Something Good to Read: Highly Recommended Humanist Books

Photo by Kate Williams on Unsplash

Photo by Kate Williams on Unsplash As the days roll on amidst the COVID-19 pandemic and we curtail most social interactions, we’re all finding creative outlets to remain physically and mentally healthy and engaged. Some people are picking up projects they couldn’t find the time to finish before, while others are seeking solace in a walk around the block. I’m finally getting to that stack of books on my nightstand, and I’ve rediscovered a sweater I started knitting months ago. However, if you’re without a laundry list of “to-do crafts and books,” or maybe you’ve already plowed through the ones you have, the American Humanist Association’s Center for Education has some great recommendations.

I asked colleagues and adjunct faculty members of the Humanist Studies Program to share our current favorite humanism-oriented books.

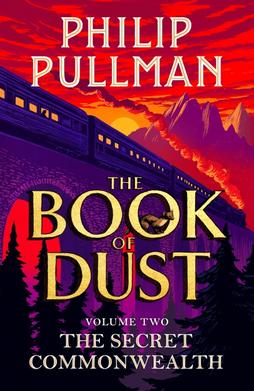

Recently retired New York Society for Ethical Culture Leader Anne Klaeysen suggests a must-read in humanist author Philip Pullman’ trilogy, The Book of Dust (a return to the world of his first trilogy, His Dark Materials). Having just finished the second book in the newer set (The Secret of Commonwealth), Klaeysen is considering rereading the first trilogy as she awaits the next installment.

Recently retired New York Society for Ethical Culture Leader Anne Klaeysen suggests a must-read in humanist author Philip Pullman’ trilogy, The Book of Dust (a return to the world of his first trilogy, His Dark Materials). Having just finished the second book in the newer set (The Secret of Commonwealth), Klaeysen is considering rereading the first trilogy as she awaits the next installment.

Ellen Morton, in her Washington Post review of The Secret of Commonwealth, writes:

At over six hundred pages, the story is neither brief nor straight to the point, but it’s well worth sinking into. It is perhaps the most overtly philosophical addition to a body of work already brimming with big ideas…. Pullman closes this story at an inflection point that feels organic to the action but also leaves the reader in a state of almost hysterical suspense.

Christopher Driscoll, assistant professor of Religion Studies, American Studies, and Africana Studies at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania, highly recommends the following three books:

The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter (1940), Carson McCullers’s debut novel. The National Endowment for the Arts overview of the book notes it’s “hard to believe that The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter was the first book of a twenty-three-year-old author (who had started the novel at nineteen!). This tragic, small-town drama is so ambitious in its scope—presenting five radically different characters whose troubled lives intersect in the Depression-era South—it always seems like the work of a master storyteller.”

Killers of the Dream is about Lillian Smith’s memories of childhood depicting the costs and contradictions about sin, sex, and segregation in Southern society. W.W. Norton & Company notes the 1949 book was “published to wide controversy, it became the source (acknowledged or unacknowledged) of much of our thinking about race relations and was for many a catalyst for the civil rights movement. It remains the most courageous, insightful, and eloquent critique of the pre-1960s South.”

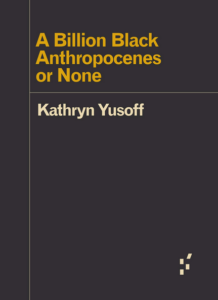

Driscoll’s third pick is the 2018 book A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None by Kathryn Yusoff. Chantelle Gray, in her review on NewFrame.com, notes that Yusoff “locates the origins of climate change in slavery while exploring the grammars of capture, extraction and displacement.” She says the book

Driscoll’s third pick is the 2018 book A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None by Kathryn Yusoff. Chantelle Gray, in her review on NewFrame.com, notes that Yusoff “locates the origins of climate change in slavery while exploring the grammars of capture, extraction and displacement.” She says the book

could be summed up as a new history of the relationship between geology and subjectivity. This is by no means a novel concern—pre-black conscious writers such as W. E. B. du Bois, black conscious writers including Frantz Fanon and Steve Biko, and their contemporaries and successors, for example Sylvia Wynter, Achille Mbembe and Katherine McKittrick, have all grappled with the complex human-citizenship-land question.

However, Gray notes that what sets Yusoff’s book apart “is that it addresses these questions via contemporary concerns about the Anthropocene, the name given to the new geological epoch. Unlike previous epochs, such as the Pleistocene, which was marked by climatological planetary impacts—in this case repeated glaciations, which is why it’s also called the Ice Age—the Anthropocene is marked by human interference.”

From the bookshelves of the First Unitarian Society of Minneapolis, Senior Minister David Breeden shares his most recent best read: Gods of the Upper Air: How a Circle of Renegade Anthropologists Reinvented Race, Sex, and Gender in the Twentieth Century (2019) by Charles King.

King presents the history of cultural anthropology featuring the scientists who pioneered its discovery and the birth of our multicultural world. Reviewing Gods of the Upper Air in the Atlantic, Alison Gopnik writes:

Charles King, a professor of international affairs and government at Georgetown, makes the case for anthropology in a thoughtful, deeply intelligent, and immensely readable and entertaining way. The book is a joint biography of people who created anthropology, at the turn of the last century: Franz Boas, the father of the field, and the women who were among his first influential students, especially Ruth Benedict, Zora Neale Hurston, and Margaret Mead.

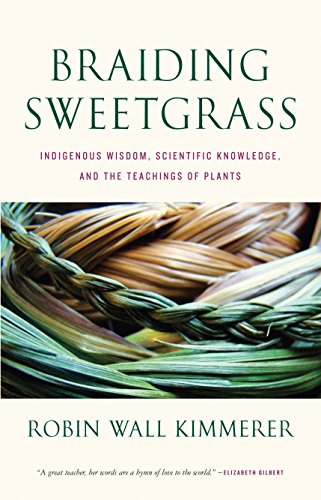

Sharon Welch, senior fellow of the Institute for Humanist Studies and professor of religion and society at Meadville Lombard Theological School, recommends from her library two additional choices: Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants (2013) by Robin Wall Kimmerer and The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative (2008) by Thomas King.

Sharon Welch, senior fellow of the Institute for Humanist Studies and professor of religion and society at Meadville Lombard Theological School, recommends from her library two additional choices: Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants (2013) by Robin Wall Kimmerer and The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative (2008) by Thomas King.

Braiding Sweetgrass offers a look at how other living things provide gifts and lessons. Wall Kimmerer, a trained botanist and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, highlights the concept that plants and animals are our oldest teachers. She argues that understanding “ecological consciousness” requires knowing and observing our interdependent relationship with the world. Elizabeth Wilkinson of the Star Tribune in says,

The gift of Kimmerer’s books is that she provides readers the ability to see a very common world in uncommon ways, or, rather in ways that have been commonly held but have recently been largely discarded. She puts forth the notion that we ought to be interacting in such a way that the land should be thankful for the people.

In The Truth About Stories, King examines not only how stories shape who we are but how we understand and relate to others. Suzanne Methot, writing at Quill and Quire, notes that King:

uses snatches of memoir, quotations from settler histories, American literature, new native literature, stories from the aboriginal oral tradition, and exposition to discuss everything from racism and capitalism to aboriginal identity and the relationship between aboriginal people and colonial governments in both the US and Canada. These points are interesting enough in themselves, and the book could be read simply at that level.

“The Truth About Stories is a wonderful book,” she elaborates. “It leaves us with the hope that if we create better stories—and stop believing dangerous stories—we can create a better world. Because the truth about stories is that we get the world we imagine, and in that sense, we get the world we deserve.”

“The Truth About Stories is a wonderful book,” she elaborates. “It leaves us with the hope that if we create better stories—and stop believing dangerous stories—we can create a better world. Because the truth about stories is that we get the world we imagine, and in that sense, we get the world we deserve.”

Last, I leave you with a book that came recommended to me by a longtime colleague and friend, Robert Tapp, who noted the book “should be celebrated.” How to Live the Good Life: A Guide to Choosing Your Personal Philosophy will certainly make my bedside stack a little higher. Edited by Massimo Pigliucci, Skye C. Cleary, and Daniel A. Kaufman, the book is a collection of fifteen philosophical essays on how to live an “examined and meaningful life”—from Daoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism to Aristotelianism and Stoicism, to the four major religions, as well as existentialism and effective altruism.

Happy reading!