TV Review: Wild, Wild Country

Wild, Wild County, the six-part Netflix documentary series, is much like its main character, Ma Anand Sheela: dark, complicated, multi-layered, and mysterious.

On one level, the documentary is a story about a crazy criminal cult run amok in the rural Pacific Northwest. On another level, one the makers of the series don’t seem to fully understand, it’s a story of white, traditionalist Americans terrified of being overrun by the “threatening outsiders” of marginalized communities.

Some people may remember the story of the Rajneeshees in Oregon, a cult that made international headlines in the 1980s when they bought an isolated ranch, built a town, and tried to take over a county. Their tale has everything: sex, politics, attempted murder, mass poisonings, land grabs, ninety-three Rolls-Royces, international flights from the law, questions of separation of church and state, and racial and cultural divides exploited by both sides.

The Rajneeshees were founded in India in the second half of the twentieth century by a charismatic, self-styled guru who called himself Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (later Osho). Preaching the joys of capitalism, playfulness, joy, and a particularly vigorous form of meditation as the path to spiritual enlightenment, Bhagwan attracted a diverse, international group of devoted followers—called sannyasins—to his commune in India. Bhagwan vacillated over calling his organization a religion, labelling it that at times but later eschewing the description and going so far as to burn the books that set forth the precepts and rules that “worshippers” should follow. What’s certainly true is that outsiders both in India and the United States saw it as a religious cult—and a dangerous one at that.

The group (or religion or cult) left India when the government there started looking into possible tax and land fraud as well as reports of prostitution and drug smuggling. In the early 1980s, under the guidance of Bhagwan’s second-in-command Ma Anand Sheela, the organization bought the Big Muddy Ranch in Oregon with an elaborate plan to build a new kind of community as the home base and headquarters of the group. The white, largely retired residents of the ranch’s nearest neighbor, the tiny town of Antelope (population forty), were at first bemused and then horrified by the people they saw coming into their town on the way to the ranch.

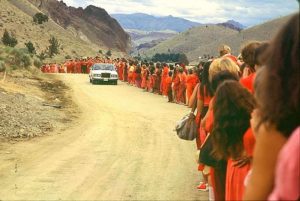

Certainly, the sannyasins didn’t look like their new neighbors. In contrast to the quiet, conservative townspeople and farmers around them, the sannyasins were a diverse, multi-ethnic group; clad entirely in red, pink, and purple clothing and often seen dancing and twirling in the streets. They practiced free sex and didn’t form traditional marital relationships. The residents of Antelope didn’t know how to respond to them and, as is clear from the documentary, they didn’t even try.

The Antelope mayor, in news clips featured in the documentary, makes statements like, “These people aren’t like us.” It’s this attitude—that the existing residents have a right to the land and the strangers should fall in line or leave—that prompts an angry Sheela to describe the local attitude as a “Mayflower mentality.”

Local neighbors became more concerned when, in short order, the Rajneeshees turned the rocky, hilly pastoral ranch they had purchased into an intentional community that included houses, a meditation center, a mall, restaurants, a clinic, a fire station, and a police force. They even built a club and casino for the seven-thousand sannyasins that would eventually live there.

When the group at the ranch was big enough they voted to incorporate the area as a town and named it “Rajneeshpurum.” When Antelope residents tried to fight these changes, the Rajneeshees bought enough property in town to gain the majority. They took over the Antelope town council seats in the next local election, in a victory over local efforts to dis-incorporate (the slogan of which was “Better Dead than Red”). Now in power, the group renamed the city of Antelope “Rajneesh.” (It’s not depicted in the series, but they also raised property taxes in Antelope to enrich themselves and enacted a series of initiatives designed only to infuriate Antelope residents, including renaming the local recycling center the Adolf Hitler Recycling Center.)

The Rajneeshees next set their sights on Wasco County, where a portion of their ranch was located. And this is where things get really “wild.” In the fight to take over the county government, Sheela and her followers employed tactics that included mass food poisoning, arson, attempted murder, and packing the voter rolls with homeless people brought in by bus from around the United States.

The state of Oregon, and eventually the federal authorities, reacted with prosecutions for crimes including attempted murder as well as immigration and tax fraud. Interestingly for those of us concerned about the separation of church and state, early attempts by the state to stop the growth of the organization were based on Establishment Clause arguments that a religious organization could not control the town governments of Rajneeshpurum and Antelope/Rajneesh or directly interfere in their elections. Unfortunately, these attempts are only briefly mentioned in the documentary.

The series is compelling, prime binge-watching fodder. It’s well worth your time. And if you can set aside six to seven hours consider doing so, because it’s difficult to stop in the middle. You can certainly watch it just for the sensational story of the Rajneeshees and their crimes and excesses. The Rajneeshee, led by both Bhagwan and Ma Anand Sheela, undeniably commit criminal, even evil acts and terrorize at least two counties in the process. It’s undeniably fascinating to watch their rise and fall and the federal prosecutors that bring them down.

As I alluded to earlier, there’s another disturbing dynamic at work in the story.. Although they don’t examine it in the documentary, the directors apparently did recognize the problematic motives of some of the neighbors. In an interview with the digital magazine Vulture (after Wild, Wild Country was released) the directors, brothers Chapman and Maclain Way, said:

It’s one of those things where, yes I think there was probably some bigotry, either conscious or unconscious, on the part of some of the people who lived there. But obviously, the Rajneeshees were doing things that were not right. So you can understand why people were skeptical of them. It’s possible for multiple things to be true at once.

That’s certainly true. The problem is that the “skepticism” of the neighbors started long before there was any evidence that the Rajneeshees were doing anything wrong. So, when you watch, look for the undercurrents that the makers of Wild, Wild Country don’t necessarily want to examine: the fear of “the other” that is prominent in so much of the early reaction against the Rajneeshee and a force that remains sadly untamed in our country today.