Why I’m a Black Man Against Black History Month

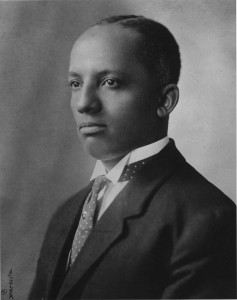

Carter G. Woodson, often cited as the "father of black history."

Carter G. Woodson, often cited as the "father of black history." This piece is partially inspired by A Black History Month Challenge, something I hope everyone reading this will participate in. The Black community isn’t a monolith, but we generally appreciate the purpose of Black History Month. But I also think it’s healthy to question things you have long taken for granted.

It isn’t so much that I’m against the institution of Black History Month but that I desire far more when it comes to integrating “our story” into the collective conscious of our society. The origins of Black History Month come from Negro History Week, a ninety-year-old bandage solution that doesn’t effectively address chronic distortions about Black America found in history books, public school programs, and culturally transmitted general knowledge of US history.

The tradition that evolved into Black History Month was never about needing an event to “commemorate how special we are.” Rather, a primary purpose of this annual observance was meant to combat the marginalization and erasure of our people’s influence in and contributions to US history that aren’t being taught in school.

Because historian Carter G. Woodson was well-versed in the dynamics of power, privilege, and oppression, he was outspoken against white supremacist history books as well as critical of the way schools indoctrinate students with white-oriented, anti-black education. This frustration inspired him to author his definitive and constructive critique of the educational system, The Mis-Education of the Negro.

Led by Woodson, the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) sought to do something about the way society devalued Black history and in 1926, proclaimed the second week of February “Negro History Week” to coincide with the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. Woodson wanted to capitalize off the tradition of celebrating this particular time to increase the likelihood of success. (So no, Black History Month isn’t observed in the shortest month of the year as a malevolent conspiracy.)

Over time, Negro History Week was adopted by education departments nationwide and, for that week, used literature and themes provided by the ASALH to incorporate instruction on the African diaspora. In the following decades, the ASALH pushed for integrating history curriculum in public schools to no avail. By the late 1960s, Black youth began pushing for month-long celebrations that ultimately led to the ASALH also promoting the change. In 1976, fifty years after the first Negro History Week, the US government officially recognized “Black History Month.”

It’s now 2016, forty years removed from the first official Black History Month. Sadly, many are resting on their laurels as if there’s no more work to be done. The goal of Woodson’s vision was to incorporate Black history into history classes that today still fail to teach a more evenhanded account of the past. The official statement from ASALH regarding the origins of Black History Month even states:

Woodson believed that the weekly celebrations—not the study or celebration of black history—would eventually come to an end. In fact, Woodson never viewed black history as a one-week affair. He pressed for schools to use Negro History Week to demonstrate what students learned all year. In the same vein, he established a black studies extension program to reach adults throughout the year.

It was in this sense that blacks would learn of their past on a daily basis that he looked forward to the time when an annual celebration would no longer be necessary. Generations before Morgan Freeman and other advocates of all-year commemorations, Woodson believed that black history was too important to America and the world to be crammed into a limited timeframe.

There’s adverse effects to these limitations. One notable consequence is the hero worship of a handful of prominent figures. What’s more, these particular stories tend to be sanitized and this selective representation is often at the expense of erasing a rich legacy of individuals, groups, and movements just as important.

An illustration of hero worship is found in the warped remembrance of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. that still plagues our cultural imagination. This distortion was confronted in Twitter’s #ReclaimMLK tag during Dr. King’s holiday weekend. Contrary to popular belief, Dr. King’s cause was as reviled then as the Black Lives Matter movement is in present times.

Often missing from the mythic narrative surrounding Dr. King’s memory are his references to the “bad check” the US has written Black America, how he owned an arsenal of guns and approved of armed self-defense against white terrorism, his criticisms of white supremacy and white privilege, an initiative to aid economic justice for the poor, and his very pro-social justice views.

And that’s just one man. Consider all the other tainted, lesser known, or unknown stories.

This is why professor and former civil rights era activist Charles E. Cobb Jr. once said, “The way the public understands the civil rights movement can be boiled down to one sentence: Rosa sat down, Martin stood up, then the white folks saw the light and saved the day.”

Does this mean we do away with Black History Month right now and never look back? No, not really.

While Black history is part and parcel to US history and ought to be taught as such, we haven’t yet reached the point where this nation’s history is recognized in a more authentic and integrated way. It’s difficult to achieve the goal of integration when everyday racism and anti-blackness propaganda leads to white-centered accounts of past events. I get why it’s become vogue in recent years but “post-racial America” is a fantasy we haven’t yet attained.

If we’re to one day do away with Black History Month—and I hope that day comes sooner rather than later—then understanding why the initiative got started helps. Next, we all must do our part to counteract the social disease of miseducation that greatly limits positive portrayals of blackness as well as the numerous times Blacks have impacted American culture and politics. Our influence on the direction and ethos of this nation includes our struggle against systemic degradation as well as the work of Black reformers, intellectuals, and educators.

The spirit of Black History Month should exist within school history curriculums to groom younger generations to be more socially aware. We need to promote critical examinations of a more unadulterated history. When educators, publishers, policy makers, and the media cease trying to deemphasize the role of slavery in the Civil War, reimagine slavery in more palatable ways, mischaracterize slaves’ complicity in their oppression, downplay the persistence of racism, require a “positive spin” on history, and dissolve anti-black media bias, then we can begin real talks of ending Black History Month.

This country must face its legacy of anti-black racism before systems that maintain anti-black racism can be demolished. Until then, the objective of Black History Month will remain confined to a twenty-eight day observation rather than function on a more extensive level permeating history classes, media depictions, and this country’s collective conscious.