Take a Selfie with the Bible at Washington’s Newest Attraction

The new Museum of the Bible in Washington, DC (Photo by Alan Karchmer)

The new Museum of the Bible in Washington, DC (Photo by Alan Karchmer) It looms three blocks south of the National Mall in Washington, DC, and features 3,100 items displayed in 430,000 square feet of floor space, two restaurants, a gift shop, a rooftop garden, a ballroom for up to 420 banqueters, and a 472-seat performing arts auditorium. This is the half-billion dollar Museum of the Bible, which opened to large crowds on Saturday, November 18, and has been staging the Broadway musical, Amazing Grace, since November 14.

Seven years in the making, the Museum of the Bible has received significant publicity because of what it contains: a mass of biblical and other historic texts, including one of the world’s largest collections of Torah scrolls; a range of archaeological artifacts; works of art depicting biblical themes; and a selection of items to reflect the Bible’s expansive cultural influence. But in the ramp up to the museum’s opening, serious questions were raised as to its financial connections with politically conservative evangelical groups—connections that suggest a hidden agenda behind its ostensibly non-sectarian mission—and to charges that some of its antiquities were illegally acquired—the latter prompting a special page on the museum’s website.

The history of the Bible collection

But what hasn’t been discussed enough is the extent to which the museum seems to pander to tourism and popular sentiment in its fun-for-the-whole-family, theme-park-like activities scattered through four of the museum’s five exhibit floors.

The rationale behind all this was provided by Hobby Lobby founder Steve Green, the museum’s chairman of the board. At a special media briefing on November 15 he said, “If I put a Bible under glass in a language I can’t even read, it only grabs my attention for so long.” Therefore, because the Bible “has an incredible story to be told,” he felt it necessary to go beyond the rare texts and engage the museum’s audience in a creative way, bringing in “some of the best design firms around the country” to heighten the appeal.

David Trobisch, director of collections, acknowledged to me that the way he and the curators who work under him see it, “it’s an uneasy marriage between a theme park and a museum.” But this is simply how the museum world works today. Other examples he cited were the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, technology museums in general, and the Gutenberg Museum of Printing in Germany, which he described as “interactive from beginning to end.” So here’s what has resulted at the Museum of the Bible.

On the fourth floor, where the centerpiece text collection of over 500 items is attractively displayed, visitors are offered a separate “Drive-Thru History of the Bible” in which a narrator takes us on a wild, wide-screen jeep ride to explore how the Bible came to be written and disseminated throughout the world. A couple of smaller screen extensions of this film appear among the antiquarian text exhibits.

A costumed docent with models of biblical food

But the third floor goes further, eschewing texts and artifacts altogether to treat visitors to “Stories of the Bible.” Three exhibits fill the space: a walk-through multimedia extravaganza dubbed “Journey through the Hebrew Bible;” a noisy and immersive wrap-around cartoon, “Journey through the New Testament;” and “The World of Jesus of Nazareth,” a fabricated first-century village, as cheesy as a roadside Bible land, where costumed docents talk about their ancient lives.

One floor down from there we find the “Washington Revelations” flyboard ride, a sensory-assaulting, vertigo-inducing, high-speed tour of all the major DC public monuments that feature biblical quotes and images. (Being coincidentally a strong activist for church-state separation, I can legitimately say I was sickened by the revelations.)

The first floor of the Museum of the Bible offers the Children’s Experience, which includes Bible storybook arcade games and a Noah’s ark crawl-through maze. But the future holds more. Opening next year in Upper Gallery A will be a “virtual reality experience of biblical proportions,” the content of which is under development.

Running through these entertainments is an approach that struck me as pure Sunday school. All Bible stories are taken at face value, with no interjection of what the historical and archaeological evidence really shows. Trobisch countered that the purpose of the third-floor narratives is to treat the Bible as literature, as a collection of stories.

Artifacts from the Valley of David and Goliath

But the Bible as literature bumps into the Bible as history when we reach the exhibit “In the Valley of David and Goliath,” a collection of archaeological finds from the site of the ancient walled city of Khirbet Qeiyafa in the Elah Valley of Israel. Here, strained efforts are made to connect some of the artifacts to the folktale. For example, excavated sword blades are accompanied by a tenuously related Bible quote and dramatized by a large silhouette of Goliath. Another bit of signage asks metaphorically, “Have the footsteps of King David been discovered in the Elah Valley?” The exhibit’s saving grace is that this is an otherwise serious collection on loan from the Bible Lands Museum in Jerusalem. And consistent with standard practice, items are dated BCE rather than BC as in the rest of the museum.

In addition to there being scant scholarly discussion of the veracity of various Bible stories, there is also little doubt offered, beyond a few bumps in the road, of the Bible’s positive influence on the nation and the world. The trajectory of the Bible’s rise to prominence is onward and upward—a tale of success. Trobisch sympathized with my critique but suggested that the success framework is culturally appropriate for American audiences and thereby makes possible an engaging narrative that will draw people in.

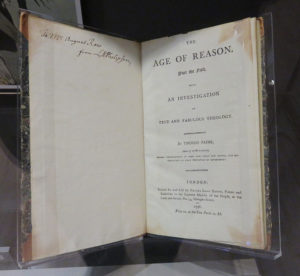

Thomas Paine’s Age of Reason

We see this approach most clearly on the second floor, which is devoted to the “Impact of the Bible” and features a “Bible in America” exhibit. This predominately words-on-walls display is punctuated by a few actual pieces, one of which is a 1796 London edition of Thomas Paine’s Age of Reason, Part the First. But we are told that Paine’s criticism therein of “organized Christianity and its belief in biblical accounts of miracles and the divinity of Jesus… stirred public hostility against Paine, who lost the popularity he had gained with his earlier work, Common Sense.” Nothing is said as to the legitimacy of his arguments or whether the opprobrium was deserved.

As part of a running wall mural, we are told honestly how both sides in the Civil War quoted the Bible for their purposes, particularly on the issue of slavery. While this fact is always useful to note, it’s also too well known to ignore. Thus there’s no big surprise until we come to the inclusion of suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton and her book, The Woman’s Bible, which “questioned key passages that were often used to subjugate women and highlighted other biblical texts to strongly assert the equality of the sexes.” But no mention is made of her atheism or general hostility to the Bible.

Opposite the mural is a special moving silhouette projection of eighteenth-century Protestant evangelist James Whitfield launching what is known as the First Great Awakening. Further down the mural we find Billy Graham and Martin Luther King Jr., creating an overall sense of Christian social progress.

Elsewhere on this floor we learn how great scientists like Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton, as well as specific modern scientists, were positively influenced by the Bible. And we are given narratives of prisoners who have been reformed because they discovered scripture. In a special booth called the Joshua Machine, visitors are invited to sit down and video record their own stories of how the Bible affected their lives.

The Bible’s fashion influence.

The Bible’s influence on culture—from Hollywood movies to women’s fashions to figures of speech—is also highlighted. In this context, pop culture versions of the Bible make up a logical part of the collection, including R. Crumb’s comic book treatment of the Book of Genesis and Brendan Powell Smith’s use of Legos to tell New Testament stories in the Brick Bible. Naturally, one of Elvis Presley’s personal Bibles has been assigned an honored place.

With the museum’s vast size, its promoters boast that it would take nine eight-hour days “to read every placard, see every artifact, and experience every activity.” And the goal is clearly to immerse visitors in the Bible. The museum’s Manna Restaurant serves biblical foods, its rooftop garden grows biblical plants, its elevators feature panoramic and moving video murals of Israel (one on each of the three elevator walls, accompanied by strains of Middle Eastern music), and the grand entrance lobby regales arrivals with a giant 140-foot-long LED ceiling screen depicting cathedral architecture and religious art. Finally, as Disneyland did back in the old days, signposting every “Kodak picture spot” in the park, the printed guide for the Museum of the Bible indicates a prime “selfie spot” for each floor.

So then, when can you go? Not for a week. And all weekend dates are booked solid until the first Sunday in January. The museum is at capacity and online tickets are required. This isn’t the sort of museum you can just show up at the door for.

What does it cost? Well, officially, admission is free. But you have to give your tickets to one of the box office attendants waiting at a long entrance desk. And the LED display over their heads indicates a “suggested donation” of $15 per adult and $10 per child. Moreover, certain “Additional Experiences,” including the Washington Revelations flyboard ride and a couple of guided tours, have a price tag of $8 each. This is, after all, a private museum. Your taxes don’t pay for it.

For my part, I found the Museum of the Bible disappointing. I was hoping for more ancient artifacts, more art, more critical treatment of the material, and less showmanship. Perhaps I’m just old fashioned or too serious. But I did enjoy the display of books by Renaissance humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam, the beautiful illuminated manuscripts from the Middle Ages, and the delightful European paintings depicting themes from the Book of Ecclesiastes. But Washington, DC, offers a trove of collections all over the city, not the least of which are the holdings of the Library of Congress (including a Gutenberg Bible, which is something the Museum of the Bible lacks), the National Gallery of Art, the National Archives, and the various Smithsonians.

So unless the Bible is really your thing, I would give preference to other choices when visiting our nation’s capital.