The Religious Disneyfication of the Harlem Renaissance

Author Nella Larsen

Author Nella Larsen To be African American in the 1920s was hard enough, to be a female author in the publishing industry somewhat more daunting, and to be one who held that religion perpetuated rather than combated the worst excesses of racism was to be in scant company indeed.

Right now, in a hundred book clubs spread across the United States, the literary history of the Harlem Renaissance is being rewritten with a thousand discussion questions of good intent but devastating effect. As a result, a movement that once brimmed over with radical ideas and shuddered before no idol is turning slowly into a sanitized collection of feel-good tales of adversity overcome. Hardest hit are those works that feature stinging portrayals of religion’s role in racism, the legacy of their authors muted in the name of marketability. It’s a vision of the Harlem Renaissance that’s long overdue for correction.

There are a number of female authors in particular who bravely faced up to three-fold discrimination to say their piece, and who have been coldly rewarded for their bravery in our own times. To be African American in the 1920s was hard enough, to be a female author in the publishing industry somewhat more daunting, and to be one who held that religion perpetuated rather than combatted the worst excesses of racism was to be in scant company indeed. And yet, from that handful of authors we have some of the most beautiful, disturbing, and profound works to emerge from the Harlem Renaissance.

The crown jewel of this tradition is, without a doubt, Nella Larsen’s slim marvel of a novel, Quicksand. First published in 1928, it was hailed instantly as a milestone. W.E.B. DuBois dubbed it “the best piece of fiction that Negro America has produced since the heyday of [Charles W.] Chesnutt.” And yet, two years later, on the heels of a groundless plagiarism accusation, Larsen’s career was over as suddenly as it had begun. For the next three decades, she lived in total obscurity, never putting pen to paper again. Her great work, however, has never entirely slipped from common memory; it’s one of those books that, once read, lodges within the wheels of your mind.

The crown jewel of this tradition is, without a doubt, Nella Larsen’s slim marvel of a novel, Quicksand. First published in 1928, it was hailed instantly as a milestone. W.E.B. DuBois dubbed it “the best piece of fiction that Negro America has produced since the heyday of [Charles W.] Chesnutt.” And yet, two years later, on the heels of a groundless plagiarism accusation, Larsen’s career was over as suddenly as it had begun. For the next three decades, she lived in total obscurity, never putting pen to paper again. Her great work, however, has never entirely slipped from common memory; it’s one of those books that, once read, lodges within the wheels of your mind.

Quicksand is the story of Helga Crane, the daughter of a racially mixed couple, whose education and restlessness drive her from misery to misery. Unable to find herself at home under the crippling omnipresent racism of the United States or in the accepting but somber bosom of her mother’s native Denmark, she comes to believe that happiness and companionship are simply things she’ll never know. Then one day, broken by disappointment and drenched by a sudden storm, she finds her way into a small church. In other books this scene would play out as a moment of triumphant salvation, but in Larsen’s masterful hands the grotesquery of the conversion process, the breaking down of the human spirit under false promise, has all of the brutal earmarks of a rape scene:

The yelling figures about her pressed forward, closing her in on all sides. Maddened, she grasped at the railing, and with no previous intention began to yell like one insane, drowning every other clamor, while torrents of tears streamed down her face. She was unconscious of the words she uttered, or their meaning: “Oh God, mercy, mercy. Have mercy on me!” But she repeated them over and over. From those about her came a thunder-clap of joy. Arms were stretched towards her with savage frenzy. The women dragged themselves upon their knees or crawled over the floor like reptiles, sobbing and pulling their hair and tearing off their clothing. Those who succeeded in getting near to her leaned forward to encourage the unfortunate sister, dropping hot tears and beads of sweat upon her bare arms and neck.

Thrown violently out of equilibrium by the “confusion of seductive repentance” (a deliciously apt phrase if ever there was one), Helga convinces herself to marry a Southern preacher who breaks her will and vitality through serial pregnancy, scolding her for lack of faith whenever she complains of the weariness of her worn body. Lingering near death after a failed birth, she finally realizes the insidious role that religion has played in manipulating her race.

The cruel, unrelieved suffering had beaten down her protective wall of artificial faith in the infinite wisdom, in the mercy, of God. For had she not called in her agony on Him? And he had not heard. Why? Because, she knew now, He wasn’t there. Didn’t exist… Life wasn’t a miracle, a wonder. It was, for Negroes at least, only a great disappointment… The white man’s God. And His great love for all people regardless of race! What idiotic nonsense she had allowed herself to believe. How could she, how could anyone, have been so deluded? How could ten million black folk credit it when daily before their eyes was enacted its contradiction?

Small wonder that, impelled by a desire to do justice to the female writers of the Harlem Renaissance, the Oprahs and television networks skipped easily over this small, uncompromising volume, and lighted instead upon the more easily digestible, less rancorous works of Zora Neale Hurston and Dorothy West. Justice, yes, but let’s not alienate any key demographics. (Though I must confess I do unambiguously love West’s The Living is Easy).

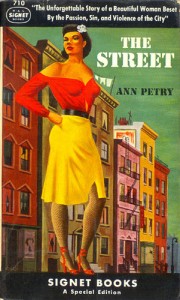

Such thinking also explains the unfathomable lack of interest in reviving the works of Ann Petry. Her debut novel, The Street, was published in 1946 and was the first novel by an African-American woman writer to sell a million copies. And deservedly so. The Street delves into the question of race not from the point of view of politics or personality, but from that of structure, a penetrating look into how the physical realities of living and working space, perpetuated over half a century, succeeded in diverting an entire racial group into an inescapable spiral of urban hopelessness. It is a challenging book that doesn’t settle for easy resentment or racial slogan-smithing, and its portrayal of religion is completely dismissive. God is a hypothesis that Petry has no need for. His only appearance is in the form of a golden cross that one of the characters nails above her bed to act as a talisman to prevent her lover from walking out on her. It is a fetishistic object bought from a witch doctor that only works because of the superstitious paranoia it engenders. Beyond that, there is nothing any supernatural power can do to alleviate the crushing weight of place and time.

Such thinking also explains the unfathomable lack of interest in reviving the works of Ann Petry. Her debut novel, The Street, was published in 1946 and was the first novel by an African-American woman writer to sell a million copies. And deservedly so. The Street delves into the question of race not from the point of view of politics or personality, but from that of structure, a penetrating look into how the physical realities of living and working space, perpetuated over half a century, succeeded in diverting an entire racial group into an inescapable spiral of urban hopelessness. It is a challenging book that doesn’t settle for easy resentment or racial slogan-smithing, and its portrayal of religion is completely dismissive. God is a hypothesis that Petry has no need for. His only appearance is in the form of a golden cross that one of the characters nails above her bed to act as a talisman to prevent her lover from walking out on her. It is a fetishistic object bought from a witch doctor that only works because of the superstitious paranoia it engenders. Beyond that, there is nothing any supernatural power can do to alleviate the crushing weight of place and time.

Petry wrote her last novel, The Narrows, in 1953, and in it allowed herself much more explicit statements about how religion interferes with basic decency. The central story of the book revolves around a romance between an African-American male and a white female, both of whom combine unreflecting selfishness with overwrought erudition to an unappealing degree that would wreck the novel were it being written by less of a master than Petry. Fortunately, as in The Street, Petry spends large swaths of the book focusing on the side stories of her secondary characters with a faultless eye for psychological detail. Chief among these is Abbie Crunch, adoptive aunt of the lead male, a woman whose default approach to life is righteous indignation rather than open compassion.

Author Ann Petry

When Abbie’s husband is brought unconscious into her home by the local bartender, she assumes that he has drunk himself senseless in spite of the bartender’s insistence to the contrary. In a pique of high moral outrage, she spreads newspapers on the floor and dumps his convulsing, seizure-wracked, body on top of them, refusing everybody’s advice to call a doctor until it is too late for anything to be done. It is not the last time that her instinct towards outrage will end in tragedy.

Faced with a tearful Jewish mother complaining about how the Christians at school were taunting her son with chants of “matzos, matzos, two for five, that’s what keeps the kikes alive,” Abbie decides to hotly deny that such things could possibly have been learned in Sunday school rather than to actually comfort the distraught human being in front of her. Repeatedly throughout the book, her attachment to religious purity prevents her from extending a helping hand to suffering people, breeding unnecessary tragedy. From Abbie Crunch to a priest who simply walks on by while a young man is being unjustly beaten by the police to the garish self-aggrandizement of the local preacher who installs mega-speakers in his church to inflict his views upon the neighborhood, the message of The Narrows is that decency and understanding are astoundingly rare creatures who cannot breath in the thick, inhumane atmosphere of theology.

Ironically, The Narrows also carries Petry’s own epitaph. One of the characters explains about church membership:

When they’re young they don’t go to church. Then when they gets false teeth and they waterworks run all the time, they gets scared, they think that well, after all, everybody’s got to die some time and so mebbe they could, too… Then one mornin’ they gets up and looks in the mirror and they got gray hair and a bald spot and they kind of adds themselves up, and they got a full set of uppers and lowers and two sets of glasses and some kind of funny crick in the middle of they backs and they begin to figure mebbe they better start goin’ to church.

Petry would, in her sixties, have such a moment herself, and among her last published works is a children’s book about the lives of the saints. Still, it in no way detracts from the portrayal of religion in her novels as a force of superstition and inhumanity lined up against the best instincts of humanity.

By omitting Petry and Larsen from the pantheon of female Harlem Renaissance authors (though Petry is admittedly something of a latecomer), the recent popularizers of the movement have cut away a large chunk of its vital force. Deciding ahead of time that the only authors due for revival would be those with uplifting messages about diffuse spirituality and self-belief that would play well on television, they have only perpetuated long-lived stereotypes about religiosity and race. These stereotypes are not only inaccurate, but do active harm to thousands of young adults afraid to admit their own lack of belief for fear that it will cut them off from their culture and heritage. Far better to demonstrate the vitality of the Harlem Renaissance in all of its shades by resisting the urge to cherry-pick its authors. Then those people struggling to come to grips with their humanism will have at long last some predecessors to look to, a feeling of common cause, and an understanding voice from the deep recesses of the past to assure them that they are not as alone as they feel.