Hope Is What Remains Rush drummer and lyricist Neil Peart has long explored humanistic themes

Drummer Neil Peart performing with Rush in 2012 (photo by Clalansignh via WikiCommons)

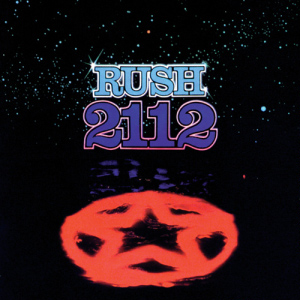

Drummer Neil Peart performing with Rush in 2012 (photo by Clalansignh via WikiCommons) April marks the fortieth anniversary of the release of Rush’s album 2112, described by Rolling Stone as the band’s “prog-rock magnum opus” and by Rush guitarist Alex Lifeson as their “protest album.”

It was reported earlier this year that Neil Peart, drummer for the Canadian rock trio, Rush, would retire from touring after four decades with the band, citing chronic tendonitis as the reason he was, to borrow his words, taking himself out of the game. (The band has left open the possibility that they’ll record more music in the future.) This is actually the second time Peart has left the stage, the first being in the late 1990s when his daughter died in a car accident and his wife died ten months later of cancer. But after four decades as the lyrical heart and rhythmic foundation of an iconic band, perhaps this time is really the end of an era.

The inescapable reality of our lives is that these machines—organs and connective tissue and bones—are destined to wear out. If our bodies are designed, let us note, the designer offers a short warranty and a planned obsolescence. But acknowledging the realities only underscores the loss we feel when those who have spent years expanding human culture must step back from daily continuation of this work. One song, “Losing It,” from Rush’s 1982 album Signals must have been particularly poignant when performed on the band’s fortieth anniversary tour last year, considering that its theme is the end of careers in the arts, explored in the examples of an aging dancer and writer and evoked by Peart’s quotation of John Donne, “the bell tolls for thee.”

The technical prowess of Peart as a musician is a matter for experts in that field to discuss. My own game is language, and so I wish to speak of the words Peart has given us since 1975. Of particular interest is his consistent theme of humanism in his song lyrics, and by humanism I don’t simply mean a denial of whatever gods have been worshipped over the millennia, but the celebration of human beings in all our complexity and potential, and a reaction to what many feel ought to be a just universe, but isn’t. And it is this celebration and also defense of human worth and potential that is the basis, the guiding spirit, of so much of Peart’s writings. And yes, he issues a continual indictment of any gods that could preside over the injustices of life.

Much has been written about Peart’s Objectivist leanings in the beginning days of his career. In a March 29, 2016, Rolling Stone interview, Alex Lifeson reflected on his reaction to Peart’s Ayn Rand-inspired lyrics for 2112: “What appealed to us was what she wrote about the individual and the freedom to work the way you want to work, not the cold, libertarian perspective. For us, it was striving to be a stronger individual more than anything, and that’s how the story came together.” Whatever may have been Peart’s inspiration, the album offers an essential statement of individual humanism.

The album 2112 presents the story of a man in a future dystopian society that controls all forms of music and, by implication, all creative expression. He discovers an antique guitar and after learning to play it—without a guide to show him, importantly—attempts to introduce music that each person can play individually back into his world. What follows is ambiguous, but at least one reading of the lyrics is that his actions spark a revolution or the intervention of beings called the elder race to restore freedom. This may feel like a need for intervention from outside, but at least what starts things off is one person’s choice.

The album 2112 presents the story of a man in a future dystopian society that controls all forms of music and, by implication, all creative expression. He discovers an antique guitar and after learning to play it—without a guide to show him, importantly—attempts to introduce music that each person can play individually back into his world. What follows is ambiguous, but at least one reading of the lyrics is that his actions spark a revolution or the intervention of beings called the elder race to restore freedom. This may feel like a need for intervention from outside, but at least what starts things off is one person’s choice.

Is this humanism? It has obvious links to Rand’s 1938 novella, Anthem, and the album is dedicated to her genius. Curiously, it also has much in common with C. S. Lewis’s narrative poem, Dymer, written during his period of atheism in the early 1920s. I am not aware of Peart ever having read that work, but the disaffected rebel striking out against a conformist world is the fantasy of many young adults. But pressure to identify with the group—whether this is the church or the state—is itself a denial of individual human worth. Standing up to that may look like youthful exuberance, but it is also a defense of the dignity and rights of each of us. (It’s worth noting that the album itself was an act of individualism, since the band’s record label had told them to produce a more commercially friendly work with the implication that this was their last chance.)

Over the course of Peart’s writing career, at least two lines of humanist expression are to be found in his lyrics. First is a challenge to the belief that everything is the product of design, with the corollary that meaning must come from some outside source. Take, for example, the title track of Rush’s 1991 album Roll the Bones:

Why are we here? Because we’re here.

Roll the bones, roll the bones.

Why does it happen? Because it happens.

Roll the bones, roll the bones.

The bones in this case refer to dice, a statement that our existence is the product of chance, rather than planning. Peart, who in so many songs shows himself to have a deep feeling for the sorrows of human suffering, insists here that if design shapes reality, as Robert Frost once wrote, what could that be but a design of darkness to appall? The second verse of the song describes children being born into starvation and disease and then asks what kind of deity would allow this outcome.

Peart continues this ethical challenge to a designer of the world in “The Larger Bowl,” from 2007’s Snakes and Arrows:

Somethings can never be changed.

Some reasons will never come clear.

It’s somehow so badly arranged

If we’re so much the same like I always hear.

This is a key objection that religions have difficulty answering—the effort is referred to as theodicy, the attempt to justify the acts of a deity—and it would be trite to keep pointing it out if we were not told repeatedly about how we are “fearfully and wonderfully made,” as the psalmist said however long ago.

Peart’s strongest challenge of design comes in what could be the band’s last studio work, Clockwork Angels (recorded in 2012). This concept album retells the story of Candide as that of a young man who lives in a world shaped by a watchmaker (alluding to William Paley’s argument) who has planned out every detail, as laid out in the song, “BU2B” (Brought Up to Believe):

In a world of cut and thrust,

I was always taught to trust.

In a world where all must fail,

Heaven’s justice will prevail.

The joy and pain that we receive

Each comes with its own cost.

The price of what we’re winning

Is the same as what we’ve lost.

The reality the young man lives in is the antithesis of humanism, one reminiscent of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. The answer to every question is that things are as they must be—the answer that in fact answers nothing and insists on silencing inquiry. This answer also hands over responsibility for the moral quality of our actions. Peart lays out a summation of the anti-humanist position in the same song:

Believe in what we’re told

Until our final breath,

While our loving Watchmaker

Loves us all to death.

Until our final breath,

The joy and pain that we receive

Must be what we deserve,

I was brought up to believe.

Peart presents both the core of the design argument and its key flaws in terms of morality. There are good scientific reasons for denying design, but there are also good humanistic reasons that Peart chooses to use—namely, the repeated observation that if the universe is organized according to a plan, the planner is either incompetent or immoral. The indictment he makes is against the claim that the universe has a moral quality that in any way is not the result of human action.

And this brings us to Peart’s other major theme, the challenge of finding meaning—or to put that a better way, of creating meaning, since the essential humanist claim is that what we make with the labor of our own hands and minds is worthy in reference to ourselves, if for no other reason. If we are to make a moral world on the basis of our good sense, we have to value the lives of ourselves and of others.

An audience favorite that shows this second line of humanism in Peart’s lyrics is the song, “Free Will,” from the 1980 Rush album, Permanent Waves. This song features an instrumental trio that is itself an expression of human potential, but the words articulate the humanist response to a universe that is either malevolent or simply doesn’t care:

You can choose a ready guide

In some celestial voice.

If you choose not to decide,

You still have made a choice.

You can choose from phantom fears

And kindness that can kill.

I will choose a path that’s clear.

I will choose free will.

The building of meaning for ourselves is based on this assertion. If we don’t decide, we’re left with whatever we are presented, thereby leaving us with no good cause to complain and really no moral quality to our lives. The risk of choice has to be accepted to gain the rewards, to create the meaning Peart explores throughout his writing.

For Peart, one key answer to the problem of creating meaning is love. In this, he echoes Matthew Arnold’s 1867 poem, “Dover Beach.” Recall that the speaker of that poem feels empty when considering the withdrawal of what he calls the “Sea of Faith” and seeks to replace the lost certainties by connection with a woman who is with him.

One example of Peart’s assertion of love is in “Ghost of a Chance,” from Roll the Bones. As discussed, the overall theme of the album is how we deal with chance, and this particular song accepts the reality that destiny is nonsense—that the concept of a “soul mate,” whether planned for us by a deity or not, has no factual basis:

I don’t believe in destiny

Or the guiding hand of fate.

I don’t believe in forever

Or love as a mystical state.

I don’t believe in the stars or the planets

Or Angels watching from above,

But I believe there’s a ghost of a chance

We can find someone to love and make it last.

This sounds a bit like the theory of evolution by natural selection. Mutations are by chance, while how those mutations succeed or fail in the environment is based on how well they’re suited for that environment. But the better analogy with love is artificial selection. Just as mutations are random, so are the encounters we have with other people, at least within the deterministic boundaries of geography. And, contrary to a lot of romantic notions, there are likely many people out there in the world with whom we could get along very well, but we only meet some of them in the course of our lives. But as Peart insists, we choose through our free will to make a relationship work—“We can find someone to love and make it last.” Destiny need not apply; it is human choice and human action that matters.

This theme continues in the song, “Faithless,” from Snakes and Arrows. The humanist perspective and atheism as well get attacked as lacking in a sense of awe, of wonder, of beauty, as if this approach to life may be correct, but is without joy—without the vaguer word, soul. Christopher Hitchens loved to cite images from the Hubble telescope as an example of awe in naturalistic terms. Peart addresses this with a declaration of what he finds inspiring:

I don’t have faith in faith.

I don’t believe in belief.

You can call me faithless.

I still cling to hope,

And I believe in love.

And that’s faith enough for me.

This is the insistence that how we relate to each other is the core meaning of human life, not some externally provided purpose. Does he mean “faith” as it is usually meant? Perhaps, especially if we take the common sense meaning of the word as a choice to believe in the absence of evidence. A better way to put that would be to say that we decide what our assessment or determination of the quality of the world will be by our actions.

The idea of finding our own purpose is something Peart also addressed in the earlier-quoted song, “Roll the Bones.” In a reality that presents the results of chance, not design, the burden is on each one of us to make the best use we can of what we’re handed:

What’s the deal, spin the wheel.

If the dice are hot, take a shot.

Play your cards, show us what you got,

What you’re holding.

If the cards are cold,

Don’t go folding.

Lady Luck is golden.

She favors the bold, that’s cold.

Stop throwing stones,

The night has a thousand saxophones,

So get out there and rock

And roll the bones.

Get busy.

The accusation often leveled by fundamentalist believers in various religions is that a life without deities has no worth, and Peart answers this directly. Worth is what we make it, and it’s our job to engage in the making. Peart draws his humanist themes together in the closing song on Clockwork Angels, “The Garden.” Here, he directly refers to Voltaire’s Candide, almost quoting Candide’s statement (also used by Leonard Nimoy in his last tweet shortly before his death) that regardless of grand notions about reality, “we must cultivate our garden.”

In the fullness of time,

A garden to nurture and protect.

The treasure of a life is a measure of love and respect,

The way you live,

The gifts that you give.

In the fullness of time

Is the only return that you expect.

This may not be comforting to people who want the measure to be a standard imposed by “some celestial voice,” as Peart called it in “Free Will,” but what he identifies here is indeed the only return we rationally can expect and the only one we can say we’ve earned.

The future disappears into memory,

With only a moment between.

Forever dwells in that moment,

Hope is what remains to be seen.

Hope is not defined in this song, but we can conclude from Peart’s other writings and from what “The Garden” does recommend, that the hope is for the continued existence and achievement of the human community, both in our families and in the wider world. And, of course, these things are dependent on our choices. Succeed or fail, it will be what we do that decides the question, and Peart does make the choice to be hopeful about where we’re headed.

Finally, Neil Peart’s character studies in the song “Losing It” are a reminder that we have to work on our gardens each day, since we have no guarantee of any time in the future. This is the choice to take personal responsibility for our lives now without waiting for some life to come, knowing that one day, we will leave the game. Rush’s lead vocalist and bassist, Geddy Lee, has suggested that future studio albums may come out with a reduced touring schedule, but even if that doesn’t come to pass, I do hope Peart the artist continues to express his celebration of humanism in some medium, even if it’s no longer music.