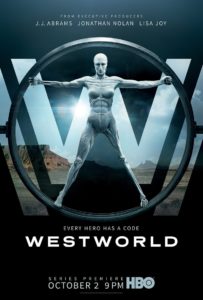

Review: Westworld, (HBO), Season One

Westworld Poster (HBO)

Westworld Poster (HBO) Westworld condenses the character, theme and plot developments of an entire television series into just its first season. No sooner do we discover that a character has the motivation to commit an act than they commit it. Hard philosophical questions on identity, consciousness, and the self are answered almost as quickly as they’re raised. Things that should’ve been revealed in season four are prematurely revealed in episode seven. After you’ve finished watching, you wonder where the show could possibly go after this. You’re probably also wondering how, given the precociousness of its plot, the season still manages to have such an abundance of superfluous and stretched-out scenes.

Based rather loosely on the eponymous 1973 science fiction film written and directed by Michael Crichton, the new show (which premiered on HBO in October) has a good deal more ambiguity and thematic eagerness than its cinematic counterpart. In the film, the park’s androids (“hosts” as they’re commonly called) malfunction and eventually start killing the guests. How the park’s management handles this crisis and their morally unscrupulous reasons for handling it as they do is the deeper meaning that underlies the film’s western-style action. The show, on the other hand, has a broader scope and much more ambitious aims, a combination that can make it difficult to hit anything singularly significant.

Robert Ford, played by Anthony Hopkins, is the megalomaniac director and co-founder of the park in HBO’s adaptation. Not based on anyone from Crichton’s original film, Ford best symbolizes the grand divergence between the two projects. Whereas in the film, the mayhem is a result of a “virus” getting into the hosts and spreading throughout the system, in the show Ford is pulling the strings throughout. It isn’t clear how over-arching his scheme is because it isn’t clear why he does the things he does. Greed is the sole malignant motivator in the film, but in the show all sorts of petty vices are in play. In the last episode, some of the confusion is cleared away; however, the overall picture still looks chaotic. Billed as a preamble to the actual story yet to come—the show is planned to last five seasons—what we’ve seen so far feels more like the ending to something with a past more interesting than its future.

Like many of its contemporaries, Westworld has been derided for its “moral ambiguity,” but what most critics have missed (or at least failed to acknowledge) are the many different types of moral ambiguity there are. For example, it’s one thing to demonstrate that the heroes don’t lack faults and that the villains don’t lack reasonable motives, and it’s something else entirely to make it unclear who the heroes and the villains are. One confronts the viewer’s moral intuitions while the other merely confuses them. The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, and Game of Thrones are inimitable televisual examples of the former, while Westworld is unfortunately exemplary of the latter.

The humans who visit the park are all rich, sadistic philistines while the humans who run it are all career-obsessed boors. The hosts on the whole are charming, devoted, and verbally pithy, except for the bandits, the soldiers and the occasional set of rogue Indians. At first it seems clear that viewers are meant to sympathize with the hosts—a typical quasi-populist message one finds in dramas involving artificial intelligence—until, that is, they start behaving like humans. At that point they become about as sympathetic as the cabinet members in a Tom Clancy novel.

In art, the use of religious jargon—if it’s used discretely—can add a certain density to what’s being said that couldn’t be packed in otherwise (likewise with psychoanalytic jargon, business jargon, or any other specialized language), but it can also be used to conceal an absence of genuine profundity. Not every time Westworld utilizes religious jargon is it in this second way, but after the fifth invocation of “sin” and the eighth invocation of the “devil,” one begins to detect a word pattern, which is either a sign of fatigue or laziness. “A prison of our sins” is a great way to describe an amusement park meant to gratify the rich’s every violent appetite, but saying, “You can’t play God without being acquainted with the devil,” isn’t particularly clever, nor is it teasing out the sentiment the screenwriter intends it to.

Many have expressed concern that Westworld will be the new Lost, eventually getting too wrapped up in its own plot twists until it’s faced with choosing between a consistent story or a compelling one. Another undesirable possibility is that it will get caught up in its own narrative momentum until it becomes merely silly and obnoxious, similar to the Resident Evil film franchise (this seems like the more likely outcome). Whatever the fate of its story, Westworld will undoubtedly still contain some of television’s best editing, composition, and design. The roles demand quite a bit from the actors, especially those playing the hosts—each of which give truly remarkable performances, including Jeffrey Wright, Evan Rachel Wood, and James Marsden.

A line from Romeo and Juliet that’s quoted in Westworld (Friar Laurence’s warning to Romeo) plays a significant role in the narrative: “These violent delights have violent ends.” It’s doubtful any of the producers realize its full context in the play, or else they’d see that it contains a prophetic indictment of the show, as the next line reads: “The sweetest honey is loathsome in his own deliciousness and in the taste confounds the appetite.” Were Westworld’s creators to reread Shakespeare, perhaps he might offer a lesson in moderation for the next season of a show that has, thus far, over-indulged.