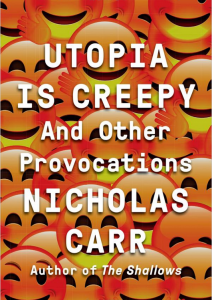

Book Review: Utopia is Creepy

BOOK BY NICHOLAS CARR

Nicholas Carr’s Utopia is Creepy: and Other Provocations has so many great zingers in it that it’s a shame one can’t simply pull a thousand words’ worth of quotes from the book and count that as its review.

On the other hand, the book is more than just eminently quotable. It’s also significant for the questions it raises about our relationship with technology. Such as, how is the Internet affecting our endurance for focusing? What talks should be done by machines and who should decide? Can personal technology seduce us away from things we find pleasurable or fulfilling? Can we have the peace and prosperity technological enthusiasts promise without an accompanying lifelessness? Grappling with such questions, technology and culture writer Carr offers sound ideas condensed into impressive aphorisms and old epigrams fitted for new purposes. He isn’t shy about recommending solutions either.

“Ours may be a time of material comfort and technological wonder,” says Carr, “but it’s also a time of aimlessness and gloom.” Technology is making our lives easier but less fulfilling. With physical work that would otherwise keep us fit delegated to automatons, and mental labor beginning to be pushed down a similar path, we either seek desperately to escape our inertia through artificial replacements or we’re unaware that it even exists.

We used to escape unpleasant facts through religion, work, or overindulgence. Now, with the advent of the Internet and its ever-growing omnipresence, Carr believes “social networking” can be added to that list: “The great paradox of ‘social networking’ is that it uses narcissism as the glue for ‘community.’ Being online means being alone, and being in an online community means being alone together.” Whereas new technologies have always arrived to replace old modes of production, Carr finds this particular stage of the Internet so pernicious because it also appears to be replacing old modes of being. He cites academic studies that allege we’re losing our capacities for memorization, patience, and self-clarification, while those same studies report that confidence in our own mental abilities has never been higher. “The Internet may be making us shallow,” Carr writes, “but it’s making us think we’re deep.”

Social media is replacing our longing for a sense of community with facades of socializing. Only 3 percent of time spent on social media sites is actually spent interacting with others according to another study Carr cites. The rest is spent “browsing,” “lurking,” or “stalking.” The interface vernacular of these communication websites, however, partly obscures the fact that very little communicating actually takes place. “The illusion of involvement,” as Carr puts it, “conceals its absence.”

Utopia is Creepy also addresses the economy of social media sites, which he likens to a “modern kind of sharecropping system.” Internet businesses such as Facebook, Twitter, and Yelp create spaces for their members to produce online content, then monopolize the economic value of that content. To Carr, blame lies not in any particular company’s business model but in the current structure of the Internet, where wealth tends to accelerate toward those with the biggest servers. As the tenant farmer gives his produce to the landowner because that’s who owns the land, users give their opinions, thoughts, and rankings to these businesses because they’re who own the digital pathways. We become, in Carr’s striking expression, “bureaucrats of experience” for these companies.

It used to be that leaving the home meant disconnecting from the Internet for a time. But with the technological developments in smartphones, the digital world can now be brought with us anywhere—and, when it comes to Silicon Valley services, anywhere tends to translate equally well to everywhere. For Carr, just as the demarcation between work and fulfillment is becoming bolder, the demarcation between online and offline is becoming lighter, and he sees the smartphone as largely responsible. “Every new smartphone should have affixed on its screen one of those transparent, peel-off stickers bearing the following warning: ‘Abandon hope, ye who enter here’”—a clever (and perhaps pertinent) allusion to Dante’s inscription over hell’s gates.

The smartphone-obsessed are of course easy to mock. Those who record a concert rather than enjoy it or who stare listlessly at a screen during dinner rather than contribute to the conversation deserve contempt, even if Facebook tries to spin their acts of servitude as acts of rebellion. (“It may look like thumbs on a screen, but in truth it’s a middle finger raised straight in the face of power,” ran one technology writer’s commentary on a Facebook advertisement that depicted a teenage girl fiddling on her phone while seated at the family dining table.)

For the most part, Carr derides neither the smartphone-afflicted nor the abusers of any other digital product or service. Rather, his scorn is appropriately reserved for the politicians and tech barons. Politicians have shrunken their messages in accordance with the new mediums. For instance, Carr likens recent electoral campaigns on Twitter to the old populist carnival circuits in the 1920s—where the loudest, silliest, most guilt-expunging voice would often win the crowd’s favor. As for the tech barons, Carr merely quotes their own words to show how, for all their ingenuity and imagination, inane and subliterate most of them unsurprisingly are.

To many, Utopia is Creepy will read like nothing more than the doom-haunted prophecies that every generation, from Swift’s to Huxley’s, tells itself, especially when technological changes are closely linked with deeply-felt cultural ones. There have always been Luddites and technology skeptics, going as far back as Ancient Greece. As proof Carr mentions an amusing scene from Plato’s Phaedrus in which Socrates denounces the potentially deleterious effects of writing as it might discourage the practice of memorizing.

That your predecessors got it wrong doesn’t necessarily mean you have, however. To purge all suffering shouldn’t require one to purge all of what makes life worth living. But that’s Carr’s biggest fear, along with the idea that those who will be most affected by the digital revolution will have no say in its course. Or even that those who claim to be guiding it have far less control over it than they claim. That instead we’re stuck on automatic—and have been all along.