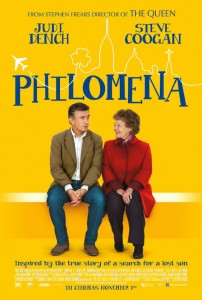

Movie Review: Philomena

In Fred Edwords’ review of Philomena, a film in theaters now and the subject of Oscar buzz, he spotlights its unabashed humanism.

Nominated for three Golden Globe awards—Best Motion Picture, Drama; Best Actress in a Motion Picture, Drama (Judi Dench); and Best Screenplay, Motion Picture (Steve Coogan and Jeff Pope)—Philomena is a major theatrical release that belongs squarely in today’s era of emergent humanism. For not only is one of the film’s two protagonists a forthright atheist (including the actor/screenwriter/producer who plays him), but the overall message is one of truth over dogma and humanity over religious oppression.

Yet all of this isn’t allowed to dominate to the point of becoming propaganda, as I’ve seen happen in a few earlier film and literary efforts that have crossed my path. Exuberant godless writers, eager to put their best humanist foot forward and advance their values, almost always place message so far above story and characterization that the result ends up more like a dialogue of Plato than a compelling drama. Not in this case.

Here we meet Martin Sixsmith (Steve Coogan), a journalist and atheist at a low point in his career, who is introduced to Philomena Lee (Judi Dench), a devout Roman Catholic with a secret. What she has to tell, and the investigation it will lead to, has all the makings of a great human interest story. But Martin feels that such writing is beneath him, and that Philomena’s religiosity and shallow intellect make her hard to take. It’s only because he needs the money that he somewhat grudgingly sets out on the project.

Philomena’s story, however, is heart wrenching (and based on real events, as published in the 2009 book The Lost Child of Philomena Lee). A half century earlier, in the aftermath of a sexual encounter she still remembers fondly, she’d given birth to a son. But this happened in Ireland and Philomena, because she was an unwed mother, was put in a convent where she was forced to work long hours in exchange for her care. Moreover, her boy was taken from her and, when three years of age, was sold to an American couple.

So Martin and Philomena begin their investigation at the convent. When this reaches a dead end, they follow leads to the United States. There they discover that her son became a prominent Republican official. He was also gay, something that Philomena had understood about him early on. But what she most wants to know is whether he ever thought of her, if he ever tried to find her. And there the drama becomes more gripping, leading to unexpected twists and turns that take Martin and Philomena back to the convent and to a confrontation that pits humanist moral outrage against Christian forgiveness.

In the end both Philomena and Martin are changed by the experience, each gaining greater insights, not to mention a better understanding and deeper appreciation for each other. But one annoying and endearing characteristic of Philomena remains steadfast—and a constant source of comedy relief: her enthralled enjoyment of romance novels, the predictable plots of which never fail to surprise her.

After you’ve seen this movie you’ll arrive at a place where you can say to any who might ask, this is what a quality humanist film looks like. When the theater lights come back on, the experience isn’t over. Viewers are left with much to talk about, and feel. It is for experiences like these that film lovers gather in groups for a cinema night, followed by intense conversations in a coffee shop afterwards to explore the ramifications and discuss the controversies. They can also argue over the characters, who in this film are wonderfully imperfect and therefore human. There are no unsullied heroines and heroes here. They have faults and blind spots, and can be downright annoying, just like real people. And that makes them worth talking about until closing time.