Isaac Asimov and “The Last Trump”

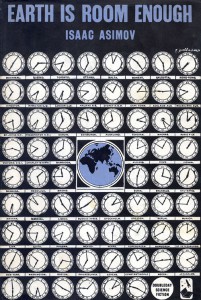

Published in 1957, Earth is Room Enough is a collection of short stories by America’s greatest science fiction writer and former president of the American Humanist Association, Isaac Asimov. This is no arbitrary collection. A single theme runs through all of the works gathered in the book, namely the futility of unrealistic human aspiration—whether in religion or science.

Asimov takes the deepest hopes of the human heart, hopes intricately tied to our deepest fears, and explores the salvation of humankind from its imperfect condition by means both religious and scientific. The stories are full of Asimov’s typically dry humor and help us better understand why, despite the many imperfections of human existence, Earth is room enough. The tile isn’t aimed against the goal of human space colonization (something Asimov deeply favored), but rather suggests that flights of fancy that seem to hold out the promise of resolving humanity’s deepest problems may well give birth to unexpected terrors. Asimov’s stories are warnings in the form of utopian thought experiments that demonstrate just how undesirable some of our religious or scientific ambitions may be.

Allow me to focus on four exemplary stories from the collection: “The Dead Past,” “Living Space,” “Gimmicks Three,” and “The Last Trump.” Each takes an ambitious, utopian premise, ceteris paribus, and tries to follow it to a logical conclusion, one that happens to be rather frightening.

“The Dead Past” holds out the allure of time-viewing as a mechanism with which to better understand history. One of the story’s subplots focuses on academic freedom of scientific investigation, painting a world wherein scientists are held back by a vast administrative system, but also illustrating why and how this system developed to make science more effective over the long run. The time-viewing apparatus at the heart of the story quickly goes from being a useful and amazing resource into being a curse that blots out all privacy in our world by making it possible for anyone to revisit anyone else’s recent past. The machine also opens up a tormenting possibility: it allows us to re-watch the tragic death of loved ones and therefore makes psychological closure almost impossible. As the saying goes, “Time heals all wounds.” Yet, if science holds out the possibility of reopening old wounds at our leisure, there will be no healing.

“Living Space” explores the concept of alter-dimensional travel, which allows human beings to enjoy a life of abundance where each individual working on Earth is able to use a machine that transports them home at the end of the day to an alternate Earth where life had failed to develop. Humans have built sprawling estates for themselves on these uninhabited Earths, and the new middle-class norm is basically one family-one planet.

Because there will always be a finite number of human beings and an infinite number of planets, the problem of population limits and scarcity is solved. However, the very same probabilities and technologies that allow for complacency in the face of population growth also present a grave threat. Sooner or later, humans will run into other humans from alternative timelines. Asimov presents such an encounter in the form of a menacing prospect: an alternative humanity ruled by a victorious Nazi Germany which itself has developed the capacity for alter-dimensional travel. The threat doesn’t stop there. While it’s possible to negotiate alter-dimensional treaties with Germans, things become far more perilous when alter-dimensional aliens show up. The suggestion is clear: Asimov believes it’s folly to ignore Malthus and what the biologists point to as natural limits of population growth.

“Gimmicks Three” is a delightful little story written in the tradition of Goethe’s Faust and CS Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters. The hero of the tale makes a pact with the devil in order to secure a happy earthly existence at the risk of hell (albeit not necessarily as a victim of hell, for a demon offers our hero employment in Satan’s ranks if he is able to use one of the powers gained from his contract in order to solve a problem at the end of his happy earthly life). Asimov’s take on the old “deal with the devil” is unique insofar as the “demonic power” our hero gains is reason, and the use of reason is what helps him defeat the demon, travel back in time, and—having returned to the status quo—resume his life of success at work and a good family life, preferring to trust in God rather than the devil.

Asimov’s story hints at the contradictory nature of the religious concept of demonic temptation. The devil is only able to tempt because he supposedly has the power to influence our wild fantasies. Yet since God is omnipotent and the cause of all things, nothing the devil does actually happens without God at least allowing it. As soon as our hero realizes this, he simply shifts his loyalty from the powerless demon to the all-powerful God. This leaves readers wondering: perhaps there is no moral difference between serving the devil and serving God. An omnipotent God, Asimov seems to suggest, is just a better devil.

Finally, “The Last Trump” is a rather sorrowful account of the resurrection of the dead and one angel’s valiant attempt to stop the end of the world (although Asimov demonstrates his knack for intertwining the melancholic with the comedic). He takes a very literal interpretation of the dead rising from their graves in spiritual bodies that are perfectly physical but also unbound by the limits imposed by biology. So while individual humans no longer slowly diminish and die, they also no longer develop and grow. A couple whose baby died find their child restored, but the baby will never grow into a boy, let alone a man. The parents are stuck with an infinite infant. A businessman whose father and grandfather return to the world of the living is suddenly confronted with a property dispute as both men argue that their wills are null and void and that they should now be in charge of the factory.

Asimov litters his story with a large quantity of simple, day-to-day practical examples of how our wildest hope (resurrection and eternal life) may in practice become a waking nightmare. Of course, one could argue that Asimov doesn’t go far enough: he doesn’t show us the final judgement or heaven. In fact, the process of the resurrection is actually cut short by an angel who manages to find a technicality in Catholic dogma and convince God to return things to the status quo. Once readers realize things are back to the way they were, they no doubt feel an odd sense of relief that human beings are, after all, mortal. In the process of the story, Asimov hints at the intricate relation between good and evil, as the dynamic between God and the devil is demonstrated to be a sort of Hegelian dialectic between negation and positive action wherein both are dependent upon one another in the absolute scheme of things.

All of the short stories collected in this book follow a similar pattern. By trying to envision the fulfillment of our utopian fantasies, Asimov demonstrates the real constraints of human nature. He therefore seems to invite readers to think realistically about both science and religion and, above all, about human psychology. The book explores both the dangers of projecting our fantasies and fears onto mystical gods defined by power as well as the dangers of seeing ourselves as gods whose mastery of science has made us all powerful. One could argue that Asimov is missing the religious notion of God as love in his theology and missing the human virtue of empathy in his presentation of humanity as principally self-interested, barely managing to avoid a war for resources. However, to accuse Asimov of amoral positivism would miss the great moral effect of his portrayal of human beings. By presenting them as they are, even going so far as to exaggerate their short-sighted self-interest and the possibility of utopian fulfillment, Asimov seems to be inviting us to conclude that any conversation about human morality must take into account human reality. It is this realism that is Asimov’s greatest contribution to moral thought.