We Owe Our Children Quality Educational TV

Photo by haywiremedia / 123RF

Photo by haywiremedia / 123RF I did not want for quality educational programming when I was a child. I was surrounded with the likes of Bill Nye “The Science Guy” and Ms. Frizzle, and even Sesame Street—which I’d watch once before catching the bus to go to kindergarten and once again after school. These programs showed me a wider world that I couldn’t wait to take part in once I got older.

Fast forward nearly twenty years and we’re looking at a practically barren landscape of scientific programming aimed at children. Bill Nye has graduated to educating superstitious old men instead of grade school kids, and Ms. Frizzle has been in hiding since The Magic School Bus wrapped in 1997.

It’s not all bad, though. Seth MacFarlane, of all people, helped get this year’s revival of Carl Sagan’s Cosmos off the ground, and led it to a number of well-earned Emmy wins. Even Ms. Frizzle is getting the reboot she deserves: The Magic School Bus 360° will air on Netflix in 2016.

Hopefully kids are getting at least some quality educational programming in between SpongeBob marathons, but history is not on our side: Back in 2008, a University of Arizona study concluded that only one in eight children’s educational programs were of “high quality.” Clearly we’re still in the recovery period.

Maybe I can attribute it to the rose-colored glasses of childhood, but it seemed like I was always learning when I was a child—yes, even while I was in front of the television. Unfortunately, we seem to be collectively focused on other problems instead. Parents seem to be panicking on a massive scale when it comes to, for example, kids accruing huge bills for unauthorized in-app purchases on their phones and tablets, a problem that wouldn’t exist if we found age-appropriate and worthwhile ways to entertain our children instead of buying them the latest gadgets.

And yet, as instructive and essential as this kind of programming was to me as a kid, it was still accompanied by all of the familiar Christian superstitions that most of my family holds to even now. I spent my Sunday mornings in church, nodding along to the same empty platitudes that seemed never to be spoken with any real conviction, or in a way that had any relevance to my life.

And yet, I still had a chance. I still had resources at my disposal that would help me grow into an endlessly curious child. These TV personalities—the Bill Nyes and Ms. Frizzles—would stay with me for decades.

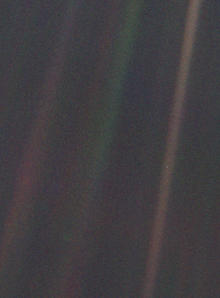

It was during my long years of grade school that I would see a particular image brandished again and again as though it contained the key that would unlock the secrets of the universe. You’ve probably seen it too:

It doesn’t look like much, does it? You’ve likely heard the phrase “pale blue dot” on a number of occasions, and here it is: that tiny dot is earth, existing exactly where it needs to be in order to sustain human life. I’ve seen it so many times, and it always seems to be introduced with the same hushed, reverential tones: Our God is good. Look what he’s made for us.

I realized while I watched Cosmos earlier this year that Neil deGrasse Tyson has a way about him that made him the perfect choice to host the show. He manages to casually dismantle the most popular arguments of creationists but does it in a way that never sounds condescending or judgmental. So when he called on the image of the pale blue dot to drive his point home, I sat up and took notice.

When Tyson showed us that famous picture, I found myself thinking differently about it, for perhaps the first time in my life. Instead of telling myself how good our God is to bless us so, I thought instead about how damned narcissistic it is to believe that we’re special in this unimaginably vast universe. And then I realized that that type of narcissism has been steering the course of human development since the dark ages.

During the final moments of Cosmos’ final episode, “Unafraid of the Dark,” I found myself trembling. A lifetime of pent-up frustration and doubt was washed away, and I believed, for the very first time, that I had no use for a god in my life. Like the child of an absentee father, I got tired of waiting for him to come home to me.

Your results may vary. And I’m not going to claim that the goal of Cosmos was to shatter leftover childhood beliefs in God—it served only the truth, which so often can be found nowhere else other than in conversations about our collective cluelessness. Indeed, for all of our seemingly perpetual scientific innovation, we thoroughly understand only the tiniest fraction of the natural world around us. And so hitching a ride on the Magic School Bus became, of all things, a gesture of humility for childhood-me. And then I went back to church on Sundays and was told that the book in my hands had all the answers I would ever need. What a disappointment.

I’m not saying that I want to recruit every child in America to the cause of atheism; in fact, there’s no reason why faith and science need to be mutually exclusive. What I want to see instead is more programming like what I had as a child: informative and entertaining, yes, but more than that it needs to inspire wonder. The Christian Bible inspires wonder, too, but its particular variation is, to be blunt, an intellectual dead end. I want children to be able to explore the vastness of creation without the baggage of fear and closed-mindedness and superstition. I want them to be able to choose truth, should they desire to do so.

And if they choose a god instead, that’s fine too—we all need our comforts. It would be enough for me to know that they at least had the same chance I did.