The Best of The Humanist: Humanist Philosophy 1928-1973

BY CHARLES MURN

HUMANIST PRESS, 2018

450 PP.; $25.00

Charles Murn’s new collection, The Best of The Humanist: Humanist Philosophy 1928-1973, is a great resource for all humanists. Many of us cherish George Santayana’s 1918 quote, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” but few of us started our lives as humanists, so the “past” is an adopted one. The better we come to know this humanist past, the more we will appreciate it—and be able to broaden and deepen its present.

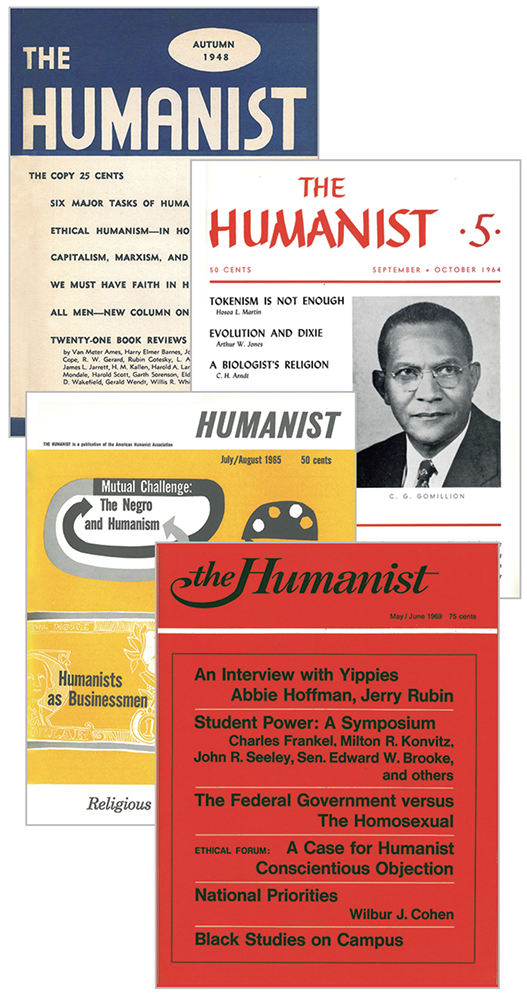

Murn explores the early period of our movement—from before Humanist Manifesto I to Humanist Manifesto II. The larger American context included the Great Depression, the New Deal, World War II, and the Cold War. During these years, humans were wrestling with communism, fascism, socialism, and capitalism. These ideologies, and their complex relationships with the Western religious heritage, made the humanist alternative essential.

Having carefully read the many articles published in the New Humanist and the Humanist (its successor) during that forty-five-year period, Murn organizes the ideas into eleven chapters and many subsections, each having selected themes and persons. His own comments precede the fully reproduced articles.

Western skepticism, from the early Greeks to our time, has doubted the reality of dualistic realms and supernatural persons. But then what? Human history has been plagued by battles between different beliefs and contentions between different values. Not until the seventeenth century did modern science begin to give us more accurate pictures of our physical world. The fruits of this movement were many, as we began to imagine and achieve progress. Today we live longer lives; we suffer less from diseases; families are smaller; and fewer children die young. Myths about our so-called racial and gender differences have weakened (promoting universal education), and fewer of us live in poverty or die in battles.

Since Charles Darwin published his theory of evolution, we have learned that the cosmos and our tiny corner of it are indifferent to various living things that evolve. Add to this our growing doubts about afterlives and reincarnations. Humanism emerged with its selection and creation of values based on science, reason, evidence, and compassion. In many ways it was a possible new religion fostering human fulfillment and happiness in the here and now.

Chapters of the book explore many aspects of humanism: philosophy; types; sources; scientific method; the unknown; nontheist religion; emotion and spirituality; morals and ethics (Murn distinguishes these terms as personal and social, respectively); psychology; the arts; other life forms. The articles included are by scientists, philosophers, psychologists, philanthropists, activists, authors, academics, and at least one famous architect. Many of yesterday’s humanist writers will be familiar to contemporary humanists, and all still have vital things to tell us.

Chapters of the book explore many aspects of humanism: philosophy; types; sources; scientific method; the unknown; nontheist religion; emotion and spirituality; morals and ethics (Murn distinguishes these terms as personal and social, respectively); psychology; the arts; other life forms. The articles included are by scientists, philosophers, psychologists, philanthropists, activists, authors, academics, and at least one famous architect. Many of yesterday’s humanist writers will be familiar to contemporary humanists, and all still have vital things to tell us.

Humanism remains a rare identity in the United States—and a tiny movement in the larger world. Murn’s introductions and wide selection of articles will be useful to humanists’ understanding of their current movements and will help interested readers in discovering the roots of modern humanism. Politically, emerging democracy is the context, and philosophically, John Dewey’s pragmatism/instrumentalism is the basis of modern humanism. Both are recent in our human history and closely linked with the development of science and industrialism.

Some critics of humanism have used the “scientism” pejorative to criticize a position that presumably takes all of its values and wisdom from science. Reading this volume renders that critique irrelevant. While many new values have emerged in recent centuries, science does not select among competing values. Murn furthers this argument by describing ways that humanists involve the arts and humanities, noting the particular role that some science-fiction literature has played in stimulating the imaginations of humanists.

The many values pioneered by our movement in the period the book covers are impressive. We had fresh things to say about racism and sexism. We also had sensitivity to the importance of science and the possible misuses of science, and particularly the technologies that it developed. We were sensitive to the role of emotion in human life along with reason. Our concerns were not only for other humans, but for all of life and the global environment. We saw clearly the dependence of democracy upon lifelong secular education. We saw the harm done by traditional views of sexuality and sexual orientations. We reached out critically to all human cultures, searching for ways to help them move into scientific modernity.

Murn correctly reminds us that technologies emerging from science, as well as areas of research, are not so much selected by scientists themselves as they are by corporate-government forces. This explains what he notes as “the slow progress that humanism has made in reducing destructive use of scientific knowledge.” May our knowledge- and value-based activism modify this!