Human, Not Object: Feminist and Humanist Messages in Jessica Valenti’s Sex Object

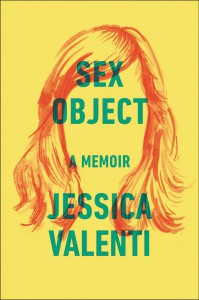

In the introduction to her latest book, Sex Object, feminist activist and 2014 recipient of the American Humanist Association’s Humanist Heroine award Jessica Valenti acknowledges that the title is controversial. The book is a memoir about Valenti’s experience growing up female under the unrelenting gaze of patriarchal culture, from her preteen encounters with flashers on the New York City subway to her dating run-ins with men who harassed and misled her. Valenti applies the term “sex object” to her life with a heavy dose of irony, informing her readers that the term is used with “resignation” rather than “reclamation.”

“I have girded myself for the inevitable response about my being too unattractive to warrant this label, but those who will say so don’t realize that being called a thing, rather than a person, is not a compliment,” Valenti writes in the introduction. Sex Object subverts the cultural paradigm that tells women that their worth is primarily dependent on their ability to appear attractive to heterosexual men. In boldly telling the story of her life through the lens of the belittling, disrespectful, and even traumatic experience of being sexually objectified, Valenti insists upon her own humanity and dignity. This powerful message informs the central theme of her memoir, and it’s a theme that will resonate with many feminists and humanists.

Feminists have discussed the concept of “the male gaze,” a term first coined by feminist film critic Laura Mulvey to describe the ways women in film and art are depicted—not as autonomous human beings but as objects of heterosexual men’s desires. Since Mulvey’s groundbreaking essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” first introduced the concept of the male gaze, many feminist theorists have noted that this objectifying view of women also exists outside of art and film in the day to day dealings that women have with men.

In Sex Object, Valenti chronicles her own personal interactions with the male gaze and how it damaged her confidence and her sense of self. While the daily barrage of catcalls and groping she suffered on the subway as a young girl may seem to be a natural part of growing up, Valenti reveals just how draining and ultimately painful these instances are. For example, after having a man expose himself to her on an empty subway platform while she was on her way to junior high, Valenti describes a sense of panic: “I knew I was supposed to yell or run, but I just stood there…even though I felt my knees giving out, my feet felt strongly planted to the ground…I noticed that my hands and face had pins and needles from my breathing strangely.” This encounter is just one of many that Valenti endured as an adolescent accosted by adult men, and she succinctly describes the impact that these experience had on her young psyche, as well as on the minds of other girls who suffer them: “we are here for [men’s] enjoyment and little else.”

Though Valenti never explicitly states how these early interactions with men influenced her later choice of boyfriends, many of whom insult, harass, and even abuse her, the narrative of her memoir leads the reader to understand that in a climate of near constant objectification, Valenti, like countless other women, came to see herself in some ways as less important, less worthy of respect, and even less human than the men in her life. “Somewhere along the way,” she explains, “I started to care more about what men thought of me than my own health and happiness because doing so was just easier.” And after spending so much of her formative years being implicitly told that she was a sex object meant to please men, how can the reader blame Valenti for taking this attitude toward romantic relationships? When a woman is treated, repeatedly, as though her own needs and desires don’t matter compared to those of the men in her life, she will likely start to believe it.

In bravely telling her story, however, Valenti refuses to let the male gaze ultimately define her. In the very act of recounting her own life, she asserts that her needs, her desires, and her perspective all have value. While she does not reclaim the term “sex object,” she does reclaim her own subjectivity and the right to define her own identity and worth on her own terms. She admits that sometimes this effort feels like faking it, so much so that she dedicates an entire chapter, appropriately named “Fakers,” to the work required to appear confident and self-assured, in spite of a wider culture that seems dedicated to tearing her down and muting her call for women’s equality. The American Humanist Association even gets a reference in this chapter:

On my thirty-sixth birthday my daughter presented me with a “book” she had written because she wants to be a writer, like me, she said. The book, written on construction paper in crayon, bound together by string, was about watching me give a speech. I was accepting an award from a humanist organization, and Layla sat in the front row, avoiding her salmon but excited about the chocolate cake with raspberry ganache, looking at me. She watched me talk for a while and didn’t say much but wrote this book and drew the award, a placeholder for my confidence with my name etched in glass, proving I’m actually here.

A lifetime of sexual objectification may be impossible to overcome completely if even Jessica Valenti, one of the most accomplished and successful feminist activists and writers of our time, can still feel like a “faker” after all she has done to empower a generation of feminists to continue the fight for women’s rights. That Valenti is still grappling with the emotional consequences of the sexism directed at her is not, however, an admission of defeat. Rather, she identifies a certain power in recognizing, naming, and condemning the cultural and social systems that oppress women and express themselves in the interactions between women and men. “Some women heal by rejecting victimhood,” Valenti acknowledges, “but in a world that regularly tells women they’re asking for it, I don’t know that laying claim to ‘victim’ is such a terrible idea. Recognizing suffering is not giving up and it’s not weak.”

Ultimately, Valenti takes a generational approach to solving the problem of sexual objectification that women face. She traces the trauma of being a sex object from her grandmother, who was raped, to her mother, who was molested by a relative, to her own experiences with abusive and careless boyfriends. She notes that while the sexual objectification of women in her family has continued, it has become diluted. She also earnestly expresses her desire to see her daughter grow up in a world in which she will not have to be afraid or undergo the same objectification and abuse that she has experienced. Just as sexism is taught, both within the dynamics of the home and in the wider culture, so too can feminism and women’s liberation be taught and passed down to the next generation. Valenti is making the world a safer, more empowering place for the next generation of feminists to continue championing women’s rights.