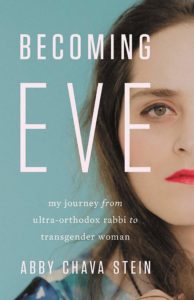

Book Review: Becoming Eve: My Journey from Ultra-Orthodox Rabbi to Transgender Woman

BY ABBY CHAVA STEIN

SEAL PRESS, 2019

272 PP.; $28.OO

The dedication of Abby Chava Stein’s autobiographical book, Becoming Eve: My Journey from Ultra-Orthodox Rabbi to Transgender Woman reads: “To my dear son, the love of my life, Duvid’l, to long years.” This protestation of love for her son sets the stage for a tale of her own parents’ rejection of their transgender daughter. She follows this with a quote from Song of Songs, a text found at the end of the Tanakh, the Hebrew Bible. It reads: “Mighty waters cannot quench love; rivers cannot sweep it away.” As Stein illuminates in the story of her departure and ostracism from the ultra-Orthodox Jewish community in which she was raised, dogmatic religion can contain love, but love should not and cannot be contained by dogmatic religion.

Becoming Eve is a story of identity told as a coming-of-age tale. Abby Chava was given the name Yisroel Avrom at birth and raised as a boy. The book recounts the author’s struggle with an identity that was dictated by the ultra-Orthodox society which placed labels on her gender and her philosophy of belief.

She was raised as an Hasidic Jew and is a direct descendant of the Polish healer Israel ben Eliezer, also known as Baal Shem Tov and regarded as the founder of Hasidic Judaism. A subsect of Orthodox Judaism, Hasidism is known for its insular communities that emulate Eastern European Jewish shtetls, not only the style of dress and cuisine but especially the strictness of their Judaic practice. In order to achieve this, they seclude themselves as much as possible from the “secular” world around them. In addition, Hasidism abounds with superstitions and strict rules of conduct.

Abby Stein né Yisroel Avrom grew up with almost no access to modern culture or English language instruction. Boys like Yisroel, descended from a line of revered rabbis, were expected to become rabbis and leaders themselves. They exclusively spoke Hebrew and Yiddish, received very little education in practical subjects, and spent the majority of their time exclusively studying the Torah.

Orthodox Judaic culture is very much predicated on binary gender roles; nonconformity to these roles is not an option. LGBTQ issues are not so much derided as they’re simply nowhere in the realm of awareness. So Yisroel certainly had no information and no way of knowing that there was even such a person as a transgender individual. Yet, as Abby writes in the introduction, she didn’t understand how it could be, but she knew very early on and for certain that she was a girl.

The ultra-Orthodox relationship to physical sex and marriage described in Becoming Eve is fascinating. As a young boy, Yisroel is taught to never touch himself and would only be told about the act of sex by a marriage coach right before his wedding. This is also the one area where culture trumps the letter of Jewish law. Adultery, and even polygamy, are technically permitted by the Torah but culturally unacceptable.

Of course, Yisroel discovers things along the way as he reads and even experiments with a homosexual relationship. It is a reasonable assumption that there is much elicit sexual activity in the Orthodox community that goes unreported. This begs the question: If homosexuality, is forbidden by Jewish law but culturally acceptable, why is it not permitted?

The book follows Stein’s early life through her wedding, on to her leaving the Orthodox community, and finally coming out to her father. She takes us through her home life, her experiences at school, her marriage and its consummation, the birth of her child, and all the conflicting emotions and mental states that accompanied these things as experienced by a girl who was raised as a boy and a woman treated as if she were a man.

The story is as much an exploration of religion as it is of gender. When the young Stein finally finds the opportunity, she reads forbidden books, from Jewish texts and philosophers that spark questions about God to, eventually, modern-day atheists. She finds passages from her own ancestors and others that even justify her gender identity “Jewishly” to her. She goes what ultra-Orthodox communities call “off the derech” (off the path), becoming an atheist and leaving the community with the help of a nonprofit that assists people who want to leave ultra-Orthodox Judaism.

Given all of this, one might expect the book reflects a justified anger or resentment, however Stein tells us in the beginning that there is “no agenda, just my story.” And she keeps that promise. Without holding back the honest facts about life as a transgender woman in a gender-segregated society, she also conveys the sense of “safety, belonging, and love that growing up in a religious, even cultish, community offers.”

The book is a love letter of sorts to Stein’s family and the Hasidic community. We never feel love is lost—in fact, when we get to the epilogue where Stein comes out as transgender to her father, we feel love amplified and sense her desperate hope that the family and community she loves so much, and who certainly love her, will welcome her new identity. It’s no spoiler that they don’t, or rather they can’t. Her father leaves some hope when he says he’ll let her know if they can ever speak again.

Stein does find a loving family in a Jewish Renewal congregation and within the LGBTQ community. With the support of the progressive rabbi of her new congregation, she also finds a new perspective and renewed love for Judaism. She is given a new name and a new lease on life.

It is an Orthodox Jewish tradition for a child’s name to include the father’s name. When she was given her now deadname, it included her father’s—Yisroel Avrom, son of Menachem Mendel. Stein reaffirms her love for her family of birth with her new name, which includes both her father’s and her mother’s—Avigail Chava, daughter of Menachem Mendel and Chaya Sheindel. The Hebrew name “Avigail” roughly means joy; “Chava,” which is “Eve” in English, means life.

Returning to the dedication pages, the author offers a quote from a distant relative who founded the Hasidic movement, the Baal Shem Tov. It is incredibly prophetic and sums up the sentiment of the book: “Let me fall if I must fall. The one I will become will catch me.”