Standing with Standing Rock: My Humanism Won’t Let Me Stay Silent

during the last week of October, I made a twenty-four-hour drive to join in the resistance efforts at the Standing Rock encampments near Cannon Ball, North Dakota. Hundreds of indigenous nations and non-Native accomplices had been gathering in solidarity with the Standing Rock Sioux tribe. I and other non-Native outsiders were shown love and referred to as “relatives.”

Before I begin to share my explicitly outsider view on a matter that doesn’t directly relate to my lived experiences, living conditions, and way of life, it’s important for me—and all of us—to center the insight of Natives. (“Natives” is the term a great many people indigenous to the North American continent prefer over “Native American” and so this is the term I use). I highly recommend the Truthout article on the Dakota Access pipeline protest, “How to Talk About #NoDAPL: A Native Perspective,” by queer Native writer and organizer Kelly Hayes.

The author (left) with Aron Ra, activist and president of Atheist Alliance of America.

I encountered an overwhelming feeling of kinship at Standing Rock, with folks of varied racial, tribal, religious, and ethnic backgrounds and of varied nationalities taking up communal space. That isn’t to say that everything was Kumbaya. It would be complete fantasy to think that hundreds upon hundreds of folks entering a space with a wide range of contrasting attitudes, life experiences, and expectations would be able to coexist in perfect harmony. However, the shared goal to thwart the building of an oil pipeline that threatens Native health and life continued to unify those at the camps despite temperatures that approached freezing.

What has unfolded at Standing Rock in a way acts as a microcosm of the way Native welfare, land, and cultural lifestyle have long been subjected to disregard by corporate and government interests.

Though I spent my weeklong visit as a representative of the American Humanist Association (and I proudly stated this fact when donating supplies), my status was inconsequential. I was one of hundreds of outsider bodies. I tried to help in any way possible, and that included going on supply runs, aiding with various menial tasks around the camps, and undergoing direct action training conducted by the Indigenous Peoples Power Project (also known as “IP3”) to be a water protector, the term protesters at Standing Rock have chosen for themselves.

During my direct action orientation, something one of the IP3 trainers said stuck with me:

As we fight against the establishment, we need to make sure we honor and respect each other. In the process of doing this fight, we don’t want to repeat the operating principles of the system of the United States that says it’s okay to disrespect sovereignty, to disrespect what we consider sacred.

The resistance at Standing Rock is both about the Dakota Access pipeline and the oppressive legacy that supports it. The trainer’s words emphasized that at the root of this nation’s “operating principles” is white supremacist colonialism. This coincides with something Hayes stated in her article:

It is crucial that people recognize that Standing Rock is part of an ongoing struggle against colonial violence. The Dakota Access pipeline (#NoDAPL) is a front of struggle in a long-erased war against Native peoples—a war that has been active since first contact, and waged without interruption.

The pipeline (or “black snake” as it’s called by some Natives) nears completion at the expense of defiling a crucial water source, sacred cultural sites, and an entire way of life that opposes colonial coercion.

Three counter arguments to the Standing Rock protest that continue to circulate are: (a) the pipeline doesn’t cross into the Standing Rock Sioux reservation, (b) the tribe had their chance to oppose the pipeline early on but weren’t cooperative with the US Army Corps of Engineers in the early planning stages, and (c), a point nontheists in particular make, we shouldn’t support claims to “sacred” land.

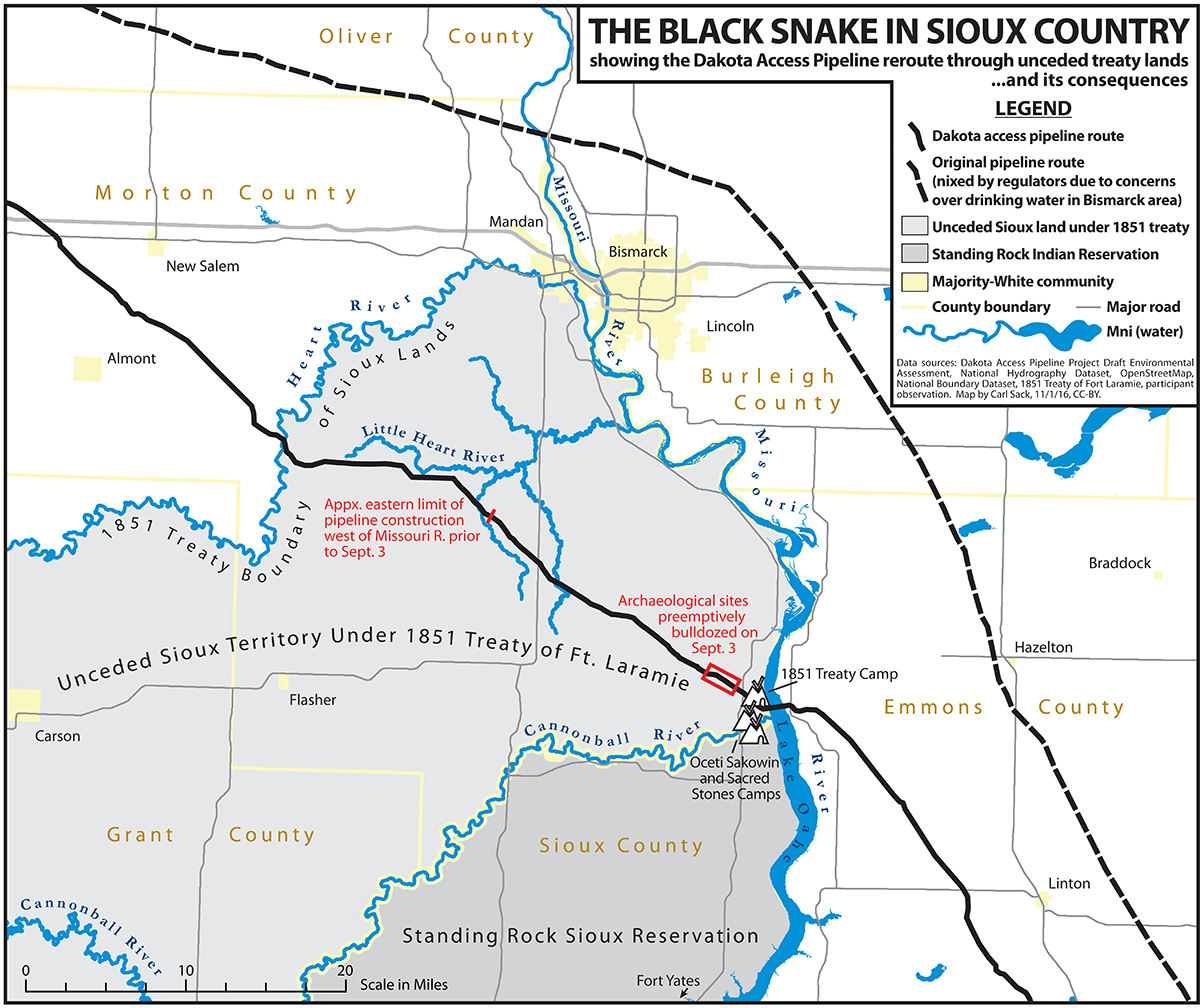

While it’s true that the pipeline doesn’t cut directly into the reservation itself, it does cross through territory that belongs to the Sioux, which directly violates the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie that states the land is reserved for “undisturbed use and occupation” of Native inhabitants.

The claim that Standing Rock tribe members waited too long to object to the $3.7 billion Dakota Access pipeline project turns out to be patently false. Kelcy Warren, CEO of Energy Transfer Partners, the parent company of Dakota Access LLC, told the Wall Street Journal that the pipeline could have been rerouted if the tribe had engaged in discussions sooner. “We could have changed the route. It could have been done, but it’s too late,” Warren said in the interview published November 16.

However, an audio recording from two years ago contradicts Warren’s comments. Recorded on September 30, 2014, and released by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, the audio of a meeting with Dakota Access pipeline representatives reveals the tribe’s opposition to the pipeline and its concerns about potential risks to sacred sites and the water supply.

Aside from this fact, when it comes to what’s perceived as the tribe’s uncooperative nature regarding the pipeline construction, how acquiescent would you be to representatives of a system that had long subverted your culture and your land? I know it’s difficult for some to imagine this viewpoint, but it’s important to consider how social history and cultural context influence our attitudes and behavior. The Standing Rock Sioux tribe argued against these plans for nearly two years before the story received widespread attention. And they stood their ground for good reason, since any leakage issue with the pipeline system would threaten a main source of water for drinking and agriculture supplied to millions.

And let’s not forget that the pipeline is being rerouted through Native territory because the earlier plan to cross the Missouri River north of Bismarck, North Dakota, was deemed a threat to that area’s water supply. Natives are now being forced to endure the desecration of sites sacred to them and are subjected to ecological risks that neighboring white residents rejected.

Lastly, the pipeline’s path runs through an estimated twenty-seven gravesites and eighty-two other artifact sites that hold great cultural significance for the Sioux tribe. The pipeline construction has and continues to disturb these areas. Why should we treat this as trivial just because these locations are explicitly deemed sacred? Do we not consider the gravesites of our deceased loved ones in some sense sacred though we may not use that terminology? Should we withhold concern for distress related to the destruction of cultural heritage because non-Natives are unable to directly identify with the issue?

We inhabit a land that was stripped from Native communities in order to erect a nation that excludes them. What does it say about people’s humanism if they can’t sympathize with the plight and perspective of those whose cultural customs differ from their own?

During my time at the Standing Rock reservation I interviewed a number of people, including a white clergy member named Benjamin Morris, a pastor at Common Ground campus ministry. He and hundreds of other clergy members converged on Cannon Ball to oppose the pipeline construction. I met Morris during a peaceful protest on Backwater Bridge on highway 1806, north of the Oceti Sakowin camp. This was a resistance effort that stood in stark contrast to the confrontation that saw water protectors abused with pepper spray and rubber bullets by a large assembly of militarized police northeast of camp that same day.

I asked Morris why he felt it was important to visit and support the Native tribes’ resistance against the pipeline construction. His response reflected introspection and an ability to decenter himself in preference for those who have endured an unfathomable tradition of marginalization in this country:

I’m here basically as a person of faith to support the people of Standing Rock in their stand against the Dakota Access pipeline. I’m here because the church, for 500 years plus, has been complicit in theft of land and the genocide of Native American peoples both in North and South America and the Caribbean. The church has stood on the wrong side of this for a long time. And so, by showing up, in a small, tiny, miniscule way, I think the clergy who are here are hoping to stand on the right side of history. We believe God is on the side of the oppressed and on the side of the suffering. This is a very big moment in Native American liberation, in a 500-year struggle against colonialism.

I feature Morris’s reflections, despite his non-Native perspective, for two reasons: first, because they show a refreshing level of intellectual honesty and social awareness that prioritizes justice over self-interest, and second, because the implications of his stance echo what the humanist philosophy proclaims to be about.

Sure, humanists lean on human reason and accountability rather than relying on supernatural guidance. Nevertheless, humanism functions as a way to address the wellbeing of life. This level of social concern goes hand-in-hand with both identifying and appropriately responding to forms of injustice that devalue the humanity of any individual or group.

That is why I made the cross-country journey: out of a sense of moral outrage and moral obligation to confront oppressive practices while also aiding those who resist said oppression. My humanism won’t allow me to stand by and be complicit through silence. My humanism won’t allow me to trivialize the significance of this Native resistance simply because the Dakota Access pipeline construction doesn’t directly impact my life.

This brings to mind something a Native activist friend of mine, Taté Walker, wrote recently. Walker is an award-winning Mniconjou Lakota journalist and a citizen of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe. In her probing article for Everyday Feminism, titled “Three Things You Need to Know about Indigenous Efforts against the Dakota Access Pipeline,” Walker writes, “This is about Indigenous resurgence, sovereignty, and resilience. This is about the legacy we leave the next seven generations and beyond. Join us.”

Humanists specifically identify with the term “humanism” for a reason. We believe in human-derived determination of justice and equality rather than divine requital. Standing with Standing Rock is not just a stand against environmental discrimination—but validating and joining together with those who, for centuries, have been dehumanized and have endured the erasure of their very existence.

Photos via Sincere Kirabo

Photos via Sincere Kirabo