How to Be a Wise Guy or a Wise Girl

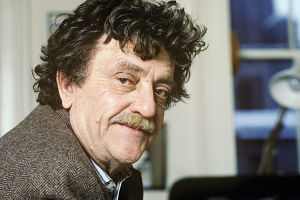

This speech, originally delivered to the graduating class of Southampton College on June 7, 1981, is excerpted from If This Isn’t Nice, What Is? The Graduation Speeches and Other Words to Live By, (Much) Expanded Second Edition by Kurt Vonnegut, edited by Dan Wakefield (2016). Reprinted with permission of Seven Stories Press.

THIS SPEECH CONFORMS to the methods recommended by the United States Army Manual on how to teach. You tell people what you’re going to tell them. Then you tell them, then you tell them what you told them.

Now we’ll first discuss honorable behavior, especially in peacetime, and we’ll then comment on the information revolution—the astonishing fact that human beings can actually know what they’re talking about in case they want to try it. From there, I will go on to recommend to those graduating from colleges everywhere in the world this spring that their hero be Ignaz Semmelweis.

You may laugh at such a name for a hero, but you will become most respectful, I promise you, when I tell you how and why he died.

After I describe Ignaz Semmelweis a little, I will ask if he might not represent the next stage of human evolution. I will conclude that he had better be. If he doesn’t represent what we’re going to become next, then life is all over for us and for the cockroaches and the dandelions too.

I will give you a hint about him. He saved the lives of many women and children. If we continue on our present course there will be less and less of that going on. OK.

Now we come to the main body of the speech, which is an amplification of the first part. See how memorable it all becomes. No wonder we have the greatest Army in the world. Honor. I have always wanted to be honorable. All of you want to be honorable too, I’m sure.

A lot of the talk about honor in the past has had to do with behavior on the battlefield. An honorable man holds his country’s flag high even though he is as full of arrows as St. Sebastian. An honorable little drummer boy drums and drums and drums rat-a-tat-tat, rat-a-tat-tat till he has his little head blown off.

General Haig should really be here to talk about that sort of honor. I was only a corporal. Modern weapons, of course, have made that sort of honor even scarier than it used to be.

A person in control of missiles and nuclear warheads could behave so honorably as to get everybody killed. The whole planet could become like the head of the brave little drummer boy rolling off into a ditch somewhere.

So I will limit my discussion to honorable behavior in peacetime situations. In peacetime it is honorable to tell the truth to those who deserve to hear it.

You guarantee that you are telling the truth by saying I give my word of honor that such and such is true. I have never knowingly lied, having said first I give my word of honor. So I now give you my word of honor that it is a courageous and honorable and beautiful thing you have done to become college graduates.

I give you my word of honor that we love you and need you. We love you simply because you are of our species. You have been born. That is enough.

We need you because we hope to survive as a species, and you are in possession of or can get possession of solid information which, properly understood and put to use, can save us as a species.

I give you my word of honor as the adult version of “cross my heart and hope to die.’’ We are drawing ever closer to Ignaz Semmelweis, in case you’re wondering what on earth happened to him. Just be patient. Most of you, if not all of you, feel inadequately educated. That is an ordinary feeling for a member of our species. One of the most brilliant human beings of all times, George Bernard Shaw, said on his seventy-fifth birthday or so that he knew enough at last to become a mediocre office boy. He died in 1950, by the way, when I was twenty-eight, about ten years before most of you were born.

He would envy you now. He would envy your youth, surely. Perhaps you all know what he said about youth, that it was a shame to waste it on the young.

But he would be even greedier for the solid information which you have or can get about the nature of the universe, about time and space and matter, about your own bodies and brains, about the resources and vulnerabilities of our planet, about how all sorts of human beings actually talk and feel and live.

This is the information revolution I promised to tell you about. We have taken it very badly so far. Information seems to be getting in the way all the time. Human beings have had to guess about almost everything for the past million years or so. Our most enthralling and sometimes terrifying guesses are the leading characters in our history books. Should I name two of them? Aristotle and Hitler. One good guesser and one bad one.

If you haven’t heard of them by now, this is a bust of a graduation. And the masses of humanity having no solid information have had little choice but to believe this guesser or that one. Russians who didn’t think much of the guesses of Ivan the Terrible, for example, were likely to have their hats nailed to their heads.

Let us acknowledge, though, that persuasive guessers, even Ivan the Terrible, now a hero in the Soviet Union, have given us courage to endure extraordinary ordeals which we had no way of understanding. Crop failures, wars, plagues, eruptions of volcanoes, babies being born dead—they gave us the illusion that bad luck and good luck were understandable and could somehow be dealt with intelligently and effectively.

Without that illusion, we would all have surrendered long ago. The guessers, in fact, knew no more than the common people and sometimes less. The important thing was that somebody gave us the illusion that we’re in control of our destinies.

Persuasive guessing has been at the core of leadership for so long for all of human experience so far that it is wholly unsurprising that most of the leaders of this planet, in spite of all the information that is suddenly ours, want the guessing to go on.

It is now their turn to guess and guess and be listened to.

Some of the loudest, most proudly ignorant guessing in the world is going on in Washington today. Our leaders are sick of all the solid information that has been dumped on humanity by research and scholarship and investigative reporting.

They think that the whole country is sick of it, and they could be right. It isn’t the gold standard that they want to put us back on; they want something even more basic than that. They want to put us back on the snake-oil standard again.

Loaded pistols are good for people unless they’re in prisons or lunatic asylums. That’s correct. Millions spent on public health are inflationary. That’s correct. Billions spent on weapons will bring inflation down. That’s correct. Dictatorships to the right are much closer to American ideals than dictatorships to the left. That’s correct. The more hydrogen bomb warheads we have all set to go off at a moment’s notice, the safer humanity is, the better the world our grandchildren will inherit. That’s correct.

Industrial wastes and especially those which are radio-active hardly ever hurt anybody, so everybody should shut up about them. That’s correct.

Industries should be allowed to do whatever they want to do. Bribe, wreck the environment just a little, fix prices, screw dumb customers, put a stop to competition and raid the Treasury in case they grow broke. That’s correct. That’s for enterprise. That’s correct.

The poor have done something very wrong or they wouldn’t be poor, so their children should pay the consequences. That’s correct. The United States of America cannot be expected to look after its people. That’s correct. The free market will do that. That’s correct. The free market is an automatic system of justice. That’s correct.

And if you actually remember one-tenth of what you’ve learned here, you will not be welcome in Washington, DC. I know a couple of bright seventh graders who would not be welcomed in Washington, DC. Do you remember those doctors a few months back who got together and announced that it was a simple, clear medical fact that we could not survive even a moderate attack by hydrogen bombs? They were not welcome in Washington, DC.

Even if we fired the first salvo of hydrogen weapons and the enemy never fired back, the poisons released would probably kill the whole planet by and by.

What is the response in Washington? They guess otherwise. What good is an education? The boisterous guessers are still in charge—the haters of information. And the guessers are almost all highly educated people, think of that. They have had to throw away their education; even Harvard or Yale education.

If they didn’t do that, there is no way their noninhibited guessing could go on and on and on. Please, don’t you do that. And I give you something to cling to; for if you make use of the vast fund of knowledge now available to educated persons, you are going to be lonesome as hell. The guessers outnumber you and now I have to guess about ten to one.

Commemorative plaque of Ignaz Semmelweis in Budapest

The thing I give you to cling to is a poor thing, actually.

Not much better than nothing, and maybe it’s a little worse than nothing. I’ve already given it to you. It is the idea of a truly modern hero. It is the bare bones of the life of Ignaz Semmelweis. My hero is Ignaz Semmelweis. You may be wondering if I’m going to make you say that out loud again. No, I’m not, you’ve heard it for the last time.

He was born in Budapest in 1818. His life overlapped with that of my grandfather and with that of your great-grandfathers and it may seem a long time ago to you, but actually he lived only yesterday.

He became an obstetrician, which should make him modern hero enough. He devoted his life to the health of babies and mothers. We could use more heroes like that. There’s damn little caring for mothers or babies or old people or anybody physically or economically weak these days as we become ever more industrialized and militarized with the guessers in charge.

I have said to you how new all this information is. It is so new that the idea that many diseases are caused by germs is only about 120 years old.

The house I own out here in Sagaponack is twice that old. I don’t know how they lived long enough to finish it. I mean the germ theory is really recent. When my father was a little boy, Louis Pasteur was still alive and still plenty controversial. There were still plenty of high-powered guessers who were furious at people that would listen to him instead of to them. Yes, and Ignaz Semmelweis also believed that germs could cause diseases. He was horrified when he went to work for a maternity hospital in Vienna, Austria, to find out that one mother in ten was dying of childbed fever there.

These were poor people—rich people still had their babies at home. Semmelweis observed hospital routines, and began to suspect that doctors were bringing the infection to the patients. He noticed that the doctors often went directly from dissecting corpses in the morgue to examining mothers in the maternity ward. He suggested as an experiment that the doctors wash their hands before touching the mothers.

What could be more insulting. How dare he make such a suggestion to his social superiors. He was a nobody, he realized. He was from out of town with no friends and protectors among the Austrian nobility. But all that dying went on and on and Semmelweis, having far less sense about how to get along with others in this world than you and I would have, kept on asking his colleagues to wash their hands.

They at last agreed to do this in a spirit of lampoonery, of satire, of scorn. How they must have lathered and lathered and scrubbed and scrubbed and cleaned under their fingernails. The dying stopped—imagine that! The dying stopped. He saved all those lives.

Subsequently, it might be said that he has saved millions of lives—including quite possibly yours and mine. What thanks did Semmelweis get from the leaders of his profession in Viennese society, guessers all? He was forced out of the hospital and out of Austria itself, whose people he had served so well. He finished his career in a provincial hospital in Hungary. There he gave up on humanity, which is us, and our knowledge, which is now yours, and on himself.

One day in the dissecting room, he took the blade of a scalpel with which he had been cutting up a corpse, and he stuck it on purpose into the palm of his hand. He died, as he knew he would, of blood poisoning soon afterward.

The guessers had had all the power. They had won again. Germs indeed. The guessers revealed something else about themselves too, which we should duly note today. They aren’t really interested in saving lives. What matters to them is being listened to—as however ignorantly their guessing goes on and on and on. If there’s anything they hate, it’s a wise guy or a wise girl.

Be one anyway. Save our lives and your lives too. Be honorable. I thank you for your attention.