many. You really could walk by it without noticing it, and while I stood there at least 10 minutes taking notes, I did not see any special attention being paid to it.

Now on to the museum store. Much has been made by the easily offended about the appropriateness of selling knick-knacks on “hallowed ground.” Hello? This is America—we sell stuff. So yes, $20 plush dogs and teddy bears; $13 book marks; NYPD and Fire Department t-shirts, sweatshirts, hoodies and badges; jewelry, charms and chachkas from $3 to $65; $20 commemorative mugs (as Sarah Silverman said on Real Time with Bill Maher, “How could you remember 9/11 without a mug?”) and loads of “I Love NY More Than Ever” crap for tourists who wouldn’t live here on a bet. This is all on top of a $24 admission price ($18 for seniors like me, and Tuesday evenings are free). Why? Because Congress, New York State and New York City, in their collective wisdom, appropriated zero dollars to cover any of the museum’s $63 million annual operating budget. And I saw no religious references in or on any of the materials. Let’s just get over it.

None of the gift shop offerings tempted me, so I headed for the escalator to leave and mused again on the silence after the subdued conversations in the store. Wait, not quite silent … what’s that canned music? Of course: “Amazing Grace.” Ah, what the hell—one more small offense to humanist sensibility, and I guess it could have been worse (Barbra Streisand’s “You’ll Never Walk Alone”? Tom Jones’ “I Believe”?).

Sunshine, finally, was never more welcome. The 9/11 Memorial Museum is exceptional and successful—not one to like, but one to respect. Visit once—but only once.Tags: 9/11