The X-Man Effect: When Genetics Catch Up to Human Mutation

I am not a geneticist. In fact, when meeting with scientists at the National Institute of Health (NIH), I often paraphrase Denzel Washington’s famous line from the movie Philadelphia: “alright, explain this to me like I’m a two-year-old because there’s an element to this thing that I just cannot get through my thick head.” No, I am not a geneticist. I am a woman whose son happens to be a genetically unique human being.

Raising a child offers us a chance to study the philosophical nature of humanity, and ourselves up close. What is the definition of a person? Are we born with a moral compass? Of our behaviors, which are the result of nature and which of nurture? When a child is born with a disability, the questions about our humanity dive deeper. What role does language and reason play in defining our humanity? How do we align ethics and maladaptive behaviors? Philosophy may take us part of the way, but only when married with scientific investigation can we really begin to glimpse the answers of who we are.

Fourteen years ago, my son Ian was diagnosed with autism (simply because at that time the doctors had no real idea of what was going on). My evangelical parents told me that his disability was God’s punishment of me, and that I should celebrate this gracious second chance he was giving me and embrace the inspiring lessons he would teach me through my child’s terrible life. After all, God only gives us as much as we can handle.

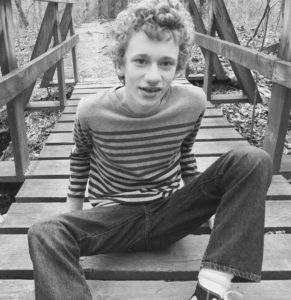

The author’s son, Ian

So, being the good humanist that I am, I ignored all of that ridiculousness and enrolled my son in as many genetic studies at the NIH as I could. I knew that science, not a god, would explain what had happened and what we were facing; scientists, not priests, would teach me what I needed to know in order to support the growth and development of my child. I had no idea that we would solve a mystery or that my son’s genetic composition would end up being the first of its kind ever documented.

Ian is one of sixteen children worldwide with a genetic mutation on the DEAF1 gene. He is one of six children documented in the US. And he is the only one across the globe documented with a specific DEAF1 mutation.

Over the course of the last twelve years, Dr. Seth Berger (MD, PhD, and a medical biochemical genetics fellow) and his colleagues identified six DEAF1 variant pediatric patients with developmental delays and other clinical features of unknown etiology in the US. (They began studying Ian in 2005; they identified the genetic mutation in 2016.) The team of scientists carried out molecular experiments to assess the effects of the small deletions on human DEAF1 function. The results demonstrated that the variants severely affect DEAF1 transcriptional activities, DNA binding, and intracellular localization. Meaning, in the simplest of terms, that the evidence supported the hypothesis that mutations on the DEAF1 gene are the underlying cause of the disabilities in these children.

According to the American Psychiatric Association, intellectual disability (ID) is a common neurodevelopmental disorder that is characterized by varying degrees of cognitive dysfunction and maladaptive behaviors. ID can occur either in isolation or in conjunction with other clinical and physical features and many different types of disabilities include the feature of ID. Four girls and two boys, between the ages of two and fifteen, with DEAF1 mutations participated in an NIH study published in September. These children all turned out to share a number of physical characteristics, including severe ID, motor delay, absent speech, prenatal growth retardation, seizures, hypotonia, ataxia, sleeping problems, hearing loss, and a high threshold to pain. They also shared neurobehavioral abnormalities including autism, aggression, self-injury, mood swings, excessive irritability, frequent infections, feeding difficulties, and digestive abnormalities. (Yes, you read that correctly: a proven genetic cause of aggression, irritability, self-injury, and mood swings). And, perhaps the most relieving study result of all, these DEAF1 mutations were determined to be spontaneous, meaning they were not passed down to the child from either parent.

A human chromosome can have up to 500 million base pairs of DNA with thousands of genes. The DEAF1 gene is just one of some twenty-thousand similar proteins and is important in the regulation of embryonic development. So, it makes sense that even small mutations on this gene would have impressive impacts on human development. Twelve years ago mutations like this were not known to exist; we didn’t have the technology to see them. Twelve years ago the human genome had just been mapped. Fifty years ago, these children were written off as “retarded.” One hundred years ago (and in some places still today), they were believed to be demon possessed. In ancient times, human beings who didn’t have logos (speech or reason) weren’t even considered human.

Science and human understanding have come a long way. Who knows what more we will learn about our own genetic make-up twenty, fifty, or one hundred years from now.

So what’s next for these DEAF1 variant children? What wonderful cure awaits them now that we know exactly what to treat? How will these brilliant scientists unlock their potential?

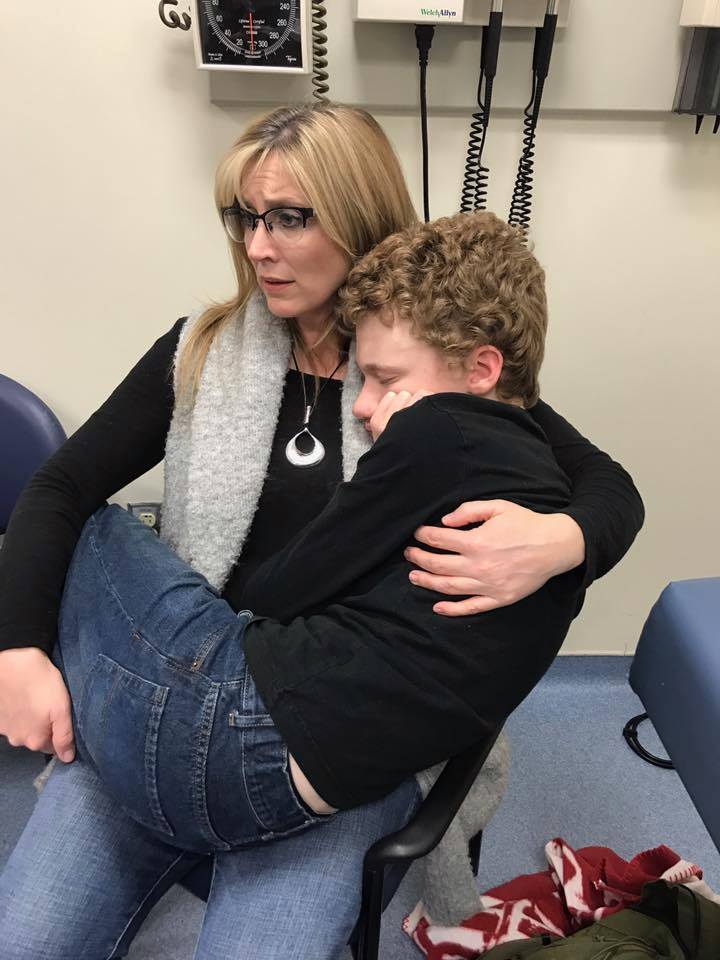

Amy Couch & her son, Ian

More waiting is what’s next. Waiting, again, for the science to catch up, and knowing that it eventually will. As Dr. Berger said to us, this research really doesn’t offer an immediate solution; it instead offers us information that will further the scientific research that might one day offer a treatment. “Studies like this are the first step in understanding how the single random spelling error in DEAF1 can lead to the complex developmental differences seen in children like Ian.”

Maybe it sounds bleak to discover the cause of a child’s disability without having any direct recourse. But it also imbues hope; it is not an unsolvable mystery. My son’s experiences—being the oldest in this study group—offer benefits to the younger children and families affected by similar DEAF1 mutations. They will now know, for example, the impact of the DEAF1 mutation on physical growth and development during puberty. They may learn which seizure medications are most effective as their child’s body changes with age. And as Ian ages, we will gain new insights to share. With knowledge comes power. Ian’s diagnosis may not help him in his lifetime, but it will help those children following in his footsteps and may perhaps provide treatment options to those following generations behind him.

As Neal deGrasse Tyson says, “The good thing about science is that it’s true whether or not you believe in it.” Science has yet to prove that there is a supernatural deity who takes joy in causing infants to be born with severe disabilities just to punish their parents for their wayward lives. Science has proven, however, that some of us are born with genetic mutations that, however miniscule, greatly change the mapping of our DNA and can cause significant alterations in our physical and mental development.

Mutation is the key to our evolution. It has enabled us to evolve into the dominant species on the planet. This process normally takes thousands and thousands of years. But, as Professor Charles Francis Xavier of the X-Men says, every few hundred millennia, evolution leaps forward.

So, let’s be thankful for the gift of information this real group of X-humans has given to humanity, and the very special team of scientists who continue to study them and thus move humanity’s scientific understanding forward. To paraphrase Albert Einstein, we can’t help but be in awe of the mysteries of life and the marvelous structure of reality. And although we can’t know everything at once, perhaps it’s enough just to comprehend a little of this mystery each day.