Staff Picks: Our Favorite Banned & Challenged Books

This week kicks off Banned Books Week, an annual celebration of the freedom to read that calls attention to books that are frequently challenged or sometimes outright banned.

To support this effort, staff at TheHumanist.com have picked their favorite banned or challenged books below.

|

|

|

|

Maggie Ardiente, Senior Editor, TheHumanist.comOf Mice and Men by John SteinbeckJohn Steinbeck’s gritty portrayal of two migrant workers during the Great Depression makes Of Mice and Men one of the most moving books I’ve ever read (another Steinbeck novel, Cannery Row, is my all-time favorite). I remember, rather embarrassingly, weeping loudly in my tenth-grade English class during the scene when Lennie first complains to George about wanting his beans with ketchup, then, upon seeing George’s anger, says, “I don’t want no ketchup. I wouldn’t eat no ketchup if it was right here beside me…I’d leave it all for you. You could cover your beans with it and I wouldn’t touch none of it.” This book is a gem, which is why I’m shocked that Of Mice and Men is ranked in the top ten of the most banned books in the United States. Even as recently as May of this year, parents in Idaho tried to get the book banned due to “profanities” such as “bastard” and “God damn.” As if high school students weren’t already using this language! |

|

|

|

|

Jennifer Bardi, Senior Editor, TheHumanist.comSlaughterhouse-Five by Kurt VonnegutSlaughterhouse-Five is a wildly inventive commentary on the horrors of war that only the genius and humanism of Kurt Vonnegut could produce. The book has been banned and challenged in many states over the years, mainly for profanity, sexual content, and depictions of violence. But I laughed out loud when I learned that it was challenged in 1985 at the Owensboro High School library in Kentucky for, in part, “reference to ‘Magic Fingers’ attached to the protagonist’s bed to help him sleep, and the sentence: ‘The gun made a ripping sound like the opening of the fly of God Almighty.”‘ Interestingly, it was banned in schools in Rochester, Michigan, in the early 1970s because it contained and made reference to religious matters and, argued whoever brought the suit, fell within the ban of the establishment clause. An appellate court upheld its usage there in 1972. |

|

|

|

|

Peter Bjork, Managing Editor, TheHumanist.comThe Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret AtwoodI can still remember the vivid feeling of horror and fascination that came over me when I realized exactly what was going on in Margaret Atwood’s classic dystopian novel The Handmaid’s Tale. This bewildering book tells the story of a woman living in a future United States under a totalitarian Christian theocracy. Even as the ideas in Atwood’s book creep closer and closer to a horrifying reality, Handmaid’s Tale is often challenged for inclusion in school curriculums—sometimes for the bogus reasons of “defaming God” and encouraging “bullying of Christian students.” It’s a fantastic piece of literature. I only hope Atwood’s believable fictional world doesn’t become reality. |

|

|

|

|

Fred Edwords, Director of Planned GivingLysistrata by AristophanesWhen it comes to banned literature, one of the world’s earliest is the play Lysistrata by Aristophanes. Soon after it opened in Athens in 411 BCE its continued performance was declared subversive by the authorities. Why? First because it is an anti-war comedy in which the women of Athens and other city states go on a sex strike to stop the fighting against Sparta and its allies. Only a year earlier, thousands of Athenian soldiers had died in that conflict in a Sicilian military disaster–one no less traumatic than the United States’ defeat in Vietnam. Second, because the play features what Blake Morrison of the Guardian calls “a coarseness of language unrivalled in the ancient world.” And third, because the play, while making fun of every character and cause it takes up, has been an inspiration to feminism. In book form, Lysistrata was banned at various times and places–or honest and complete translations were forced underground. One particularly famous example of the latter is the 1896 translation of Samuel Smith, published in England by Leonard Smithers, the pornographer to the elite, with famously explicit illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley. (A starting bid at Christie’s on an original copy from this limited edition is $7,730 US. But you can settle for the modern paperback reprint at Amazon for $12.31 or download for free at Project Gutenberg the also-famous 1925 version translated by Jack Lindsay and illustrated by Norman Lindsay.) In the United States Lysistrata in any form was banned in 1873 by Anthony Comstock and, under the Comstock laws, that ban wasn’t lifted until the 1930s. It’s good to be out of those woods. |

|

|

|

|

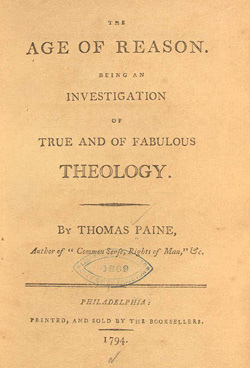

Luis Granados, Director, Humanist PressThe Age of Reason by Thomas PaineThe Age of Reason, by Thomas Paine, is by my lights the most profound statement on religion the world has yet seen. Paine believed in “God,” but not in religion:

Naturally, it was banned. In Britain, the same lawyer who had defended Paine’s previous political work switched sides and led the (successful) prosecution of a seller of the book, whose publisher spent over nine years in prison. Paine himself never recovered from the hatred of the God experts, one of whom predicted that, “Like Judas, he will be remembered by posterity; men will learn to express all that is base, malignant, treacherously unnatural, and blasphemous by the single monosyllable of ‘Paine.’” Even Paine’s bones were stolen from his grave by vicious Christians. What better advertisement could there be for a book? |

|

|

|

|

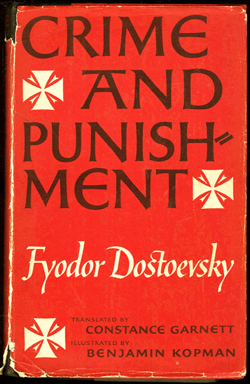

Meghan Hamilton, Development and Social Media AssistantCrime and Punishment by Fyodor DostoyevskyCrime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky is one of my favorite novels of all time and is one that often finds its way onto banned books lists, often because of the book’s dark nature. It poses moral dilemmas and can be psychologically disturbing at times. Regardless, it is a beautifully written book and every time I start it I can’t put it down. |

|

|

|

|

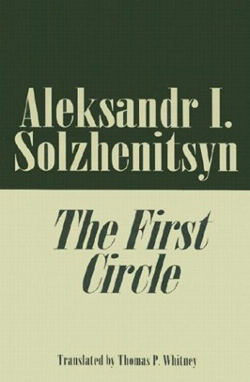

Jan Melchior, Graphic DesignerThe First Circle by Aleksandr SolzhenitsynThe First Circle by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn is one of my favorite books of all time. I read it about 100 years ago in high school, but I have referred back to certain passages through the years for inspiration. One follows:

After Nikita Khrushchev was removed from power in 1964, all current and future works by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn were banned in the Soviet Union. |

|

|

|

|

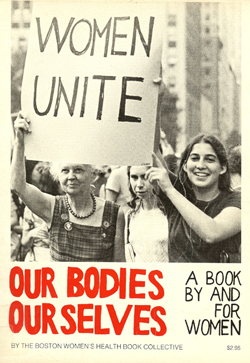

Merrill Miller, Communications AssociateOur Bodies, Ourselves by the Boston Women’s Healthbook CollectiveWhen it was first published in the 1970s, it was revolutionary in its honest approach to women’s health and sexuality. It represents not only the strides that the feminist movement made toward sexual liberation but also the importance of women working together as a collective to challenge societal taboos. It remains a touchstone of the women’s movement that played a role in inspiring the frank conversations happening today regarding rape, sexual assault on college campuses, and the continuing fight for reproductive justice. |

|

|

|

|

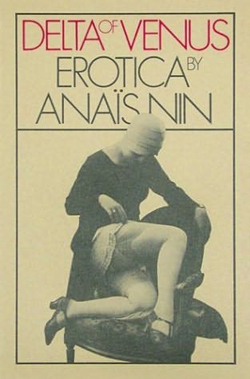

Jessica Xiao, Projects AssistantDelta of Venus by Anais NinMy words in praise of this collection of erotica written for a client known as the “Collector” (who also commissioned works from author Henry Miller and poet George Barker) pale in comparison to Nin’s own words about its cultural significance (and sexiness):

|