Imperial Borders and Mythical Frontiers The Cruel Truth of Immigration and American Empire

IMMIGRATION IS THE FOCAL POINT of the political moment, and it is the thing we Americans think about most foolishly—with the least history or context, with little common sense, and almost no perspective. It’s talked about as a new and unique national crisis for the very same reasons it’s been talked about as a new and unique crisis throughout our history; everything said about Hispanic and Middle Eastern immigrants today was said about Irish and Jewish immigrants before. We treat immigration as if it were a morality tale of human rights and fundamental to the very meaning of our national identity, when really it is a story about imperial exploitation and the separation of people by economic hierarchies rather than by national borders.

The world has open borders for the rich and closed borders for the poor. So Coca-Cola’s board of directors is as diverse as a community college commercial, and border patrol doesn’t ask for its papers when the company comes to Mexico to bottle up a town’s water supply. But the Salvadoran fleeing village violence has to wait in Mexico for years before a judge decides whether she merits entry as a refugee.

If today’s mass immigration is going to end in anything but catastrophe, it’s going to require facing unpleasant truths about American empire and global capitalism. It’s much easier to panic about the Hispanic roofer who just moved to town than to confront those who control the economic and political forces that pushed him there. But that’s exactly what we must do. We can weep and woe about either the plight or burden of immigrants, but if we don’t address why they’re migrating then we’re just going to see, as Barack Obama’s Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano put it, fifty-one-foot ladders for every fifty-foot wall.

And it isn’t enough to just say all are welcome. Of course all should be welcome—but only those who want to come. We can’t accept being the refuge from the problem if we’re also the source of it.

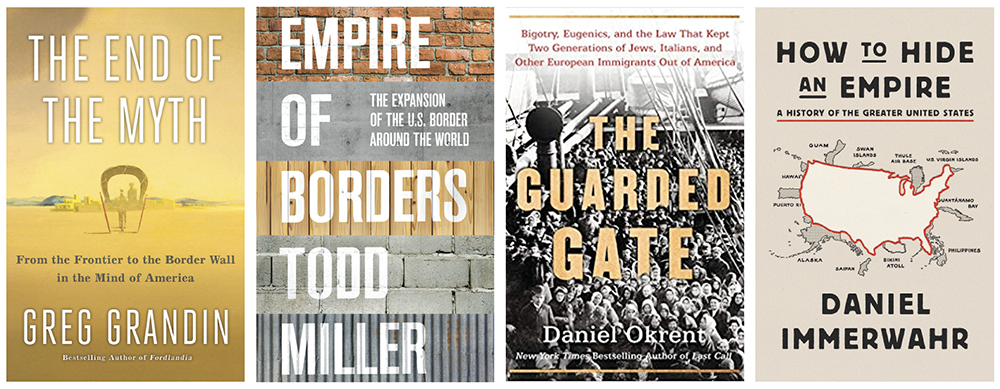

I once heard that to get what you want, you first have to admit who you are. Thankfully, a string of books published this year shows us just that when it comes to our foreign and immigration policies—Daniel Immerwahr’s How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States; Daniel Okrent’s The Guarded Gate: Bigotry, Eugenics and the Law That Kept Two Generations of Jews, Italians, and Other European Immigrants Out of America; Greg Grandin’s The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America; and Todd Miller’s Empire of Borders: The Expansion of the U.S. Border Around the World. (I’ll mostly be analyzing the latter two, although all four are worth reading.)

The End of the Frontier Myth

Grandin’s The End of the Myth is about the collision between a lie we tell ourselves about the past (that the expansion of our westward frontier was a noble conquest of open land and empty space) and a lie we tell ourselves about the present (that mass immigration across our southern border has reached such a level as to be a national crisis). The myth of the gentle, self-sufficient settler caravan of the nineteenth century is crossing paths with the myth of the sinister, resource-stealing migrant caravan of today. The border wall, writes Grandin, is “America’s new myth, a monument to the final closing of the frontier.” He provides a history and analysis of these two myths—where they come from, who they appeal to, where they correspond with reality and where they don’t, as well as the evil things they each hide with varying degrees of paranoia and sentimentality.

The frontier became a myth as soon as it ceased being a reality. The 1890 US census proclaimed that there was no more open land in the United States—the native inhabitants having been killed, pushed, or scattered and Mexico subdued below the Rio Grande River. Three years later, in 1893, Frederick Jackson Turner presented to an underwhelmed audience at the World’s Fair in Chicago his now famous “Frontier Thesis.” He proposed that in our country’s history thus far, the frontier had served as a “safety valve” for labor agitation and political extremism. Those who couldn’t find work in the industrial and urban eastern part of the country could always migrate west, therefore wages remained relatively high and the steady influx of European migrants relatively welcome.

During his 1858 US Senate campaign, Abraham Lincoln had said that the frontier was an “outlet for free white people everywhere, the world over—in which Hans, and Baptiste, and Patrick, and all other men from all the world, may find new homes and better their condition in life.” As Turner saw it some three decades later:

The free lands are gone, the continent is crossed, and all this push and energy is turning into channels of agitation…a people composed of heterogeneous materials, with diverse and conflicting ideals and social interests…is now thrown back upon itself…and the nation seems like a witches’ kettle.

Of course, the frontier was never, as Turned called it, “free land.” There were Mexicans and American Indians who, although lacking legal documents, fought for land they believed was their own because, after all, they were using it. Nor was westward expansion the result of individual initiative and can-do spirit, as it’s commonly imagined, but rather of government policy. As Grandin lays out, it was the federal government that negotiated rights to everything east of the Mississippi River, asserted the right to all tribunes of the river its surveyors could find, bought millions of miles of heartland from France, and then paved roads, irrigated land, and built military outposts.

Nor was the frontier a realistic alternative to social-democratic agitation. In fact, it was more of a get-rich-quick scheme that served a dual purpose for the ruling class. First, it built fortunes for extractors who took what they could from the land (copper, timber, fish, etc.) and sold it to starry-eyed workers who bought it with borrowed money (making fortunes for creditors as well). Second, it deflected workers from, in Grandin’s words, “waging class war upward—on aristocrats and owners” to “wag[ing] race war outward, on the frontier,” on behalf of those aristocrats and owners.

The stoppage of westward expansion didn’t last long after the 1890 census. The Pacific Ocean was where the Continental United States ended but not the US government’s imperial ambitions. “There is the United States on the map whose ‘sea to shining sea’ shape everyone knows,” writes Miller in Empire of Borders, “and there are the borders of the United States empire, which makes a completely different shape, invisibly extending farther than once seemed possible.” The shape of the American empire’s borders transgressed those of the American nation’s in 1898 when the US took the Philippines from Spain and turned Cuba into a “protectorate.” Then came invasions of Nicaragua, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic. As Woodrow Wilson wrote in 1902, “We made new frontiers for ourselves beyond the sea.”

“Border Fascism”

As the American empire spread, the American nation fortified its borders. At the turn of the century the first checkpoints were built along the US-Mexico border. In 1917 laws were passed that mandated literacy tests, entry fees, and quota restrictions for immigrants, and in 1924 the US Border Patrol was created. In the 1920s, Herbert Hoover deported over a million people to Mexico (an estimated 60 percent were US citizens of Mexican descent), and in his 1932 presidential campaign he scapegoated Mexican migrant workers for low wages and lack of jobs at home. The “border-fication of our politics” (as Grandin calls it) had begun. As we invaded more countries, we worried that we were under threat of secret invasion ourselves. Anti-immigrationists in the 1920s fabricated stories of thousands of Communists sneaking in through our southern border (years later it was rumored the whole Chinese Army was in Mexico prepping for invasion). Today, anti-immigrationists claim Arabic pamphlets are found in the Arizona desert, left by Islamic terrorists coming in the same way the make-believe Communists did.

“For most of the twentieth century,” writes Grandin, “the United States’ border with Mexico had served as the shadow side of the nation’s frontier universalism, a two-thousand-mile-long margin to which racist extremism was relegated.” The extremism Grandin catalogs—the violence and exploitation—is horrifying. Hispanic migrant workers murdered by anti-immigrant goons; migrant workers transported to Texas farms by US Border Patrol only to be raided and deported by that same agency just before payday; Hispanic women traded to judges for a blind eye and to a sports team for season tickets.

“It is tempting,” writes Grandin, to think the border myth is a “more accurate assessment of how the world works, especially when compared to the myth of the frontier.” The border wall, he continues,

is a monument to disenchantment, to a kind of brutal geopolitical realism: racism was never transcended; there’s not enough to go around; the global economy will have winners and losers; not all can sit at the table; and government policies should be organized around accepting these truths.

Grandin is right in his implication. Humans can’t live on facts alone. We need myths, but they should be ones that don’t falsify the past or obscure the present, and the border myth does both. In fact, it gets almost everything wrong: it isn’t an immigrant who takes your job, it’s your boss (“How can someone steal someone else’s job,” a migrant worker subversively asks in Sunjeev Sahota’s novel Year of the Runaway. “Isn’t that up to the boss?”); migrants and refugees aren’t invading us, they’re mostly fleeing from our invasions and our empire (Southeast Asians in the 1950s and ’60s, Central Americans in the ’70s and ’80s, Middle Easterners throughout the 2000s); and, most importantly, building walls won’t stop anyone from trying to come here. What will is helping people build up their own countries, so they don’t feel like their only chance at a decent life is thousands of miles away. That isn’t what we do though. Instead we spend billions of dollars trapping people in poverty and hardship.

People should be free to move and live where they want, but they shouldn’t be forced to move because a corporation poisoned their water supply or a foreign government fomented a military coup or a foreign army destroyed most of their town.

Miller’s Empire of Borders is eye-opening to just how much money, people, and resources we waste on fortifying borders all across the world. “Close your eyes and point to a landmass on a world map,” Miller writes, “and you will probably find a country that is building up its borders in some way with Washington’s assistance.”

Miller travels the world to see a lot of this border-building first hand. He talks with a former BORTAC official (BORTAC being the “special forces” of the US Border Patrol) who administered retinal scans on sheepherders at the Iran-Iraq border. He finds Border Patrol, the US Coast Guard, and the Department of Homeland Security aiding and assisting border security in Puerto Rico to apprehend Dominican Republic “boat people.” (The Dominican Republic is one of the most exploited countries in the Caribbean, if not on earth. The country is fifty percent unemployed or underemployed, its energy, manufacturing, and tourism sectors are almost entirely foreign-owned, and its “free trade zones” immunize these foreign-owned companies from paying local taxes.)

Miller also goes to Manila Bay where the Philippine’s coast guard is headquartered in a watchtower built by Raytheon and financed by the US Department of Defense. Next he’s on a bus that’s stopped by Mexico’s border police hundreds of miles inland from the country’s border with Guatemala—again thanks to our federal government, which in 2014 gave Mexico billions of dollars to launch its “multi-layered” border security. Since the launch Mexico now annually deports more Central Americans than the United States. And those Central American governments are getting their piece of the US-border-security pie too. Since 2008 the US program Central American Regional Security Initiative (CARSI) has given nearly $1 billion to Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador for border security. Over that same time the Pentagon sent those governments $357.2 million to expand, upgrade, and militarize their border security.

America the Planetary

The justification for all this labor and spending has varied over time and depends on the audience. After 9/11 the Washington, DC, establishment’s security consensus was that the only effective way to protect Americans from terrorism was to fight terrorism wherever it was. And since terrorism was everywhere, so should be the American security apparatus. As the 9/11 Commission Report put it, the response to an attack on an American anywhere in the world should be handled with the same decisiveness and severity as if it happened in the United States. “In this sense,” the commission concluded, “The American homeland is the planet.” This justified both the physical and cyber expansion of our security apparatus. It became imperative that we track the comings and goings of “persons of interest” around the world with the same omnipotence and precision as if they were moving between Iowa and Utah. We already had a global security apparatus before our “war on terrorism,” but 9/11 inflated and intensified it. And after the anti-terrorism hysteria fizzled out, there were always other justifications. The pre-war global security apparatus was largely built on the pretext of anti-Communism and our “war on drugs,” and so they were brought back into the fold, and the three were even linked. In the 2000s State Department officials started giving lectures on the dangerous axis of Islamic terrorists, Central American drug runners, and Bolivian governments that dared use oil money for anything but dividend checks.

Almost concurrently with our “war on terrorism” it was also decreed that our national borders were actually the last line of our national sovereignty rather than the line of national sovereignty. Border security, it was declared, started in Jordan and Guatemala rather than Texas and Arizona. As General John Kelly, Donald Trump’s former chief of staff and before that head of the US military’s Southern Command, told reporters during a January 2017 White House briefing: “Border security cannot be attempted as an endless series of ‘goal line stands’ on the one-foot line at the ports of entry or along the thousands of miles of border between this country and Mexico…the defense of the Southwest border starts 1,500 miles to the South, with Peru.” And if the government of Peru doesn’t want to serve on the front line of our border security? Well, you don’t spend a trillion dollars a year on military and espionage for nothing.

The History of Anti-Immigration Scaremongering

Despite the moral homilies of some well-meaning politicians, the United States has always had an anti-immigration streak to it. The Statue of Liberty might read, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” but over a hundred years before she was built, people like John Adams were already complaining about German immigrants for refusing to learn English or assimilate to WASP-ish manners. And if you asked the man on the street in the 1850s what the crisis of his time was, more than likely he’d tell you Irish-Catholic immigration than slavery. Irish (and other European) immigrants were escaping famines, but anti-immigrant organizations and political parties were formed with the assumption that they were pawns in a plot either of the Democratic Party trying to steal elections, European monarchs trying to empty their poor houses, or the Vatican trying to convert Protestant America to Catholicism. “Jesuits are prowling all parts of the United States in every possible disguise to disseminate Popery,” reported a Protestant newsletter in 1834. And this wasn’t just crank-fringe opinion. The Massachusetts Sanitary Commission warned in 1850 that “Pauperism, crime, disease, and death stare us in the face” if the state continued admitting immigrants. Irish immigrants were accused of disloyalty because of their Catholicism (“The man who is a Roman cannot be an American,” a Milwaukee newspaper editorialized in 1856); Catholic priests were accused of being sexual sadists and perverts (“nunnery confessions,” erroneous stories about women surviving torture and debauchery in nunneries, were among best-sellers in the nineteenth century); and, in a quote that reveals the complete incoherence and political opportunism of notions like “Western Civilization,” the Catholic Church was charged with being a foreign religion of “the East” that Rome was trying to impose on the United States.

Our empire and border-security state are a feedback loop, and both serve an international economic hierarchy rather than protect our country.

Of course, not all the negative associations were statistically wrong: Irish immigrants did overwhelmingly vote Democrat, and they did live as the urban underclass of most cities (US cities such as St. Louis, Boston, and Cleveland were majority immigrant), with all the attended vices that brings with it. But these vices had nothing to do with their national characteristics and everything to do with their servile relationship to mainstream American society.

America’s immigration history is usually broken down into three waves of mass immigration: the 1840s to 1860s, the 1890s to WWI, and 1965 until today. The fears, arguments, and grievances of anti-immigrationists during all three waves have been largely identical. Names change—now Islam instead of Catholicism is the Eastern religion that threatens our way of life—but the culture of fear does not.

One thing that does fluctuate in the anti-immigration attitude is the emphasis on immigrants as either deadbeats living off government handouts or job-stealers undermining the price of labor. In the first wave of mass immigration (1840s to 1860s), the frontier was not yet closed and the economy was doing relatively well, so anti-immigrationists mostly emphasized crime, poverty, and papal conspiracy. The Irish, it was said, were leaving the beaten-down potato fields of Munster and going straight into the poor houses of Boston. With the second wave of mass immigration (1890s to WWI), the frontier was closed and the economy went through multiple depressions, so anti-immigrationists emphasized the impact of immigration on native workers. Mass immigration was seen as benefitting employers by lowering the cost of labor (either because immigrant workers were willing to work for less than native workers or because a larger supply of workers than demand for work necessarily lowered labor costs) and it benefitted middle-class professionals because lower labor costs meant lower consumer prices for middle-class luxuries.

The latter is the anti-immigration perspective of Edward A. Ross’s 1914 The Old World and the New: The Significance of Past and Present Immigration to the American People, much of which could’ve been written today (again, just with name changes). Ross likened cheap immigrant labor to slavery and said that America’s ruling class was culturally and ethnically changing the country just to make a quick buck. In Ross’s case, he had in mind Jews, Italians, and Slavs (who, oddly enough, he didn’t consider “white”), while today’s anti-immigrationists have in mind Hispanics, Arabs, and Africans. Whole industries, Ross lamented, had been “foreignized”—garment manufacturing by Jews, construction by Italians, and coal by Slavs—and when Ross objected to industrialists about this hiring practice he was told, “Americans nowadays aren’t any good for hard or dirty work.” Just as today we’re told immigrants are “doing the work Americans won’t”—which is true: immigrants around the world, in practically every country, do the work nobody will do unless they’re absolutely desperate.

Ross was also obsessed with the declining US birthrate (reading anti-immigrationists throughout American history, our native birth rates seem to have somehow always been in decline), and he predicted that “in a generation, complaint will be heard that the Slavs, too, are shirking big families, and that we must admit Persians, Uzbegs, and Bokhariots in order to offset the fatal sterility that attacks every race after it has become Americanized.”

The labor issue of immigration was almost always intertwined with the eugenic. As the eugenicist Madison Grant wrote in his doom-ridden 1922 book The Passing of the Great Race, “The American sold his birthright in a continent to solve a labor problem.” The second wave of mass immigration coincided with the intellectual fad of race science, where people were categorized into a hierarchy of races. Elite opinion was paranoid that immigrants from central and eastern Europe were “poisoning” or “polluting” the “racial stock” of the country. Hundreds of books, articles, and speeches poured forth trying to prove that people were divided into races and that one’s race determined one’s character and social value. Racial categories, and the position of races in the hierarchy, varied from racist to racist. Sometimes race was just based on nationality; other times it was based on geography, language, head shape, or ancient-mythical tribe affiliation. The purpose of all this was to prove that new immigrants were naturally stupid, lazy, and cowardly, and that they were doomed to permanent domination by the superior races that were already here (including previous immigrants such as those with German ancestry).

When new immigrants found success, despite their supposed innate limitations, the racial categories were simply revised. It was decided, for example, that the “Italian race” was actually two races: northern “Teutonic” Italians (who were good) and southern dark-skinned Italians (who were bad). As Okrent shows in Guarded Gate, this whole racial way of thinking was intellectually pathetic and morally disastrous, the logical conclusion of which was eugenics in the United States and Nazism in Germany.

Breaking the Cycle

Our anti-immigration cycle seems fated to repeat itself, at least so long as we keep repeating our responses. When Bill Clinton was told NAFTA would cause mass immigration from Mexico, as thousands of Mexican farms would be unable to compete with federally subsidized US agricultural imports, his response was not to negotiate into the trade agreement bilateral compensation plans and labor laws but to increase Border Patrol’s budget and staff. For the ruling classes in Mexico and the United States, NAFTA and a beefed-up border security meant low regulatory costs and factory wages on the Mexican side and easy-to-control migrant workers and easy-to-manipulate native workers on the US side.

So long as we treat immigration as a security matter, without resolving its political and economic causes, nothing will change. So long as decision-making is concentrated at the top—where pickers in the fields have no say in what gets done with their produce and factories can be moved across the world without input from those doing the work—we will have xenophobia and nativism. So long as the world is divided between the haves and have-nots, we will see mass immigration. People should be free to move and live where they want, but they shouldn’t be forced to move because a corporation poisoned their water supply or a foreign government fomented a military coup or a foreign army destroyed most of their town. Immigration policy is really foreign policy and foreign policy is really domestic policy. Freedom and democracy here is the only way to spread freedom and democracy elsewhere. But this is also true with hierarchy and oppression. Our empire and border-security state are a feedback loop, and both serve an international economic hierarchy rather than protect our country.

The obvious solution to mass immigration is to raise the standard of living in the source countries. To encourage democracy in those places rather than plutocracy. To train farmers and doctors rather than border guards and military officials. To build roads and hospitals rather than army bases. To teach methods of water preservation rather than poison water resources while extracting minerals. To protect order rather than spread corruption and chaos. In other words, to be international rather than imperial. But our ruling class does the opposite of the obvious and then we demonize the people who flee from the consequences. Stopping our anti-immigration cycle will require us to break the economic wheel that spins it.