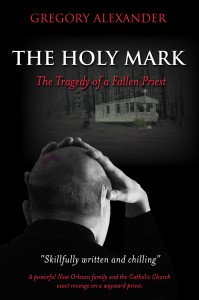

Book Review: The Holy Mark: The Tragedy of a Fallen Priest

The story of the Catholic Church sex abuse scandal has been in the headlines for almost two decades, but few have taken on the challenge of writing about it in fiction. Gregory Alexander’s novel The Holy Mark: The Tragedy of a Fallen Priest is the story of a pedophile priest told by that priest, Father Tony Miggliore, and about how it impacts his career. In the end, the answer is: not as much as someone outside the Catholic Church would hope.

Alexander chooses to narrate the story strictly from the point of view of Father Tony. This choice allows some strengths but also a lot of restrictions, and those restrictions limit the book considerably. Father Tony’s story is one of rationalization, denial, and the firm belief that the pedophilia he engages in is a benefit not only for him but for the vulnerable teenagers he preys on as well. He feels it creates a closer bond between them and will help in his counselling of them. There is no wrestling with this belief in the soul of Father Tony. What comes through is a chilling, straightforward account of Father Tony’s experiences and his skewed view of how it is all right.

What doesn’t come through is any sense as to why someone would come to feel this way, other than a vague sense that he was harshly treated by his extended family as a child as a result of his mother’s inheritance. But even this insight becomes suspect as you are made to see things through the eyes of Father Tony, and in his eyes, anyone who doesn’t think he’s a wonderful person harbors some sort of jealousy towards him that propels them to try and thwart his plans and desires. This includes the archbishop, a crony of his uncle, who keeps shifting Father Tony around as knowledge of his proclivities grow. Father Tony sees the archbishop only as a hindrance and an enemy, while the reader just thinks that the archbishop’s benign cover-ups and resulting transfers of Father Tony couldn’t really have happened (except we know now that they routinely did—an instance in which truth is stranger than fiction).

What the archbishop was thinking and doing during all this covering up would have been an interesting story: the interplay of knowing Tony and his family from the time he was a young boy, the interplay of the family struggles and the archbishop’s association with them, the need to protect the public dignity of the church, and the revulsion he hopefully felt upon realizing Father Tony’s actions. But none of this is explored, except through the limited prism of Father Tony who sees it all as a vindictive jealousy on the part of his uncle and the archbishop.

For a novel about a priest, God plays almost no role in the book at all, other than fleeting thoughts by Father Tony that God fully understands and supports his “work.” One thing that is obvious is that Father Tony’s belief in God gives him no pause in his pedophilia.

The narration of Father Tony is also peppered with many asides and digressions about Catholicism brought on almost through word association. While some of these are interesting in themselves, most do little or nothing to actually move the story line along. Father Tony himself comes off as self-indulgent, self-centered, and all in all, not very sympathetic.

If you’re looking for insight into the disturbed thinking of a pedophile priest, this novel may provide that, and it does a good job of letting that speak for itself in how horrendously mundane that thinking can be. But if you’re looking for an exploration of the contradictions such a pattern of behavior might cause in the mind of someone who is supposedly dedicated to the betterment of his fellow man, this isn’t it.