Celebrating 200 Years of Walt Whitman

“And I say to any man or woman, Let your soul stand cool and composed before a million universes.

And I say to mankind, Be not curious about God,

For I who am curious about each am not curious about God,

(No array of terms can say how much I am at peace about God and about death.)

I hear and behold God in every object, yet understand God not in the least,

Nor do I understand who there can be more wonderful than myself.”

IN 1844, AT AGE TWENTY-FIVE, Walt Whitman read an article by perhaps the preeminent poet, essayist, and intellectual of his day, Ralph Waldo Emerson. In it Emerson made the case that America needed a fresh new voice in poetry to be able to properly reflect a rapidly emerging society. Whitman decided that he should be that voice.

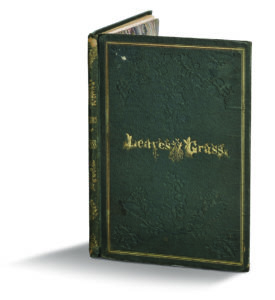

He was a journalist and itinerant schoolteacher in various places on New York’s Long Island where he was born on May 31, 1819, eventually settling in the city of Brooklyn. In those days, New York City was entirely the island of Manhattan, separated from Brooklyn by the East River. Brooklyn was nothing less than a bustling, burgeoning urban environment, thick with the matters of commerce that proved a more than adequate source of ideas and inspiration for the young poet. For ten years Whitman struggled to produce but a dozen lengthy poems, found himself a print shop, and in 1855 created a volume doing very nearly all the work himself. It was titled Leaves of Grass.

Nothing like it had even been written prior and the book was initially presented as a collection of oddities. Poetry in those days still assumed the upper floor in the ivory tower of literature, and Whitman effectively took it out into the street. The print run of the first edition of Leaves of Grass was 795 copies, sized so that the collection could easily be carried in the pocket of the reader. Using his great literary flair, Whitman also wrote several shining reviews of his own book. He also did the obvious thing and sent a copy to Emerson up in Concord, Massachusetts. Emerson’s reply was nothing less than laudatory, praising Whitman thusly:

I am not blind to the worth of the wonderful gift of Leaves of Grass. I find it the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed.

I greet you at the beginning of a great career, which yet must have had a long foreground somewhere, for such a start. I rubbed my eyes a little, to see if this sunbeam were no illusion; but the solid sense of the book is a sober certainty. It has the best merits, namely, of fortifying and encouraging.

For most poets, these are dreams that never come true; that one should, at the get-go, receive the highest praise from the very highest authority. Whitman put out a second edition in 1856 that included the letter in its entirety, with a small excerpt on the volume’s cover. Emerson had, in fact, visited Whitman in Brooklyn, and Whitman never reported his intentions about the second edition. When it came out Emerson was apparently furious, but Whitman carried on and never looked back.

For most poets, these are dreams that never come true; that one should, at the get-go, receive the highest praise from the very highest authority. Whitman put out a second edition in 1856 that included the letter in its entirety, with a small excerpt on the volume’s cover. Emerson had, in fact, visited Whitman in Brooklyn, and Whitman never reported his intentions about the second edition. When it came out Emerson was apparently furious, but Whitman carried on and never looked back.

Curiously, Whitman became perhaps the most severe critic of his seminal collection. Up until the time of his death in 1892, he produced six different editions, adding to and editing the original Leaves of Grass. It’s certain he felt he had improved upon it, but whether that was the case depends very much on whom you ask. In some respects, a diamond can be cut but once. He felt strongly about perfecting the work he produced, and yet he was certain these were poems for the ages.

But Whitman’s beginning had been as a printer and a journalist in New York at a time when newspapers were the sole means for the conveyance of news and information, their numbers plentiful, and the competition among them fierce. The publication that offered the most literary flourish succeeded, and Whitman became a very capable writer.

During the bleak days of the Civil War, Whitman moved to Washington, DC, working at several government agencies. He made it his business to visit the hospitals that were full to overflowing with the suffering battle casualties from the Union side, one of whom was his brother, George. He sat with the wounded to share their stories and their troubles, and took dictation of letters they hoped to send home to loved ones. The horrors Whitman witnessed and heard about from these young soldiers must have exacted a heavy toll on him. He also adored Abraham Lincoln and would watch for the very frequent passing of the president’s carriage on its way to the White House from the Old Soldiers Home three miles away, where Lincoln kept a cottage to allow some refuge from the unbearable DC summers. His homage to Lincoln, When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d remains one of the great American poems.

Whitman’s arrival on the scene of American letters, poetry in particular, came at a time when poetry as an art form was very staid and formal in both subject matter and form. It had existed for a privileged few poets and readers of poetry who had access to its much-vaunted ivory tower. Emerson, the famous Transcendentalist and initial Whitman celebrator, was surely part of that literary elite who were dedicated to the preservation of a certain status quo. What Walt Whitman did with Leaves of Grass could be seen as a challenge to that privileged ideal. I suggest he did more than that—he demolished it.

He was part of a revolution of change in America: social, technological, and physical change on the heels of an enormous influx of new Americans from all over the globe who brought with them their ideas, their ethics, their sounds, and their scents as well. Whitman, living largely in Brooklyn, was at the center of the action and he immersed himself in it in ways that overwhelmed his senses. His response was to capture it all in poems, the likes of which had never been read before, works that celebrated not only himself as a free spirit but the roiling life around him, and especially the rhythms of the great city that was expanding in every imaginable way. I would say, without hesitation, that if one were to try and understand the America of the mid-nineteenth century, the richest course would mine the words of Walt Whitman.

His poems were long rambling songs of the exuberance he felt at being alive and at feeling himself in a moment of an exploding destiny. They were sensitive and sensory, sensual in ways that had never been seen on a page, and they broke every rule in existence at the time about the nature of literary expression. Leaves of Grass not only lost Whitman his job after it was read by his boss, Secretary of the Interior James Harlan, it was savaged by critics (one of whom suggested that the only appropriate thing for Whitman to do at that point was commit suicide). Critic Rufus Wilmot Griswold called Leaves of Grass “a mass of stupid filth” and characterized its author as a “filthy free lover,” guilty of “that horrible sin not to be mentioned among Christians.” Many other prominent people went so far as to pronounce the poems obscene.

It is generally believed that Whitman was a homosexual, something that might have influenced his words and subject matter, and scholars have often referred to him as humanistic, perhaps an outgrowth of his Quaker parents. So much of his verse struck the familiar chords of democracy, justice, personal freedom, and acceptance of the differences among people, a reverence for and celebration of nature, and a lavish praise of the human species. He seemed to be a spiritual being, entirely grounded in the riches he found in his own life and immersed in its many wonders and mysteries. Whitman never referred to himself as a humanist but the expression of principle and his bold assertions about the matters of living seem to manifest a familiar resonance.

But here is what really matters most about Whitman the poet (also considered the father of free verse): the incalculable number of artistic endeavors since Whitman that have surely drawn both inspiration and courage from him. Not only poets but musicians, novelists, playwrights, photographers, painters, and even philosophers owe some debt to this man, and not only Americans either. I am a poet and venture there hasn’t been an American poet since Whitman who, when asked who it was that influenced them to write, wouldn’t say his name first, with both gratitude and reverence.

Sadly, Whitman suffered a paralytic stroke in 1873 that left him dependent on his brother George and then a friend named Mary Oakes Davis, who moved into a small house with Whitman in Camden, New Jersey, to be his caretaker in exchange for room and board. The Good Gray Poet (as he had been dubbed) died some twenty years after that stroke in March of 1892. His death brought some one thousand people to pay their respects. The eulogy was delivered by none other than the Great Agnostic himself, Robert Ingersoll, who said, among his many praises of Whitman:

[H]e accepted and absorbed all theories, all creeds, all religions, and believed in none.

He was the poet of the natural, and taught men not to be ashamed of that which is natural. He was not only the poet of democracy, not only the poet of the great Republic, but he was the Poet of the human race. He was not confined to the limits of this country, but his sympathy went out over the seas to all the nations of the earth.

Whitman was a man of great belief in the art that he made. It makes me smile to think how pleased he would be to know of the standing he enjoys not only in the US but around the world, two hundred years after his birth. As a humanist, as a human, do yourself a favor and spend some time with Walt Whitman’s poems.

From Leaves of Grass

Song of Myself, Section 48

I have said that the soul is not more than the body,

And I have said that the body is not more than the soul,

And nothing, not God, is greater to one than one’s self is,

And whoever walks a furlong without sympathy walks to his own funeral drest in his shroud,

And I or you pocketless of a dime may purchase the pick of the earth,

And to glance with an eye or show a bean in its pod confounds the learning of all times,

And there is no trade or employment but the young man following it may become a hero,

And there is no object so soft but it makes a hub for the wheel’d universe,

And I say to any man or woman, Let your soul stand cool and composed before a million universes.

And I say to mankind, Be not curious about God,

For I who am curious about each am not curious about God,

(No array of terms can say how much I am at peace about God and about death.)

I hear and behold God in every object, yet understand God not in the least,

Nor do I understand who there can be more wonderful than myself.

Why should I wish to see God better than this day?

I see something of God each hour of the twenty-four, and each moment then,

In the faces of men and women I see God, and in my own face in the glass,

I find letters from God dropt in the street, and every one is sign’d by God’s name,

And I leave them where they are, for I know that wheresoe’er I go,

Others will punctually come for ever and ever.

So Long! (excerpt)

Camerado, this is no book,

Who touches this touches a man,

(Is it night? are we here together alone?)

It is I you hold and who holds you,

I spring from the pages into your arms—decease calls me forth.

O how your fingers drowse me,

Your breath falls around me like dew, your pulse lulls the tympans of my ears,

I feel immerged from head to foot;

Delicious, enough.

Enough O deed impromptu and secret,

Enough O gliding present—enough, O summ’d-up past.

Dear friend whoever you are take this kiss,

I give it especially to you, do not forget me,

I feel like one who has done work for the day to retire awhile,

I receive now again of my many translations, from my avataras ascending, while others doubtless await me,

An unknown sphere more real than I dream’d, more direct, darts awakening rays about me, So long!

Remember my words, I may again return,

I love you, I depart from materials,

I am as one disembodied, triumphant, dead.

Continuities

(From a talk I had lately with a German spiritualist.)

Nothing is ever really lost, or can be lost,

No birth, identity, form—no object of the world.

Nor life, nor force, nor any visible thing;

Appearance must not foil, nor shifted sphere confuse thy brain.

Ample are time and space—ample the fields of Nature.

The body, sluggish, aged, cold—the embers left from earlier fires,

The light in the eye grown dim, shall duly flame again;

The sun now low in the west rises for mornings and for noons continual;

To frozen clods ever the spring’s invisible law returns,

With grass and flowers and summer fruits and corn.

Song of Myself (Verse 52)

The spotted hawk swoops by and accuses me, he complains of my gab and my loitering.

I too am not a bit tamed, I too am untranslatable,I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world.

The last scud of day holds back for me,

It flings my likeness after the rest and true as any on the shadow’d wilds,

It coaxes me to the vapor and the dusk.

I depart as air, I shake my white locks at the runaway sun,

I effuse my flesh in eddies, and drift it in lacy jags.

I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love,

If you want me again look for me under your boot-soles.

You will hardly know who I am or what I mean,

But I shall be good health to you nevertheless,

And filter and fibre your blood.

Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged,

Missing me one place search another,

I stop somewhere waiting for you.