The Good Wife Throws the Good Book at its Lead Character

Let’s begin with a bit of brutal honesty concerning U.S. politics: there are people who will refuse to vote for a political candidate purely because of their stance on or stock in atheism or humanism. Rather than taking the qualifications and abilities of the candidate into account and simply chalking up the difference in faith as a potential negative, this segment of the population chooses to believe that “godlessness” compromises an individual’s integrity and moral code to such a degree that they cannot fully or effectively execute all the duties of political office. Add to that the paranoid suspicion that atheists are conspiring to remove all elements of religion from America by obtaining a majority share in the government, and it seems very little good can come of the situation.

These dogmatic perceptions are, in a way, related to the negative stigma surrounding LGBT and female candidates as well—one might say that the negative associations around each are three heads of the same chimera. The stereotypes that form the absolute basis for these views are often perpetuated by a certain end of the political spectrum, but it’s in the portrayal of each of these demographics within popular culture that has the largest and longest-standing effect on the general population.

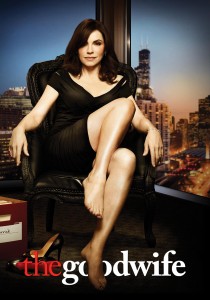

Enter The Good Wife, a highly praised CBS legal/political drama currently rolling through its sixth season. To its proverbial lapel it has attached a pin of progressivism, portraying the struggles of those who fit into certain monikers and titles. It boasts a cast diverse in race and gender whose members portray a wide variety of unique and deep characters (it hopes) who have kept the show running long past its original premise. The plot, now too complex for a throwaway summary, currently has lead character Alicia Florrick (Julianna Margulies) as a disgraced-political-wife-turned-lawyer and “on record” atheist working in a firm of primarily female litigators and investigators, including the witty and sometimes violent Kalinda Sharma (Archie Panjabi) and the regal Diane Lockhart (Christine Baranski). Sharma is bisexual, but her orientation is abused by the writers as a modern-age plot twister; she is shown in multiple sexual relationships with both men and women but her interactions with the latter are primarily work related. Rather than sleeping with them for personal pleasure, she seduces them to advance the current case beyond a rough patch. Florrick, meanwhile, was revealed as an atheist last year, inviting fresh interest to the show around the same time as a number of other explosive events went down, which won’t be spoiled for those yet to start the show. While Florrick’s atheism has been mentioned since its introduction, in the sixth episode of the newest season (aired October 26), it became more than a trait—it became a threat.

As a candidate for Illinois state’s attorney, Florrick is told that she will have to be interviewed on camera by a well-known pastor; it seems that speaking with this man of God is part of a candidate’s rite of passage, necessary to be taken seriously as a contender for the position. The episode opens with several bureaucrats (including, as part of a running gag on the show, at least one actual U.S. senator) indulging in their own religious diatribe with the pastor. Florrick’s associates do their best to groom her for the interview, with one proposing that she provide what the public wants to hear about her, rather than the truth.

At a later point in the episode, Florrick’s associates (by all indications, good friends of hers) attempt to pick out traumatic moments from previous episodes that could have inspired Florrick to have a religious epiphany so that she can say she had one, winning over voters. The way lying to the public is so casually discussed may be par for the course in a political drama, but that doesn’t make it any less unsettling when the death of an earlier character is mentioned as possible fodder. Florrick attempts her own input but is assured that voters will not pick her if she stands her ground. In the end, Florrick’s own daughter, Grace (a religious convert), ends up preparing her mother for the interview in the final stages, quizzing her on various terms of the faith. This does lead to a good moment where Grace reaffirms her love for her mother despite their differences in faith, but it still highlights the fact that only Florrick herself seems to find no fault in her stance as an atheist.

In the end, she makes it through the interview by saying that she is neither religious nor an atheist; when the pastor mentions her previously established position, she dismisses it and states that she is still seeking answers “outside of” herself. I remember declaring to the television (as always, to no avail) that the word the writers were searching for was agnosticism, but it never came up. Instead, a strong character was forced to plop down in some grey area and hope that she didn’t offend either side.

What does all this really mean, though? As mentioned, the fact that many voters are skeptical of atheism and its plethora of associated terminology remains true to this day, as it nearly always has. The show was, in a way, demonstrating the thin line that atheist political candidates do need to walk if their way of thinking has been made public; if it hasn’t, such a truth is often confined to the shadows of secrecy. Can The Good Wife really be berated for showing a reality, even if it’s a sad one?

In my honest opinion, it can. Television has served as an unprecedented way of delivering a message. Super Bowl advertisements are some of the most grandiose and expensive productions in marketing, all to draw attention to names and products. Broadcasts have decided more than one election, even at the presidential level, and the back-and-forth between FOX and CNN has become the poster-child for conservative/liberal animosity. It could have been very different if Florrick’s associates and friends had been written to support her in spite of voter’s tastes, rather than attempt to change her to suit them. It could have been different if a world had been shown where people were more accepting of an atheist running for and holding public office; imagine how many minds might have been persuaded, or at the very least pricked to consider the possibility of accepting atheism, even begrudgingly. Like Captain Kirk’s kiss with Uhura on Star Trek—television’s first interracial coupling—opinion could have been changed, or at least inspired a more positive attitude towards atheism, a group of people so often construed as negative and spiteful. Things could have been very different if the writers of The Good Wife had not treated atheism as some pox the public must be hidden from, but as a trait of a character that could be accepted. For a show that seems to have so many progressive elements, the attitude towards atheism shown here felt like a step backwards.