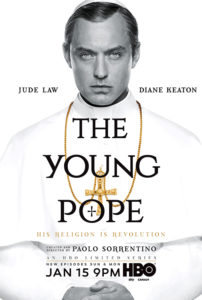

TV Review: The Young Pope’s Godless Confession

The Young Pope, a ten-part HBO drama written and directed by Italian filmmaker Paolo Sorrentino, follows the ascension of the young and captivating Lenny Belardo (Pope Pius XIII), the first American pontiff. The newly elected pope, portrayed by Jude Law, quickly proves to be anything but the young, inexperienced, and malleable figure the College of Cardinals thought he’d be. What follows is a rich narrative that reveals the Vatican as a political circus comparable in subterfuge and intrigue to Washington, DC.

The show is visually stunning, and its picturesque use of symbolism is apt for its subject and even rivals that of the church. The series begins with a dream sequence in which Belardo emerges from under a mound of dying babies as Pope Pius XIII—victor. This image, resembling conception, reveals his infantile qualities while alluding to his resolute and capable nature. Although extreme, this type of surrealist imagery is present throughout the series, along with more subtle cinematic queues, which combine to create (at least in image) a beautiful work of art.

As the title suggests, at forty-seven years old, Belardo (who insists on being called Holy Father, even by his longest and most intimate relations) is one of the youngest elected pontiffs in history. His papacy is the result of an effective internal campaign within the Vatican to presumably elect a young “liberal” and amenable leader of the church. However, Pius XIII quickly makes clear to them that he is sovereign and will not be easily influenced—if at all. This is perhaps made most clear in one of the early episodes where he meets with Cardinal Angelo Voiello (Silvio Orlando). Upon lighting a cigarette, Voiello reminds Pius XIII that Pope John Paul II banned smoking within the walls of the Vatican. Pius pointedly responds, “I’m the pope now.”

It appears that Sorrentino did not intend to write a story about a young man rising to the occasion of his celebrity. Instead, the title of the show is both a literal and symbolic representation of Belardo’s character. It’s revealed early on that as a child, Belardo was abandoned by his parents and subsequently grew up in an orphanage under the care of Sister Mary (Diane Keaton). This experience has an intense and undying effect on Belardo: being forced to grow up fast has rendered him an infantile adult. His early abandonment also informs severely conservative viewpoints. In his first homily, that distresses the entirety of the “liberal leaning” Vatican, Belardo demands that Catholics must devote themselves to God, no matter the extreme and regardless of consequence.

The duplicity in Belardo’s character is both disorienting and at times, intangible. Viewers of the show may find themselves just as suspicious and in awe of Belardo as the Cardinals themselves. He is vile and vindictive, calculated and revengeful. He purposefully offends nearly everyone he meets, forces his colleagues to sin for his own political gain, and excommunicates whomever he feels like—especially for presumed “homosexual tendencies.” However, he does have rare moments of insight and grace, albeit short-lived. For example, upon learning that a nun’s sister died, he arranges for her body to be brought to the Vatican for burial so the nun does not have to travel to the country she ran away from. But when the nun cries at her sister’s funeral, Belardo publicly berates her and to her dismay, accuses her of lacking true faith.

The theme of contradiction weaves itself into the narrative of the Vatican. A character within itself, we see it struggle to keep up with the modern world. The church, even outside of the show, struggles to remain relevant and reconcile its antiquated philosophy with popular modern progressive thought. A young pope presents an opportunity to bridge conflicting parties, but Pius XIII serves only to divorce them further. He can at once be inspired by Daft Punk and Banksy while comparing Catholicism in Greenland to the Native American genocide. He can demand the strictest adherence to God from his followers, while committing lush and devious sin. Is it possible for someone to dedicate their being to God as he does, while staying relevant? Furthermore, is it possible for someone to dedicate their being to God as he does, and still believe in a divine creator?

The answer might just be no. After forcing a member of the Church to commit sin on his behalf, Belardo confesses to him that he does not believe in God. He quickly masks it as a joke, but the audience is left to question his intentions. We never truly believe Belardo because we can’t trust him. Like the religion he espouses, he is full of contradiction and is largely unpredictable. Midway through the season, audiences still don’t know what kind of man they are dealing with. Although it’s clear he has a plan for the future of the Vatican, his motivations have not yet been revealed to us. The poster for the series reads, “His religion is revolution,” but for what change does the young pope aspire to?

Overall, Sorrentino has created a compelling character not unlike Frank Underwood in House of Cards—a complex and charming antihero. But who is he a villain to, progressive philosophy or Catholicism? Only time will reveal just how deep into the framework of the great halls of the Vatican Belardo’s story goes, but it’s worth sticking around for.