All Is Calm, All Is Bright

Silent night, holy night

All is calm, all is bright…

Silent night? Absolutely. Holy night? Nearly 2 billion people on the face of our planet would think so. It’s approaching midnight on Christmas Eve, and I am standing absolutely alone in Arches National Park in southeastern Utah. Well, not absolutely alone. There are undoubtedly plenty of other infidels with me—coyotes, desert bighorn sheep, mule deer, and other such creatures—but I neither see nor hear them. Instead, silence permeates the park. All is calm.

The crisp cold air bites my lungs, is warmed briefly, and then returns to its origins in puffs of transient vapors. Silhouetted rock fins and those eccentrically shaped rock columns called hoodoos stand as witnesses to the indifferent artistry of wind and water, etched to random perfection by the ravages of time. Directly in front of me stands one such hoodoo—its pedestal carved by the elements from 165 million-year-old rock of the Carmel Formation. Precariously perched on the top of the pedestal is a fifty-five-foot tall, 3,500-ton sandstone rock, appropriately named the Balanced Rock. Buried beneath my feet are even older rocks of the Jurassic, Triassic, and Permian Periods and beneath these rocks lies a salt bed initially deposited in the Pennsylvanian Period nearly 300 million years ago. I am truly lost in time.

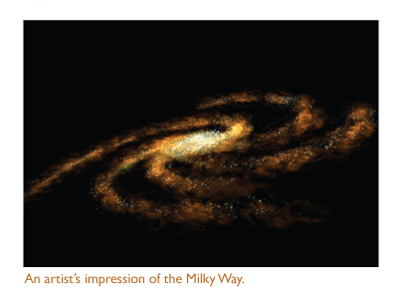

As I turn my eyes upward towards the moonless sky, nearly 5,000 twinkling stars greet my gaze and billions more send out light too faint for my eyes to detect. With so many stars, most of the constellations recede unnoticed into a tapestry of shimmering lights. The disk of our Milky Way Galaxy stretches directly overhead arching its cloudy band of stars from the southeast to northwest horizons. All is bright.

As I turn my eyes upward towards the moonless sky, nearly 5,000 twinkling stars greet my gaze and billions more send out light too faint for my eyes to detect. With so many stars, most of the constellations recede unnoticed into a tapestry of shimmering lights. The disk of our Milky Way Galaxy stretches directly overhead arching its cloudy band of stars from the southeast to northwest horizons. All is bright.

Alone, standing by sentinels of time unfathomable, engulfed by pinpoints of light that have been traveling from their respective sources for more years than I have drawn breath—what better place is there to spend a Christmas Eve? I have come here to be awed—to be inspired. Let Christians have their fanciful story of the virgin birth. I have the reality of nature—terra firma beneath my feet, the ancient rocks before me, and the vastness of the universe with billions of galaxies and billions of burning stars within each galaxy. I am surrounded by those unseen infidels with their trillions of cells, each cell transcribing the appropriate complement of genes for a precise functional role. I am engulfed by molecules made of atoms, which are, in turn, made of protons, neutrons, and electrons, which themselves are made of indivisible quarks and leptons. I am part of this vast cosmos. The carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur atoms that are central components of the organic molecules in my body were generated in distant stars by the fusion of helium atoms. Metals such as calcium and magnesium, which are required cofactors for many of the essential enzymatic reactions currently occurring inside my body and the bodies of my fellow desert denizens, were also created by fusion within the stars. We are literally made of star stuff.

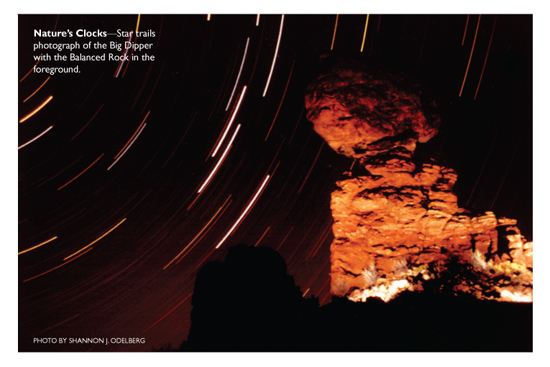

I have come here on this “holy” night not only to be awed and inspired but to try to capture a piece of this inspiration on film. I am especially interested in capturing the concept of time by simultaneously photographing two of nature’s clocks. I circle around the Balanced Rock heading toward its south side. Finding a flat sandstone surface, I set up my tripod. Attached to its head is my trusty Pentax camera equipped with a 50 mm lens and loaded with Fujichrome film. Pointing the camera towards the north-northeast, I frame the shot so that the Balanced Rock will fill the right side of the photograph and the stars of the Big Dipper (part of the constellation Ursa Major) will appear in the center. I set the f-stop to 2 and the shutter speed to bulb, focus on infinity, and depress the cable on the shutter release. After tightening the screw to keep the cable depressed and the shutter open, I slowly move away from the camera, taking care not to inadvertently bump the apparatus. Now I let the earth’s rotation and time do the work.

This imaging technique is known as “star trail photography,” because the light from the stars leaves trails of exposed emulsion on photographic film. As the earth rotates on its axis, the stars appear to move across the night sky from east to west. Because I have pointed the camera toward the northern sky, the stars will appear to move in a counterclockwise circle around the north celestial pole (approximately defined by the star Polaris, also known as the North Star). As the stars “move,” they will continually expose the film as long as the shutter remains open, thus producing an arc of exposed film. The length of the arc is directly proportional to the exposure time. If the exposure time is two hours, for example, the arc will be approximately 30° (one-twelfth of a 360° full circle), given that two hours is one-twelfth of an entire day. By photographing both the Balanced Rock and the “circling” stars, I hope to capture nature’s geologic and celestial clocks in a single photograph.

As I let the earth’s rotation and the lights of the night sky work their “magic” on the film, my thoughts again return to the vastness of space and time. The seven stars of the Big Dipper are known by a variety of names including the traditional set Dubhe, Merak, Phecda, Megrez, Alioth, Mizar, and Alkaid. The closest of these stars is Mizar, which is the middle star of three that compose the handle of the dipper, and the light I’m seeing this Christmas Eve* left that star in 1920 about the time American women acquired the long-overdue constitutional right to vote. After seventy-eight years of intragalactic space travel at the speed of light, the photons finally reach the earth where they activate the photoreceptors in my eye and the silver halide grains in the film’s emulsion.

My mind races to figure out how many miles the light has traveled during its seventy-eight-year journey. Sixty seconds in a minute, sixty minutes in an hour, twenty-four hours in a day, and 365.25 days in a year. Multiply the number of seconds in a year by seventy-eight and then multiply by the distance light travels in a second (approximately 186,000 miles), and I will have the answer. By rounding off numbers and taking advantage of scientific notation to simplify the calculations, I eventually arrive at an estimate of about 4.5 x 1014 miles, or 450 trillion miles (the actual number is 460 trillion miles). The light from Mizar that is now activating my photoreceptors and exposing my film has traveled 460 trillion miles through space!

Dubhe, which together with Merak forms the outside of the bowl of the dipper and points toward Polaris, is the most distant Big Dipper star at 124 light years. But these are relatively close stars compared to the farthest stars we can see with our naked eye, some that are nearly 4,000 light years away and one, V762 Cas in the constellation Cassiopeia, which is estimated to be a distance of nearly 15,000 light years from Earth. But even these stars are relatively close to us compared to the stars in other galaxies. For example, the only galaxy that can be seen by the naked eye from Arches National Park is M31, better known as Andromeda, which is a mind-boggling 2.5 million light years away.

Dubhe, which together with Merak forms the outside of the bowl of the dipper and points toward Polaris, is the most distant Big Dipper star at 124 light years. But these are relatively close stars compared to the farthest stars we can see with our naked eye, some that are nearly 4,000 light years away and one, V762 Cas in the constellation Cassiopeia, which is estimated to be a distance of nearly 15,000 light years from Earth. But even these stars are relatively close to us compared to the stars in other galaxies. For example, the only galaxy that can be seen by the naked eye from Arches National Park is M31, better known as Andromeda, which is a mind-boggling 2.5 million light years away.

Turning abruptly from celestial wonders to the immediate task at hand, I realize that if I simply leave the shutter open and let the reflections of the natural light expose the film, I will only obtain a silhouette of the Balanced Rock against a star-laden night sky. Although such a photograph can be quite dramatic, my purpose this evening is not only to capture the celestial clocks in the sky but also to capture the geologic effects of time in the rock formations that surround me. I reach inside my camera case and pull out a flash unit. I set the ISO for 50 and the manual power ratio on full. Boldly, I step in front of the lens, realizing that as I move within the field of view, the momentary faint reflections from my body won’t register on the film. For a moment my mind drifts and I relish the thought of invisibility—being able to travel without notice among the hoodoos and fins rising before me—an explorer observing these magnificent works of nature without leaving the scars of my footprints behind. Alas, this is not the case, and as I make my way toward the towering hoodoo, I must carefully avoid the rocks protruding from the ground lest I unwittingly stumble and plant my face in an unseen bed of prickly pear cacti. Approaching the giant sentinel of time, I turn on the flash and raise it above my head. I point it toward the rock perched about seventy-five feet above me, and I fire. While waiting for the flash to recharge, I walk around the base of the pedestal and reposition myself for another flash that will expose a different portion of the perched rock. I fire the flash again. I repeat the procedure and fire again. And again—until I have repeatedly exposed all portions of the underbelly of the behemoth bulb by firing about twenty-five flashes at various angles.

As I retrace my steps back toward the camera, my thoughts turn toward the geologic forces that generated this masterpiece of nature. About 300 million years ago, a land-locked sea formed when it became separated from its parent ocean to the west. Over the course of millions of years, the sea evaporated, depositing salt and minerals that later compressed under the pressure of overlying deposits. The ocean to the west waxed and waned as the environment changed due, in part, to shifting latitudes dictated by plate tectonics. This waxing and waning of the ocean, which continued through the Cretaceous Period up to at least 80 million years ago, produced a geography that varied between tidal flats and sand dunes. The deposits from the sand dunes produced the Navajo and Entrada Sandstone layers, while the Carmel Formation lying between these two layers was deposited during a time period when the region was covered with tidal flats (some 165-170 million years ago). As the sand from different layers was compressed from the weight of later deposits, it hardened into rocks. Between 80 and 15 million years ago, the weight of the overlying rock caused the plastic salt beds beneath to move and push upward, buckling the overlying layers. The salt also squeezed through fault lines in the rock producing salt anticlines. Water erosion of the salt collapsed the rocks leading to sunken valleys and escarpments that are evident throughout the region. This collapse caused the rock layers along the rims of the valleys to roll over the edge, producing deep fissures within the rock. Over the past 15 million years, wind, water, ice, and temperature fluctuations differentially eroded away the rock within these fissures and the overlying deposits to create the fins, arches, and hoodoos for which the park is famous.

The Balanced Rock, that magnificent hoodoo on which my camera is currently trained, is a product of this differential erosion. The monster rock is composed of hard Entrada Sandstone, which is more resistant to the ravages of the elements than its pedestal, formed from the more fragile Dewey Bridge Member of the Carmel Formation. This differential resistance to erosion has produced a hoodoo with a 3,500-ton rock precariously perched on a pedestal with a relatively small neck. The same nearly imperceptible creative forces that produced this majestic structure will one day cause its catastrophic collapse. Such imperceptible forces gradually weakened a portion of another famous structure in Arches National Park, Landscape Arch, which led to the catastrophic loss of three large pieces of rock—one in 1991 and two other pieces in June 1995.This natural geologic process is known as exfoliation and can produce dramatic changes in geography. Indeed, the geologic clock continues to tick.

By the time I reach the camera, about forty-five minutes have elapsed since I first opened the shutter. My intent is to keep the shutter open for a full hour, which leaves me fifteen minutes to bask in the glory of the cold winter night. My thoughts continue to focus on the immensity of time spread out before me as a celestial and geologic feast. I begin to think about those deep sky objects that can only be observed through the ingenuity of human invention. These distant objects are beyond the capability of my retinas to detect without the aid of a telescope. I start to compare the geologic events that shaped Arches National Park with the unseen celestial lights that surround me. Somewhere out there in the vast cosmos, the light from a galaxy 160 million light years away is striking the film in the camera. Although the film will not register this encounter, it will register the reflections of my electronic flashes bouncing off the 160 million-year-old Balanced Rock. The imperceptible light left that distant galaxy at the same time that the Entrada sand dunes were being deposited. And though I can’t visually observe the intersection of these two events, which have spatially distant yet simultaneous origins, I can readily imagine it, and again, I marvel at the interconnectedness of the vast cosmos.

An hour has now passed since I opened the shutter, so I amble over to the camera and twist the screw on the cable release counterclockwise. The distinctive grate of the closing shutter greets my ears, confirming that the film has been exposed. Now comes the seemingly interminable wait for the film to be developed. Only time—a mere blink of the eye when compared to the events my mind has been contemplating this evening—will determine whether I have successfully captured a suitable image of nature’s clocks. Whether this part of my mission is a success or not, the time I have spent among the hoodoos and fins gazing at the distant stars will provide me with unforgettable memories. As Christians around the world celebrate the mythical virgin birth of their Messiah, I have chosen to celebrate the grandeur of nature. As believers marvel at the “miraculous” star of Bethlehem, I marvel at the nature of the twinkling stars above me. And as for the Rock of Ages? I have no need for such a crutch. My feet are firmly planted on solid rock from the age of dinosaurs and these tangible rocks function both to give my body more than ample support and my mind more than enough to contemplate.

Nature never ceases to amaze me. I am humbled by my relative insignificance within the vast universe. I am really nothing but a speck of sand within this cosmic sea. And yet, I exist. I think. I reason. I explore. I learn. Evolutionary forces of chance and natural selection have “conspired” to bring me to this moment, and I revel in my paradoxically insignificant significance. Silent night, “holy” night—all is calm, all is bright.

*The star trails photograph described here was taken on December 24, 1998.