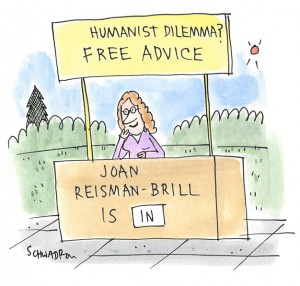

The Humanist Dilemma: When Questioned during Jury Selection, What If You Leave Something Out?

Experiencing an ethical dilemma? Need advice from a humanist perspective?

Send your questions to The Humanist Dilemma at dilemma@thehumanist.com (subject line: Humanist Dilemma).

All inquiries are kept confidential.

Beyond a Reasonable Doubt: I finally got called for jury duty without any more “get out of court free” excuses. I decided it would be better to go ahead and serve on the criminal case I was being screened for and be done for six years, rather than wiggling out of it once again only to be thrown back into the jury pool, possibly within a month.

As it happens, the case looked interesting and mercifully brief, and I found the process really fascinating (I love Law and Order). We saw the accused and were informed that there was no question he stabbed someone in the back of the head. The question, rather, was whether he intended to kill the victim. We were also told that the accused would probably not take the stand; that it wasn’t a domestic violence case but domestic violence would be part of the case; and that we would not be informed of the defendant’s criminal record. We had to swear (or affirm) that none of this information, or lack thereof, would influence our ability to judge the case strictly on the evidence presented. We were told repeatedly that “beyond a reasonable doubt” was much more important than “probably” guilty.

Although jury selection would take three full days, we were assured that it would only take two days to come to a verdict. When it was my turn, even though I affirmed I could follow all the instructions fairly, I couldn’t help but think the accused wasn’t testifying because he would incriminate himself; that it was very likely he was “probably” aiming to murder, for which we’d have to acquit because there wouldn’t be enough hard evidence to prove it beyond a reasonable doubt; that he must have a long rap sheet, including domestic violence; and that the case would be a slam dunk—guilty or innocent—if the judge was so certain we would decide in just two days.

Despite my efforts, including keeping my ambivalence to myself, I was dismissed. The lawyers seemed to reject everyone who expressed any deep-down reservations about the accused not testifying, not being able to know his history, agreeing to rule not guilty if he seemed “only” probably guilty. I really can’t imagine that everyone didn’t harbor those same thoughts, and that many cases find people guilty even when the evidence isn’t airtight, such as unless all the witnesses testified he was screaming, “I intend to murder this guy!” while he was wielding the knife.

Was I committing perjury by not admitting my conflict? Don’t most jurists?

—Only Partially Impartial

Dear Impartial,

Who can forget the O.J. Simpson homicide trial, in which the jury was compelled to acquit because the glove didn’t fit? Although some believe police tampered with the evidence, others believe his extraordinary, high-powered defense team pulled off a coup, brilliantly playing our justice system to let a double murderer go free.

In order to function, our legal system requires conforming to generally accepted rules and definitions that are serviceable but imperfect. Beginning with the presumption of innocence, it is skewed so that more guilty people will be exonerated than innocent people will be convicted—and to my mind, that’s better than the reverse. We can’t each be making judgments based on what we personally think is fair at this moment or in this situation—we need to comply with the standards that have been developed and adhered to over time, even if they may seem wrong-headed. There are instances when “beyond a reasonable doubt” is an unreasonable standard, when circumstances point to a guilty verdict but don’t meet the criteria established by the court. And of course, no lawyers or judges can peer into jurists’ minds and see what’s really going on in there, despite what those jurists may say or not say.

Although our system is deeply flawed, it may be the best there is. And regardless of how good or bad it is, it’s what we’ve got, so we’ve got to work with it. I encourage everyone to accept, and even embrace, their duty to serve—whether it means spending a couple of days every few years only to be sent away without sitting on a case, or spend a week or more sitting on a case that isn’t nearly as entertaining as a TV drama. I also encourage everyone to vote. These things can have a positive impact, even if it’s often hard to tell.

As to whether you were committing perjury, I suppose technically you were. But you shouldn’t feel too guilty about it. You did what you did, behaving as a normal citizen, and the system did what it did, weeding you out as surely as if you’d admitted you might not be fair under the court’s definition of fairness. Fair enough.

For a hilarious mash-up of Law & Order and a beloved fairy tale (oh my, I never thought about it like that), check out this video: