If English Was Good Enough for Jesus…

Listening to talk radio is like picking a scab. It’s hard to stop. And why stop? Despite its reputation for offering little more than anonymous plebeian banter, there is often some wisdom to be gleaned from hosts and callers alike. There are thoughtful, intelligent people saying thoughtful, intelligent things. There are also plenty of morons saying thoughtless, unintelligent things.

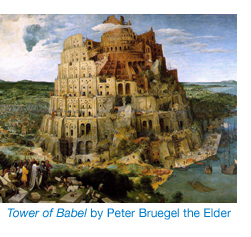

In the latter category, the latest phrase to permeate talk radio is “Tower of Babel.” For Michael Savage and Sean Hannity callers, bilingual signage, schools, and 1040 forms mark the beginning of our next cataclysmic fall. These concerned citizens seem to believe that just as homosexual marriage threatens heterosexual marriage, other languages threaten English. (I agree that English is clearly under siege, but the threat is not from other languages, rather, it’s from English speakers themselves incorrectly conjugating verbs and confusing nominative and accusative pronouns.)

It may be no accident that “Tower of Babel,” the tidy, three-word phrase used to describe the “threat” has biblical origins. According to traditional interpretation, the construction of the tower was an act of hubris by men who wanted to leave their mark on the earth. “[N]ow nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do,” God says in Genesis 11:6-7. “Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.” So if the multitude of languages came about as God’s punishment, we certainly can’t blame today’s pious Christians for our inability to understand each other.

Of course, every pious Christian who laments this sad state of affairs seems to regard his own language as God’s preference. In fact, echoes of other-language disdain are not confined to the United States. When I lived in Spain, I encountered a curious turn of phrase, hablar en cristiano (“to speak in Christian”), an expression that in modern times simply means, “to speak clearly.” While now a quaint, and generally secular expression, the phrase finds its origins in medieval Spanish religious intolerance toward the Jews and Moors.

Likewise, under Francisco Franco’s program of National Catholicism, Spain wrote language censorship into law in 1941. While the rest of Europe subtitled foreign films, all audiovisual products entering Spain were dubbed over in Castilian Spanish lest a French-, German-, or English-speaking Spanish moviegoer understand risqué—or political—dialogue. A rewritten, more wholesome dialogue could then easily replace any objectionable exchanges between the characters. (Dubbing, as a preference to subtitling, remains to this day, although the naughty dialogue is no longer rewritten but rather embraced.)

As it was in medieval and Franco’s Spain, and as it is in the present-day United States, otherness is scary. The known trumps the unknown and the familiar, the mysterious—whether the strange thing in question is a religious icon or a foreign phoneme. Clearly, language, culture, and religion are intimately yoked. Religious tolerance sounds like a pie in the sky when restaurant owners with immigrant clientele implement “English-only ordering policies” or mayors encourage boycotts of fast-food chains that display Spanish-language billboards. It’s bad enough that private companies are discouraged from using tactics to increase their customer base; states across the country have invoked various “English-only” laws and bills are always being reintroduced in the U.S. Congress to make English the official national language. Even the most enlightened among us nod respectfully as the talking heads describe Islam as a religion of peace, but can’t quite get past Islam’s sacred language sounding like random glottal noise.

Is it possible that linguistic tolerance has to precede religious tolerance? Even the most philistine thinker knows that camaraderie begins with words: rewarding requests with responses, having our own utterances, however trivial, rewarded with acknowledgement. Anyone who has ever learned to ask for the toilet or a beer in a second language has felt the uncanny welling-up of warm fuzzies upon receiving the requisite response from his query. Likewise, nary a woman alive is numb to the enchantment of a heavily accented and fumbled remark about her beauty. Savvy advertisers make vegetables and Chihuahuas talk. Sponges and purple dinosaurs talk to kids. Even Koko the gorilla was just another cute mammal until she learned sign language, seducing us with words and stealing our hearts with articulate phrases. Ultimately, her consummate cuddliness was just icing.

Love may be the universal language, but, more appropriately, language is the universal love. After all, it allowed our ancestors to usurp the mammalian throne and to pass on the spoils as every human’s birthright. Plenty has been written about how encouraged we are to talk, from the moment we emerge from the womb. (Were a toddler’s first successful communiqué, “martini, shaken, not stirred, two olives,” would we not be inclined to reach for the vermouth, if only to show the burgeoning sophisticate that his petition was understood?)

What’s more, Desmond Morris, Robin Dunbar, and other psychologists and anthropologists postulate that language developed as a proxy for the primate bonding activity of grooming. Thus learning and using the languages of our fellow earthmates could conceivably be a way to mutually pick fleas off the back of the “global village.” Amazingly, vowels and consonants can and almost always do implant themselves in a fecund infant brain and eventually sprout polysyllabic words and cogent sentences. A vast plain of moldable virgin neurons lies ahead for the acquisition of a second or third language. It would follow that demystifying linguistic diversity opens the door to demystifying religious and cultural diversity.

I admit, language education may be a naive or mawkish solution to the world’s problems, but I suggest it nonetheless to help ferry our dying tolerance back across the River Styx. The altar of social camaraderie is cluttered with saccharine offerings and cloying displays of noblesse oblige. Yet none are so simple, poignant, and genuine as the willingness to tie one’s tongue into knots to be understood. By comparison, “diversity training” looks like nose picking.

Perhaps in the end, it’s neither the color of your skin, nor the content of your character. It’s the coherence of your sentence. To sow the seeds of cross-cultural comity, clumsily conjugating a verb may prove more effective than a thousand choruses of Kumbaya.