Rules Are for Schmucks: Conscientious Objection and Abortion

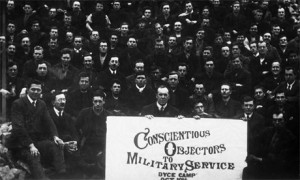

A crowd of conscientious objectors to military service during the first world war. Photo: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis

A crowd of conscientious objectors to military service during the first world war. Photo: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis There are certain rare situations where it makes sense for the law to bend a little to accommodate a deeply held moral belief. One such instance involves the military draft. Some people simply will not fight because they believe it is morally wrong; imprisoning or executing these people has not always seemed to be the best response.

The history of government accommodation of conscientious objectors goes back hundreds of years. In most cases, the legal right to avoid fighting required the sanction of organized religion to be valid. One of America’s most famous objectors, Sergeant York, responded to paperwork asking, “Do you claim exemption from the draft (specify grounds)?” by writing simply “Yes. Don’t Want To Fight.” But his independent backwoods church wasn’t recognized as an official denomination promoting pacifist beliefs (like the Quakers), so his application was denied. Ultimately, he dropped the issue when a recruiter persuaded him that the Bible was all in favor of killing enemies who deserved it, which he proceeded to do with uncanny skill.

America’s other famous conscientious objector was Muhammad Ali, who took his case all the way to the Supreme Court. According to Bob Woodward’s book The Brethren, the real issue in this case was whether his Black Muslim religion was sufficiently legitimate to justify his refusal to serve.

By contrast, in World War I Britain, the standard for conscientious objection had nothing to do with religion. As Adam Hochschild describes in To End All Wars, anyone with a strong moral objection to war, whether religious or secular, could avoid combat service. Aside from being fairer to nonbelievers, this approach also frees courts from the messy business of wrestling with questions of theology, as the Supreme Court had to do in Ali’s case.

Most crystal balls say it’s unlikely we’ll have to deal with conscientious objection to the military draft again, but the experience of conscientious objectors to the draft sheds light on some similar issues facing us today.

Last month two Scottish midwives lost a case before the UK Supreme Court, in which they conscientiously objected to doing part of their jobs—the part that involved enabling women to have abortions. Earlier last year, a doctor who runs a hospital in Poland made headlines when he was fired for refusing to perform an abortion.

Just as there are people who deeply believe it is morally wrong to fight wars, there are people who deeply believe it is morally wrong to terminate a pregnancy under most if not all circumstances. In both cases, much of that belief stems from the teaching of God experts. But not all of it. There is, in fact, a group out there called Secular Pro-Life, which is just what its name implies. They strongly disagree with the Catholic Church on contraception, but they march arm-in-arm with the church in its campaign to overturn Roe v. Wade.

So what should be done about medical professionals who say, “I don’t care whether abortion is legal or not—I just find it so distasteful that I don’t want to do it”? Would society work better if we respond, “In that case, you’re kicked out of the profession—try selling shoes instead”? Or would it be better to work out some kind of accommodation, as was done with those who objected to combat service? It seems likely that there are some fine professionals who can provide wonderful service to women who fall in the abortion-objection camp, and just discarding them makes little sense.

Here’s where the Glasgow and Poland cases get tricky. In both countries, the law actually has exactly such an accommodation in place. No medical professional has to dirty his or her hands ending a pregnancy. But the problem, here as elsewhere, is the unyielding legalism of the Catholic Church.

As Paul Blanshard first described sixty-five years ago, the church and its lawyers push everything to the maximum, given the circumstances they’re in. Where they can ban contraception outright, as in 1940s Massachusetts, they do it. Where they can’t achieve that but can at least prevent poor women from getting access to it, as in today’s Philippines, they do that instead. Where they can prevent every woman from deciding whether to continue her pregnancy to term, as in many states in Mexico, they do so. Where they can’t go that far, they throw up every roadblock they can, from waiting periods to parental consent rules to picket lines. The single-minded goal is not to make an always difficult process work more sensibly, but just to cut the number of abortions any way they can.

So, when they see a conscientious objection loophole, they try to drive a truck through it. The midwives in Glasgow were not ordered to go into an operating room and help perform an abortion. They were supervisors—all they were asked to do was to schedule other personnel to assist with lawful procedures. The church, in its obsession with driving down the number of abortions, persuaded these women that doing even that was against God’s will. But the UK court analyzed the job responsibilities and staffing procedures at the hospital and concluded that it could not carry out is function with supervisors who refused to supervise.

Similarly, the doctor in Warsaw could have complied with the law by declining to perform the procedure himself, and referring the woman to another doctor instead. This he refused to do, in line with the cut-the-numbers-at-all-costs mentality. In this particular case, the pregnant woman was not a careless teenager, but a married woman who very much wanted to have a baby. Late in the game, she learned that her baby was missing half its head, and had not the slightest chance of surviving more than a few miserable weeks after birth. But instead of telling her about all her options, as required by law, the doctor simply gave her the address of a hospice where the child could be given “palliative care”—i.e., morphine—until he or she expired. He also was found to have ordered unnecessary tests to make sure the pregnancy passed the twenty-fourth week, after which Polish law made abortion illegal. Not knowing where else to turn, the anguished woman did bear the child, who died right on schedule. That doctor wouldn’t be working in any hospital I have any say over (or any shoe store, for that matter).

Rights to conscientious objection need to be rare, unrelated to the supernatural, and applied in a manner that places first priority on the mission society has chosen to be important, whether it’s winning a necessary war or putting individual women in charge of their own pregnancy decisions.