Latino Humanists, Now and Then

Surely most Americans by now know who Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and Christopher Hitchens are, the standard-bearers of atheism. But what about humanists and atheists from non-English speaking countries?

We stand to enrich ourselves and our minds when we get to know the thinking of humanists from countries other than the United Kingdom and the United States. Take Umberto Eco, the renowned Italian semiotics professor and notable author of the medieval mystery novel The Name of the Rose. Did you know that he and Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini authored a book titled Belief or Nonbelief in 1999? Even though it was marketed as a confrontation, it is in fact a conversation between a nonbeliever and a believer in a surprisingly insightful and open tone.

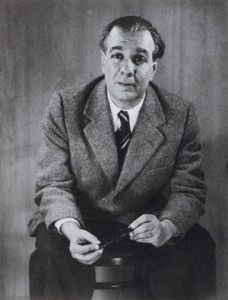

Hector Abad. Photo by Daniela Abad via Wikimedia Commons

As a Latino humanist, I sought to discover well-known humanists from Latin American countries; it also happens to be Hispanic Heritage Month. These humanists often fly below the radar because they haven’t published or written anything in English. Take the Colombian author and journalist Héctor Abad Faciolince, whose Angosta was a best-selling novel. Faciolince had this to say about the belief in the divine (translated from Spanish):

“I don’t need a god to explain to me why there’s human, animal or vegetable life. To credit a supreme being with the creation of Earth, the solar system or the universe seems to me a very odd invention. I think it’s an unnecessary hypothesis. I believe science, rather than theology, has better answers to questions about life, the existence of things or of the universe. Scientific theories appear much more robust to me, rather than appealing to a being we cannot see, hear and who does not manifest itself in any clear way. Let’s assume that there’s no God, would that change anything? I used to believe in god until my teen years because that’s what I was taught at home (my mother, sisters, grandparents), in the social environment I was reared and in school. However, my father had planted in me the seed of doubt in my tender childhood years, a seed that was later aided by other readings I made in my teens. I think that the belief or unbelief is imprinted very soon in the brain and it is very difficult to modify.”

Jorge Luis Borges

Another Latin American individual well known for his literary body of work, but not widely known for his humanism, comes from the country I was raised in, Argentina Noted writer Jorge Luis Borges had a very frank approach to atheism and his sharp analysis of religion has a hint of humor (translated from Spanish):

“I couldn’t define myself as atheist because to state that I’m an atheist would involve a certainty I do not possess. At the end of the day, the universe is so strange that anything is possible, even a God that is one and also three. To deny the existence of an all-powerful God, a good toothache suffices. God is so generous toward man that He gives him everything, even the possibility of Hell. However, who knows if those gifts are convenient, right? Buddhism is slightly less impossible to me than Christianity. Well, maybe I believe in karma. Now, as to whether there’s heaven or hell, I don’t. God… is the best creation coming from fantastic literature! Whatever Wells, Kafka or Poe imagined does not even come close to what theology imagined. The idea of being perfect, omnipotent and all-powerful is really wild.”

Speaking of Argentina, with a largely educated population and a state religion (Catholicism), many of the Catholics I’ve met in my life define themselves as non-practicing, espousing what we would call humanist values: fighting against discrimination in all forms, having a deep interest in local and global social issues such as poverty, women’s rights and political corruption, and honing a sense of social tolerance and hospitable nature to all.

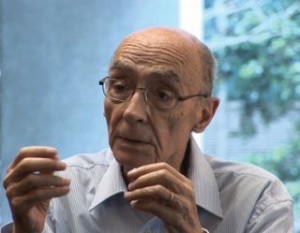

Jose Saramago. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Today we see a more pronounced polarization of positions, us versus them, which I consider to be less useful in discussing common threads of thought with believers and would-be humanists in our societies. Paraphrasing Richard Dawkins’ recent comments Twitter, we’re seeing a number of online media outlets that publish or attract comments from so-called offended parties just to grab clicks-per-page. I don’t believe in fanning the flames. That’s why I found José Saramago’s brief and reasonable statement all the more compelling and nonthreatening to believers:

“God and the devil are neither in heaven or hell; they’re inside our head. First we created God, then we became slaves to him.”

Saramago, a notable Portuguese writer (1922-2010), was the recipient of the 1998 Nobel Prize of Literature. Maybe Saramago sounds familiar to our readers because of his 1992 statements about the suffering of Palestinians. However, he was a very active atheist who bloomed later in life as a successful novelist.

To enrich our collective humanistic history, we need all the voices we can find and hear, in whatever language they speak and write. Let’s take time to listen to them and recognize their humanist beliefs.