Black Churches and Blue-Eyed Jesuses

This article is adapted from Chapter Five of the author’s 2011 book, Moral Combat: Black Atheists, Gender Politics, and the Values Wars.

The first few minutes of the revival movement film Elmer Gantry (1960) are a paean to the spit and gleam of Burt Lancaster’s Klieg-light teeth. Dancing shamelessly like a character unto themselves, they tell you everything you need to know about twentieth-century divinity and the meteoric rise of the evangelical shaman as an American idol. Based on Sinclair Lewis’ satirical 1927 novel of the same name, the film chronicles a midwestern rogue’s pursuit of Jesus, Inc., represented by a beatific revivalist preacher by the name of Sister Sharon Falconer (played by Jean Simmons).

Lancaster tears into the title role with lupine brio. Barely ten minutes into the film, a dirty and disreputable Gantry, freshly sprung from a hobo brawl on a musty boxcar, lands at a Negro church. Gantry’s own brand of religion marches lockstep with sex, lies, moonshine, and doe-eyed indolence. Before his date with destiny he staggers around, selling cheap vacuum cleaners, toasters, and any other sundry fare he can get his hands on. He’s desperate for a quick fix, a ticket out of obscurity. Is there no better place for a miscreant white man to jam his foot in the door of redemption than a Negro church?

If Hollywood cinema is America’s shepherd, there isn’t. In the 1980 film The Blues Brothers, ex-cons Jake and Elwood Blues (John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd, respectively) embark on their back-flipping “mission from God” with a send-off from preacher James Brown and choir member Chaka Khan. Robert Duvall’s turn as a charismatic preacher in the 1997 film, The Apostle, begins and ends in steamy clapboard black churches. In Jim Crow America, white people enter black sacred spaces strategically yet innocently, and their presence is seemingly unquestioned. They enter and are indelibly transformed, their souls becalmed—the lynch rope that would surely greet a black interloper in a World War I-era white church unthinkable.

In Elmer Gantry, Lancaster hears the peals of “On My Way to Canaan’s Land” as he walks along the train tracks. He follows the sound and enters the church with the service going full bore. The singing stops as he enters. Gradually, as he lends his powerful tenor to the song, the all-black congregation’s initial wariness gives way to some kind of acceptance. Of course, images of black folk rapturously belting out gospel songs are standard fare in American nostalgia. But the Gantry scene intrigues because of the striking figure of a little girl standing next to him in the congregation. She gives him the once over, her disrupted body language conveying caution and bewilderment with the inimitable honesty of a child. This quizzical little girl is the visual anchor of the scene, the adults swept up in euphoria—grinning, clapping, and singing with soulful abandon. Again, the Negro church is a crucial point of spiritual entry for the dissolute white man. The embodiment of natural, primitive spirituality and devoutness, its congregants are an important space of projection for Gantry’s personal journey from ignominy to (partial) redemption. Gantry later becomes Sister Sharon’s spiritual lieutenant and lover and a quasi-folk hero in the lily white, corn-fed world of Pentecostal tent revivals. Tellingly, there are virtually no other people of color featured in the entire movie after the Negro church scene.

Thus, the little girl serves as a silent commentator on the reality of black subjectivity in the midst of racial apartheid. Yet she is also a symbol of the complex faith rituals in black communities. These rituals are a tacit part of the traditional African-American upbringing. The camera frames her shock at the white interloper’s presence but it also suggests her potential defiance. Even in the sanctuary of the church, black children were taught that whiteness signified power; that white space carried a special authority and terror, and that Jesus looked not unlike Elmer Gantry.

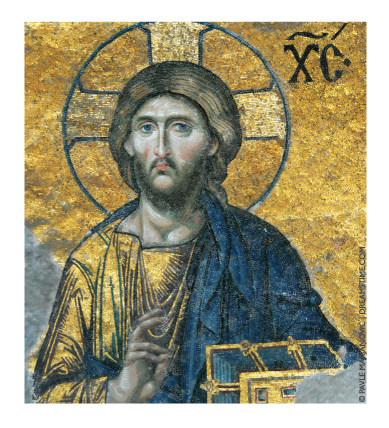

Blue-eyed Jesuses float spectrally from my own childhood. It was a period in which the Los Angeles Police Department’s murder of a single black woman in her own home solidified the city’s police-state status. In the still smoldering political climate of the 1970s, the walls of friends and relatives’ homes were often graced with the somber “trinity” of Martin Luther King Jr., John F. Kennedy, and an ethereal blue-eyed Jesus. Still, attending all-black elementary schools in South Los Angeles, discussions of faith were not that frequent; it was simply presumed that all black folk were religious in some respect. Because of the prominent street presence of black Muslims, other religions were fleetingly visible, yet Christianity was unquestioningly the default position. Coming from a rare secular African-American household, dominated by a formidable literary and historical library, the Bible was something I was only cursorily familiar with. During a brief foray into world religions, my father brought home a copy of the Koran, but the Bible was essentially an alien and mysterious document. (Fleeting fascination with a storybook depiction of Moses’ epic battle with the Pharaoh and the parting of the Red Sea was one of the few vivid childhood memories I have of the majesty of Old Testament lore.)

Blue-eyed Jesuses float spectrally from my own childhood. It was a period in which the Los Angeles Police Department’s murder of a single black woman in her own home solidified the city’s police-state status. In the still smoldering political climate of the 1970s, the walls of friends and relatives’ homes were often graced with the somber “trinity” of Martin Luther King Jr., John F. Kennedy, and an ethereal blue-eyed Jesus. Still, attending all-black elementary schools in South Los Angeles, discussions of faith were not that frequent; it was simply presumed that all black folk were religious in some respect. Because of the prominent street presence of black Muslims, other religions were fleetingly visible, yet Christianity was unquestioningly the default position. Coming from a rare secular African-American household, dominated by a formidable literary and historical library, the Bible was something I was only cursorily familiar with. During a brief foray into world religions, my father brought home a copy of the Koran, but the Bible was essentially an alien and mysterious document. (Fleeting fascination with a storybook depiction of Moses’ epic battle with the Pharaoh and the parting of the Red Sea was one of the few vivid childhood memories I have of the majesty of Old Testament lore.)

So when I was practically cornered and sharply questioned one day by “Angie,” a school bus acquaintance, about whether I attended church on a regular basis I was embarrassed to confess that I didn’t. The questioner had more than an impartial interest. She was a pastor’s daughter and a sixth-grader well known for her sage counsel and commentary on the knuckleheaded exploits of back-of-the-bus screw-ups. My non-churchgoing flippancy and oddball upbringing were greeted with eye-rolling incredulity. Seeing a lost soul and potential convert, she recommended that I check in with the Bible and begin to “talk” to God. Painting a picture of God’s benevolence and 24/7 accessibility, she encouraged me to practice this new form of supernatural correspondence as soon as I had a moment to myself.

I have vivid memories of attempting this experiment in the privacy of my own room. I balanced an inward sense of the futility of the enterprise with an earnest hope that it would yield something. If “God” was in fact omniscient, why would I have to talk with him, her, or it? Why wouldn’t my deepest thoughts and desires already be known? And how did this relate to my own actions? How would I, in fact, know that I’d been heard or acknowledged? And what about that jealous, unforgiving God of the dimly remembered, interminable sermons I’d had to sit through at my grandparents’ church? Wouldn’t he be pissed off at my fairly new and grudging entry into his global 24/7 psychic Tower of Babel? For ten years, while all those other folk were praying and going to church and dutifully dropping their tithing envelopes into the collection plate, I was morally adrift in a loving household filled with books. This, then, is the rub for the nonreligious and nontheistic. Why is it necessary for children raised in secular homes to be indoctrinated with the codes and mores of any given religion when they are already steeped in a moral life? And why would anyone want to be associated with a religion that made such an arbitrary and artificial distinction, condemning children as sinners? Why, indeed, would children be compelled to profess belief, especially when they look around them and see that the world is overpopulated with adult believers flaunting their immorality?

So “talking” to God in the safety of my room, I was unmoved. In the pell-mell world of elementary school cliques and neighborhood bullies, every day was a lesson in moral judgment. The temptation to lie, cheat, steal, and/or knock someone upside the head for no apparent reason was present at every turn. Prayer only offered a quick and dirty escape hatch from the messy human circumstance of immoral acts. Without the reinforcing compass of God, my evangelist friend, Angie, worried that I would fall into an abyss of amorality. I would be paralyzed, unable to distinguish the delicate ethical nuances of sticking a grasshopper leg in the ear of a snoozing classmate or informing on a neck-craning cheater who was cribbing answers from my spelling test.

What would it mean for children to view morality within a context in which the common humanity of different individuals is not only emphasized but actual value is placed on the complexity of those differences?

For children in a Christian tradition, the insularity of prayer is the linchpin to becoming moral. Prayer—atomized, isolated, viewed as one small drop radiating through a big God-roiled pool—is something that even little kids can do with minimal effort or expenditure. Prayer becomes a moral device, a tool, and a treadmill. If I send out well wishes for a certain person, cause, or catastrophe, the thinking goes, it will reverberate and have some tangible effect. And so prayer gives one a temporary pass for not actually doing something in the real world or fundamentally changing one’s perceptions of “others.” For a few inexpensive moments a day I can plug my chip into the circuit board of the divine, holding out hope for resolution. I can pray that God will cure the HIV-infected kid in my fifth-grade class whose homeless parents can’t afford to buy food much less health insurance or even the latest designer shoes. I can then go blithely on my way without having to linger on whether there actually is a higher power that can make such a whiz-bang change. I can weigh the inequitable human social order with the mystery and moral justice of the divine. For if this social order is not human inspired, then naturally there must be some moral reason why the child suffers. There must be some causal connection between the child’s condition and the moral failings of the parents. The hand of God must be somewhere, benevolently pulling the strings.

I have a vivid memory of the first time I became aware that children could die. It was early evening in the leisurely dusk of summer. After eating with my mother at a local coffee shop, we passed by a newspaper vending machine outside. A child victim, kidnapped, murdered, and disposed of like garbage, stared ominously out at me from the front page of a newspaper in grainy black and white. I remember my sense of horror when my mother told me that the child, who was approximately my age, would never see his parents again. Associating death with old people, I was stupefied by this seeming contradiction. Alone in my bed that night, my friends’ prayer-saturated social universe smacked me down, and I wondered how “God” could have countenanced such unspeakable evil.

Decades later there is an aching space where this child’s life would have been, his personhood, his bundle of tics, idiosyncrasies “frozen” at abduction. Violent death by homicide at an early age is a grim reality for many youth of color. Gangsta rap romanticizes it and dishes it up for the voyeurism of white suburbia. Mainstream media ignores it or relegates it to social pathology. Every semester when I ask my students if they’ve had a young friend or relative die violently at least half will raise their hands. Their tattoos, notebooks, and Sidekick phones are filled with vibrant mementoes for the dead. Such are the killing fields of disposable youth. It is not necessary to go to Iraq, Afghanistan, or some other theatre of American imperialism to experience this devastation. And yet, in urban communities there is God at the precipice, dangling children and fools over the side, manufacturing faith.