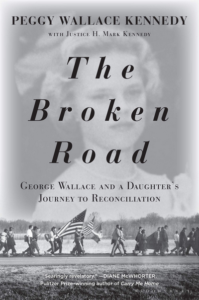

Book Review: The Broken Road: George Wallace and a Daughter’s Journey to Reconciliation

BY PEGGY WALLACE KENNEDY

BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING, DECEMBER 2019

304PP., $28.00

George Wallace, four-term governor of Alabama and three-time presidential candidate, relished hypocrisy. He relished it in himself and in his enemies. And nothing made his political fire-breathing easier than the fact that many Americans liked to imagine that racism and segregation were unique evils in the South when, in obvious truth, they were unique evils all across the country. Whenever a Yankee reporter would challenge him on segregation in Alabama (“I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever!” he shouted at the close of his first inaugural address in 1963), Wallace would, with either a grin that looked like a scowl or a scowl that looked like a grin, point out that things weren’t so different elsewhere. That, for example, in November 1964 almost two-thirds of Californians had de facto voted for segregation in a statewide referendum. And when he would speak in a northern state, he would say he didn’t give a lick whether it was segregated or whether all its people lived in one big commune, brother and sister, black and white, holding hands into the millennium. He would say that with his grin-scowl too—because he knew the dark tunes of American politics and how to play its favorite strings.

The fundamental question of The Broken Road: George Wallace and a Daughter’s Journey to Reconciliation—written by Wallace’s oldest daughter, Peggy Wallace Kennedy—is whether the man was sincere in his racism and segregation or whether these things were just ploys to win elections by riling up the yokels. I understand the imperative a child might have for wanting to know whether their father was really a racist or just a gross opportunist. And, for the common person, I think it’s a fair distinction: the mechanisms for affecting desired consequences are weak, the actual consequences usually small anyway. But for those with power, past a certain point, intentions become academic, which is the polite way of saying irrelevant. I don’t think one Jewish family would sleep sounder at night if it were discovered that Hitler wasn’t really anti-Semitic but was just playing up anti-Semitism for national unity. There would still be the dead. There would still be the consequences.

For decades a revisionist interpretation of Wallace has been in effect. First there was Stephan Lesher’s 1994 biography, George Wallace: American Populist, where Wallace was depicted as a martyr-hero of black integration, falling on the segregationist sword so the South could integrate while keeping its dignity. Wallace, under this interpretation, didn’t thwart black integration, which he literally did at the University of Alabama, but rather sacrificed himself to ease the minds of whites who didn’t want it. “Wallace undoubtedly clarified the inevitability of integration,” Lesher euphemistically wrote, “while psychologically easing the people’s sense of defeat.” Later in life, when Wallace “wanted desperately to become personally respectable,” as Lesher put it, he would say that the only reason he stood in that doorway was to avoid violence: if he hadn’t done it then some Bircher or Ku-Kluxer would have, and they would not have gone as peacefully as he did.

After Lesher’s biography came the 1997 Emmy Award-winning biopic, George Wallace, whose director called his subject a “modern-day tragic hero.” Then came the 2000 PBS documentary George Wallace: Settin’ the Woods on Fire, which portrayed Wallace as a good man corrupted by ambition. (No one, including Kennedy, ever questions whether Wallace’s goodness was just as much a means to an ends as his badness.) When Wallace was a judge, he made sure all black lawyers were treated with respect, and he was (relatively) liberal on race during his first gubernatorial campaign in 1958. “I advocate hatred of no man,” he said in a televised speech, “because hate will only compound the problems facing the South.” He did, however, also say in that speech that he would “continue to maintain segregation in Alabama completely and absolutely.”

Wallace, for the most part, ran a Southern populist campaign that primary. He promised roads, jobs, training, literacy, and more in old-age pensions than all other candidates put together. His main opponent, John Malcolm Patterson, promised a lot of that plus an enthusiastic continuation of the state’s reign of terror over its black citizens. Patterson won by six percentage points, and Wallace swore to learn a thing or two from his defeat. And he did. Four years later, it was him being sworn into office, with Jefferson Davis’s Bible, holding in his other hand a speech written by a KKK pamphleteer.

The revisionist interpretation of Wallace—which Kennedy questions but ultimately embraces—is that Wallace was at heart not a racist but that the ’58 election showed him that if he wanted to be governor—and Wallace had been dreaming about and plotting toward almost nothing else since he was a child—then he would have to pander to prejudice. Why revisionists think this makes Wallace look any better is beyond me. The prejudice he was pandering to wasn’t just in the hearts of white racists. It was in everything. Black Alabamians weren’t humiliated and terrified by mean-spiritedness. They were humiliated and terrified by low wages, the jury who looked the other way when their brothers were murdered, the police who let the Klan know about their sisters throwing a fit about not being allowed to vote, the vitamin deficiencies of their children, the higher interest rates on their loans, the diseases in their ghettos, the wind-rattled walls of their cadaverous homes. That Wallace championed the continuation of such things out of personal ambition rather than ill-will is not the stick of moral dynamite against the consensus fortress that the revisionists think it is.

There is little new personal information about Wallace in Broken Road. Most of the anecdotes Kennedy tells about her father are also in Lesher’s biography and the PBS documentary. That isn’t surprising. As Kennedy knows more intimately than the rest of us, Wallace was a public man: time that could’ve been spent with his family was instead spent slapping backs in hotel bars and shaking hands around town. Everything he did he did to become governor (including staying married for so long to Kennedy’s mother, Lurleen, Wallace’s first of three wives), and after that to becoming president, which might’ve happened eventually if he hadn’t been shot in 1972, which left him paralyzed from the waist down. At that point in the Democratic primary he had already won North Carolina, Tennessee, and Florida (every single county except Miami-Dade), and, the day after the assassination attempt, he won Maryland and Michigan (51 percent in Michigan—some of that sweet, sweet Yankee hypocrisy).

Wallace eventually sought repentance. The man who rode through the sixties shouting “the Confederate flag will fly again!” (and flew that flag over Alabama’s state capitol when JFK’s head of civil rights, Burke Marshall, visited him in Montgomery), the man who was governor on “Bloody Sunday” when civil rights marchers were sprayed with water hoses and bludgeoned by police—that man ended the seventies in the church where Martin Luther King Jr. had been pastor, asking for forgiveness from its black congregation and telling them that he had come to understand their pain. “There was a connection in his mind,” Kennedy writes, “between his journey to redemption through suffering and the African American’s journey to freedom through suffering.”

The revisionists like to make a lot of hay about black America forgiving Wallace. They like to point out that in his last run for governor he got 90 percent of the black vote. But Wallace’s redemption arc suspiciously followed the changing electoral demands of the Democratic Party. As the pastor of King Memorial Church said on the day of Wallace’s funeral in September 1998, “I saw a historical figure…who went with the political flow when it was expedient. And when it was expedient to go the other way, to apologize, to garner support of African Americans, he did that.”

Broken Road is a heartfelt book about a daughter wanting to save her father’s reputation. Kennedy tries hard. When Wallace is bad, she isn’t sure he really means it; when he’s good she’s confident it’s his inner light shining through. When Wallace is bad, she’s sure it was really a subordinate’s fault. (Wallace didn’t write his “segregation forever” speech, he only read it enthusiastically; Wallace only told his racist sheriff to “stop” civil rights protesters, not to crack their heads.) Kennedy doesn’t address some of the more personally ugly accusations against her father. That, for example, Kennedy’s mother requested a closed casket for her funeral, but Wallace, seeing an opportunity for sympathy, opted for an open casket and open ceremony instead. Or that he hid his wife’s cancer diagnosis from her. (In the good ol’ days, the doctor could tell the husband of the patient without telling the patient.)

What’s undeniable is that Wallace would do anything for attention and success. That his revisionists think this is the best defense for him tells just how low a man he was. No one can blame a daughter for wanting to believe her father was a good man, even when everything seems to indicate that he wasn’t. Who knows what was in his heart? Who honestly thinks it matters? As Lady Macbeth discovered, the blood of evil deeds is not so easily washed away by remorse. You must seek forgiveness, not just to be forgiven. Or, as my grandfather used to say, “If you aren’t right, nobody can make you right.”