Ethical Dilemma: Humanist Origins of Nonviolence

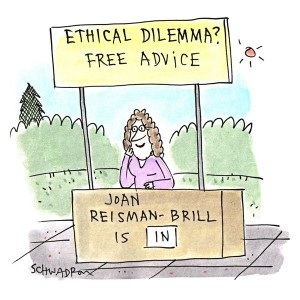

Experiencing an ethical dilemma? Need advice from a humanist perspective?

Send your questions to The Ethical Dilemma at dilemma@thehumanist.com (subject line: Ethical Dilemma).

All inquiries are kept confidential.

Peaceful Without God: First, thank you for your answer to the question about the difference between the words humanism and secular. I have not yet declared myself as a humanist, and your discussion helped me to understand more clearly how I think and feel about completely leaving Christianity, the religion of my youth.

Through the years I have become more interested in the concept, lifestyle, and activism based on nonviolence. I’ve researched this but found very little written on nonviolence from a humanist perspective (unless I have overlooked some authors). Many nonviolence activists have Christian connections, and would like very much for others joining to believe as they do: that nonviolence comes from a belief in the God and Jesus of peace.

However, my interest in and devotion to peace and nonviolence does not come from a belief in God or Jesus. I’m attempting to realize where my concern for others begins so that I will be comfortable expressing my commitment to helping others, without feeling an obligation to join/obey any particular religion. Is there anything you could write on this that could assist me and others who want to live in a peaceful world and want to participate in the peace movement in order to get there? I can work with others of all faiths, but want to feel secure within myself that I have a right to my beliefs and that how I see things doesn’t come from gods or similar thinking.

—Do I Need Higher Authority To Endorse Peace?

Dear Peace,

First I’d like to share with you some history of anti-war activity in the humanist movement, provided by the American Humanist Association’s Fred Edwords:

During the Vietnam War era, when military conscription (the draft) was in place, the AHA worked together with the American Ethical Union to establish the legal right of nontheistic individuals to apply for and receive conscientious objector status so as to be exempted from military service. The effort succeeded, and will apply again in the future should the draft ever be reinstated. It is worthy to note that, prior to this legal effort, pretty much only Quakers and Mennonites could secure an exemption from military service—all the atheists were in foxholes!

An exception to the above were those humanists and atheists who were willing to go to prison to avoid military service. I knew one humanist who had done prison time to avoid military service during World War II. Humanists are therefore every bit as capable as others of having firm anti-war views.

Stepping back a little further in time, in 1939, a group of Quakers who came to realize they no longer believed in a god, departed from the Society of Friends to form the Humanist Society of Friends. This organization adopted the Humanist Manifesto of 1933 as its official position, but specified that one of its goals was “to oppose war.” Under my guidance, the Humanist Society of Friends joined the AHA family of organizations in 1991 and continues today under the name the Humanist Society, being the celebrant arm of the AHA’s activism, providing humanist officiants, celebrants, and chaplains across the country. Although opposition to war isn’t a position required of all celebrants certified by the Humanist Society, the Humanist Society, as well as the AHA’s Appignani Humanist Legal Center, will vigorously defend the legal right of individual humanist activists to take such a position as their expression of humanism.

And among those humanists unwilling to take an uncompromising stand against war, the overwhelming tendency is toward a position that regards the hurdle of justification to be a high one and the “rules of engagement” to be stiff and precise. Roman Catholic “Just War Theory” isn’t good enough. There have been articles in the Humanist magazine that have advocated this view over the years. And under my editorship of that publication, I ran articles in strong opposition to both the Gulf War and sending troops to Afghanistan.

If one wishes to reach back further, consider a short story that is a staple of anti-war activism, Mark Twain’s “The War Prayer.” Twain was an out-and-out atheist and pacifist.This isn’t to say that there aren’t humanists in the military. There are. We humanists are a diverse lot and cherish not only our freedom of conscience but our right to disagree with each other on critical applications of our philosophy.

And let’s not forget philosopher Bertrand Russell, who continues to be admired by humanists worldwide. He preferred to call himself a rationalist but wrote sardonically to Edwin H. Wilson of the AHA that if somebody called him a humanist he wouldn’t file suit for defamation.

Russell was a famous agnostic pacifist. He served time in jail in Britain for opposing World War I. There is a famous photo of him participating in a 1960s anti-war sit-in. And he and his good friend Albert Einstein issued the “Russell-Einstein Manifesto.” It’s the document that actually began the modern anti-war movement. It led immediately to the Pugwash conferences, first convened by Canadian humanist industrialist Cyrus Eaton. The ringing words of the Russell-Einstein Manifesto, as it called for a banning of “weapons of mass destruction” and a willingness of East and West to set aside their Cold War ideological differences in the interest of global survival, were, “Remember your humanity and forget the rest.”

In the light of this, I have the daring to say that Christianity is by no means a signal promoter of pacifism. Its history of ancient Roman military service, followed by medieval religious warfare (the Crusades, the Papal Inquisition, and the Reconquista of Spain, followed by the conquest of the Americas) exempt it from serious consideration as a historical force for peace in the world. The oft-cited Francis of Assisi was hardly a typical representative of the faith.

Thank you, Fred! Now my input:As someone who’s never been Christian and for a long time has been humanist (even before I’d ever heard the term), from my perspective Jesus and other religious authority figures and doctrines are at least as often a rationale for propelling war and violence as an inspiration for nonviolence. Whether it’s wiping out entire nations that have other beliefs, or attacking individuals of different faiths or none—both of which go back to ancient times and continue to persist today—there’s hardly a conflict you can scratch without finding some religion close to the surface, as a motivation or excuse. How many people wage war vs. seek peace in Jesus’s or other religious figures’ names? I don’t have statistics, but I know the numbers for each are staggering.

I share the view of scientist Steven Weinberg on religion: “With or without it you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion.” I also believe good exists independent of, and predates, any gods.

That is not to say religious organizations don’t do good or promote nonviolence—many of them certainly do. But so do many secular organizations. I don’t believe the good done in the name of religious organizations, including working toward understanding and peace across groups in conflict, is any different from that of secular ones. In either case, it’s really about people who want to work together to improve humanity, whether it’s in the name of God or good, religion or humanism, or something else (e.g., a gut-level aversion to violence).

One advantage religions have going for them is in the sheer number of people affiliated with established structures (physical and organizational), facilitating members’ ability to unite effectively for causes, be they peaceful or otherwise. In contrast, humanist organizations are not nearly as widespread, large, rich, disciplined, or populated with devoted members (although they are growing!), so it’s an uphill battle for humanists and other nonreligious organizations to mobilize people for specific purposes, although there is progress being made on that front.

But even taking into account the lack of visibility and clout of humanist groups, I can’t come up with any instances of humanists banding together to attack other individuals or groups (other than verbally, on occasion). Humanism doesn’t entail any doctrines dictating politics, or physical or other punishments (e.g., execution, torture, excommunication). Devoted to reason, empathy, and the idea that we are all humans with equal claim to human rights, humanists seek to understand differences and resolve them peaceably. Whenever possible, we take a “live and let live” rather than a “my way or no way” approach to disagreements. There are no humanist armies or militias, just occasional (peaceful) gatherings in the name of reason and compassion—including the aptly named Reason Rally.

That said, nothing says humanists are pacifists. I expect many humanists, while generally opposed to wars, torture, and myriad forms of punishment and coercion, would consider certain exceptions, such as to combat hate groups and terrorists. But for most, that would be a last resort, not a first response.

Right now, because specifically humanist organizations are relatively few, small, and scattered, we don’t see a lot of movements branded as humanist. But humanist and nonreligious organizations such as the AHA are growing by leaps and bounds (along with people identifying as nonreligious), and it will not be surprising to see groups emerge in the near future that are specifically dedicated to working for peace under the humanist umbrella. Meanwhile, there are many secular peace groups, which have no overt or covert religious agendas. I hope you will continue your admirable work for peace through one or more of those.