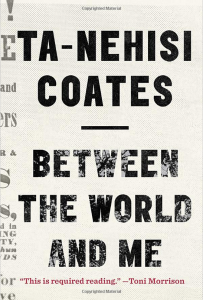

Book Review: Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates

Ta-Nehisi Coates’s new book Between the World and Me is a short one—really a collection of three essays, designed as a letter to his fifteen-year-old son that takes the form of a poetic autobiographical account of Ta-Nehisi’s unrelenting racial consciousness.

What makes this work a novel addition to African-American literature is the premise upon which he begins. The story starts in the unlikely family into which he was born: his father was a part of the Black Panther movement and who filled his home with voices of the black nationalist movement; his mother held a constant and at-times violent fear for her black child and challenged him to investigate the world around him through reading, writing, and critical appraisal. Confined to the crushing ghettos of West Baltimore, both parents believed it best to create a nonreligious household built upon an independent, and possibly futile, search for truth. It was this unique mixture that lead Coates to write:

To be black in the Baltimore of my youth was to be naked before the elements of the world, before all the guns, fists, knives, crack, rape and disease.

On those streets, blackened by the oppressive heat of poverty, Coates had only his human dignity to hold on to. With the comfort of the state security apparatus nowhere to be found, Coates and his peers were left to suffocate under the constant threat of street violence, the constant fear of being moved down another rung in the pecking order. For these kids, violently maintaining their dignity, showing that they are not “punks” to be used and abused was all but necessary for survival, thus creating a culture based not upon belief in future successes, not in thoughts of the inevitable grandeur to come, but upon a never-ending fear—the all-encompassing fear that he, like so many brothers before him, would not live past the age of twenty-five.

Reading the passages, the fear is palpable. You can see it in his poetic urgency. But Coates had more parental support than most and was able to channel this fear into rabid investigation, investigation of himself and the world around him. It is an investigation that’s like Malcolm X’s during his imprisonment and subsequent Islamic enlightenment. In fact, Malcolm X was Coates’s greatest idol growing up. Coates recounts a vivid scene of himself as a young black boy strolling down the streets, headphones on, Walkman in hand, listening in rapture to Malcolm X’s speech “Ballot or Bullet.”

Such are the makings of an atheist black man who would become today’s preeminent voice on America’s black-white relationship. But between the lines, one can clearly see that Coates never intended to take on this role as our newly elected black atheist leader. As many have noted, liberals have quickly taken to Coates as they credit all their thoughts on race and society to Coates’s articles on The Atlantic. Indeed, Coates told NPR that his thorough investigation of America’s racial past was essentially selfish. He didn’t do it for you, me, black America, or Christian white America—he did it for himself. He saw no comfort in the religious refrain “we shall overcome some day,” and he saw no destined promise land for his race rooted in amazing grace. All he continued to see were examples of the world’s African and Asiatic peoples exploited time and time again by the Christian justifications of a WASP imperialist power structure.

And these justifications (i.e. civilizing, educating the slaves) are born out of the human’s impeccable ability to not only reason out any action one may take but to truly believe in that rationale even in the face of evidence against it. It is a faith that leads to Ta-Nehisi’s powerful refrain about “The Dreamers.” The Dreamers are those who believe in “American Exceptionalism” while ignoring how slavery of the black race solidified the bedrock for the growing mountain that is American prosperity. He writes:

And for so long I have wanted to escape into the Dream, to form my country over my head like a blanket. But this has never been an option because the Dream rests on our backs, the bedding made from our bodies.

This dream, Coates tells his son, will be more than just a dream. Because of the unjust killing of his promising young friend, college student Prince Jones, by a police officer, he tells his son Samori that “they” will never awaken from this permanent slumber and that Samori should never try to wake “them” up, for his struggle is to live his life fully in this doomed world that has consciously and permanently designated him as inferior. The struggle of the young black man, Coates tells him, is to struggle for the memory of one’s ancestors and to struggle for wisdom, family, and community. It is simply to lead a full life as best one can whilst knowing one’s best will never be enough for “them.”

As a black man who is also a humanist, I agree with Ta-Nehisi Coates’s build-up, but I cannot be so quick to praise his conclusion. His doubt that the white majority will ever change and belief that the only prospect for the future black man is the struggle of yesterday and today is something akin to a religious belief in pre-ordained states of being that contradicts his very own disbelief in destiny.

I ask you, Ta-Nehisi, why restrict the possible hopes and aspirations for your son to only the struggle? Is it simply to shield him from the disappointment of his supposedly inevitable failure? To lower his expectations of man to zero so anything above that is a nice, unexpected surprise? None of these are justifications for acting as if you are all-knowing before your son. We do not know what the future holds, and you should not let your atheism strip you or your son of intellectual possibility. We are fundamentally capable of growth and change, as evidenced every day.

If anything, Between the World and Me shows that the slogan “good without a god” is failing to fully express the humanist message to the minority groups of America. Beyond living without god, we also live with something else that is much more crucial: a belief in the infinite importance of every piece of humanity we have above all else. I hope Coates’s lack of hope will wake us up to the difference between atheism and humanism and the possibilities of an applied humanism in our growing racial consciousness.