Book Excerpt: Tech Agnostic: How Technology Became the World’s Most Powerful Religion, and Why It Desperately Needs a Reformation

Excerpted from Tech Agnostic: How Technology Became the World’s Most Powerful Religion, and Why It Desperately Needs a Reformation by Greg M. Epstein. Reprinted with permission from The MIT Press. Copyright 2024.

One could write a book about what humanism even is, and indeed I already have. Along with earlier meanings, the word has been used for just over a century now for the study and practice of, as I explained in a book that attempted to provide the shortest possible definition with its title, Good Without God. But for now, let’s sum the concept up with a line coauthored by Carl Sagan, the great astrophysicist and science educator, and Ann Druyan, best known as Sagan’s wife and the producer of his legendary PBS show Cosmos: “For small creatures such as we, the vastness is bearable only through love.”

This scientific poetry is key to understanding the best of modern humanism. Sagan and Druyan brought together the human longing for explanation that animated the first lines of the Hebrew Bible (“In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth”) with the compassion that the Buddha felt when he said, “Radiate love towards the entire world without hindrance, hostility, or animosity” and the devotion that early Muslims experienced when they decided to name their religion after the notion of submission to a force much greater than oneself.5 Sagan and Druyan’s statement also draws on the power of human affection, care, and intimacy that inspired not only theologies of Jesus on the cross but the ancient Zoroastrian hymn from the Old Avestan language of two millennia ago: “I know in whose worship there exists for me the best in accordance with truth. It is the Wise Lord as well as those who have existed and still exist. Them all shall I worship with their own names and I shall serve them with love.”

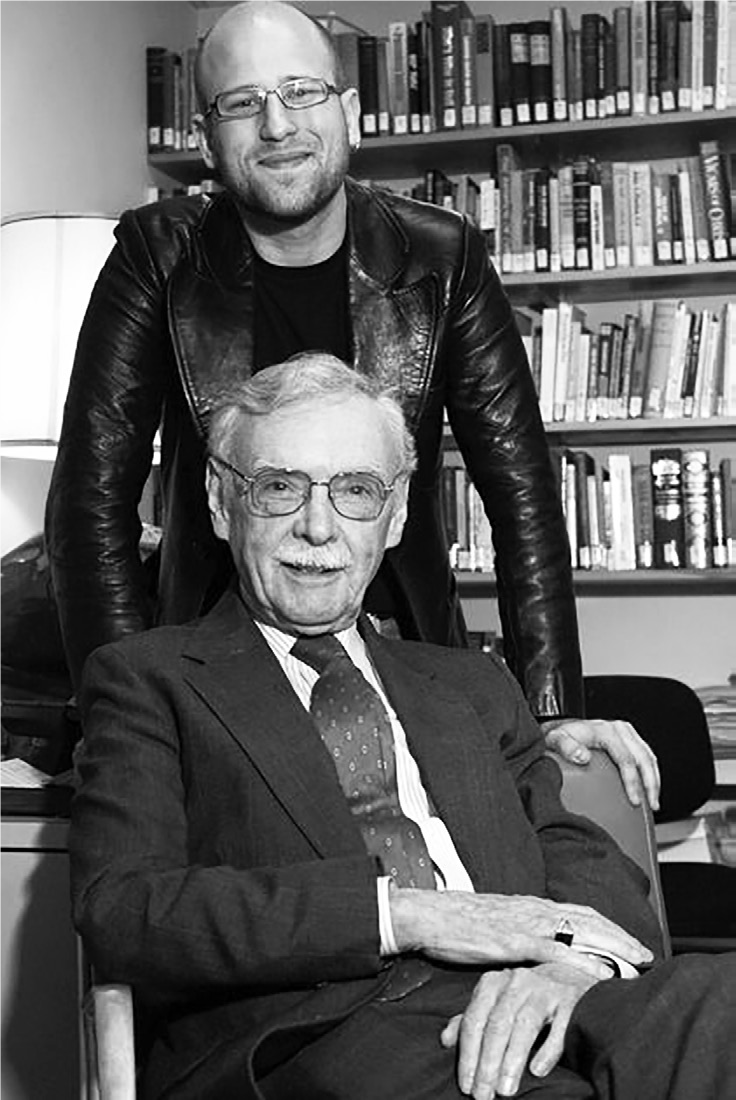

Tom Ferrick, with the author, from the Boston Globe, 2005. Photo by Zara Tzanev.

Humanism is, in other words, a nonreligious tradition that is a sociological equivalent of religion. Most humanists would describe themselves as atheists or agnostics, but the ism points toward something beyond that: humanism focuses on our beliefs rather than our disbeliefs. It acknowledges the value, and the frailty, of our humanity— because we are, as the phrase goes, “only human.”

Humanism, in practice, is also a refusal to say religion is good or bad, yes or no. While nontheistic, a fancy term for atheist or agnostic, you can disagree with humanists theologically and still be considered just as good a person as anyone else. (Indeed, you should believe whatever your conscience dictates and whatever inspires you to treat others— and yourself— with dignity, decency, and love.) Like art and psychology and social justice work, humanism is a way of taking the world as we find it, in all its ugliness, and making it more beautiful. Which is exactly why the principles of humanism, as an alternative religion, transfer to the world of tech and of the tech religion. Because in a world of too much false belief and unquestioned dogma, with too many oppressive hierarchies, too much tribalism and cultish devotion, and far too many threats of apocalyptic destruction, the tech religion needs . . . tech humanism.

Fortunately, such a thing exists.

Kate O’Neill, founder of KO Insights, author of Tech Humanist and A Future So Bright.

Kate O’Neill, known professionally as the “tech humanist,” is a writer, commentator, and founder and CEO of KO Insights, a strategic advisory firm she describes as “committed to improving human experience at scale through more meaningful and aligned strategy.” She eagerly recalls how the first time she saw the Internet, not long after graduating from college with a linguistics degree in the early ’90s, she got chills down the back of her neck. This is going to change everything, she immediately thought. She dove in and now has a long résumé with serious tech bonafides, including creating the first content- management role at Netflix and developing Toshiba America’s first intranet. But O’Neill is also a humanist in the sense of being a nonreligious believer; a person who believes human beings created religion, not vice versa; and who focuses her life on how to be and do and experience good without traditional theistic belief. She describes with pride, for example, how the Catholic faith she was raised to uphold fell apart in high school. Her mother told her, “I hope when you go to college, you won’t read too much and lose your faith like your aunt Ruby did.” And when the pope proclaimed that women would never be ordained, her dad called her to say how sorry he was, and how much he knew it hurt her. Like my late mentor Tom Ferrick, Kate had wanted to believe in Catholicism as a— or rather the— redemptive force in the world. But she was also a principled feminist and someone who believed in the concept of truth itself. The Catholicism she had wanted to imagine, the pope’s decision taught her, was not the religion that actually existed. Her faith, like Tom’s, collapsed because she preferred the uncertainty and instability of a continuing search for values she could believe in to the perhaps more secure path of allegiance to an institution she no longer saw as worthy.

In her book, O’Neill defines tech humanism as “recognizing that we encode ourselves into machines; that what we automate will scale; that we need to be aware of what we encode and scale.” The idea, in other words, is that humans create technology, not vice versa, and the similarity to how humanists talk about religion is not accidental. Like agnostics or religiously unaffiliated people who find humanism as a positive answer after not knowing how or where to move forward from off- balance disbelief, O’Neill’s business clients sense that some of the tech around them is becoming inhumane but don’t know what to do about it in a profit- driven world. The tech humanist approach she offers them can be a lifeline.