A Belle with a Lot on the Ball

The words “based on the inspiring true story” roll nicely off the tongue, but when little is known of that true story beyond a painting, a few diary references, and some prominent court cases, creative license has its day. And so we see in the new film Belle a work of historical fiction. But it is humanist historical fiction.

First the historical part.

Dido Elizabeth Belle was the daughter of an African slave woman, Maria Belle, and British Captain John Lindsay. Though Lindsay never married Dido’s mother, he freely declared Dido to be his daughter, gave her his last name, and placed her in the home of his uncle, William Murray (the 1st Earl of Mansfield), to receive an aristocratic upbringing. Evidence that such was provided is found in the painting, commissioned by Murray in 1779 and hung prominently in the family manor, showing Dido with Elizabeth Murray, a cousin with whom she was reared. As for Captain Lindsay, later a knighted admiral, he died at sea but left Dido sufficient inheritance to render her well off.

Then there are two abolitionist legal cases over which William Murray, as Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, presided. The first was Somerset v Stewart in 1772, wherein the court held that no persons, even slaves, could be removed from England against their will. The second was a series of trials that followed the Zong massacre.

In December 1781, the crew of the British slave ship Zong threw approximately 140 African slaves overboard in order to save the rest from thirst and disease. Afterwards, the ship’s captain demanded his insurer pay for this loss of human cargo under the principle of “general average,” where a captain forced by circumstances to jettison part of a cargo to save the rest can make an insurance claim. But the insurer refused to pay for murder, so the case went to court. In the final trial William Murray ruled narrowly in favor of the insurer, declaring that the captain and crew had mismanaged the entire voyage. They were thus themselves responsible for the situation that had occurred (though they were never convicted of murder in any criminal proceeding).

Now to the fiction.

In the film these cases are conflated. Then they are combined with a thought-provoking family drama, enacted—after the fashion of Jane Austen—within the starched confines of aristocratic propriety.

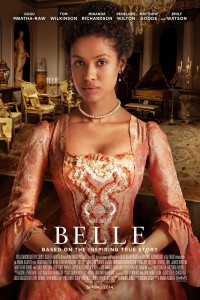

So we see Dido (played by Gugu Mbatha-Raw) forced to navigate the line between, on the one hand, her illegitimate birth coupled with her socially disparaged color and, on the other, her patrimonial rights and privileges. At one point she complains how she is considered too high to eat with the help but too low to join the family at dinner when visitors call. Her aunt, Lady Mansfield (Emily Watson), anticipates that Dido will die an old maid because no man of her station would dare ruin his family reputation by marrying her; and if she were to marry the sort who would accept her, it would be at the cost of her descent to his lower status.

With such racial and domestic conflicts, this all could easily have become the stuff of melodrama. But in a refreshing departure from the “tragic mulatto” trope recycled over the past century of filmmaking, director Amma Asante and screenwriter Misan Sagay allow Dido to emerge as a talented and courageous woman capable not only of making her own choices but of influencing those of others.

Soon after she meets John Davinier (Sam Reid)—a vicar’s son who prefers the practice of law to faith and pursues social progress over religious and class traditions—she reacts with avid curiosity about his advocacy of justice in the wake of the Zong massacre. By contrast, William Murray (Tom Wilkinson), as her guardian, seeks to shelter her from such harsh realities. Dido will have none of the latter. She forms a secret alliance with John, provides him with documents in William’s possession that strengthen John’s legal arguments, then works to raise William’s consciousness of the utter inhumanity of treating human beings as property.

Despite the inescapable modernity of some of the sentiments, and utter illegality of Dido and John’s clandestine activities, the execution of the story is handled with so much subtlety and circumstance that one can almost believe it might really have happened that way—that in late eighteenth-century England Dido Elizabeth Belle Lindsay, conspiring with her radical abolitionist beau John Davinier, influenced a watershed court decision by the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales which ultimately led to the abolition of slavery in Britain.

The world, of course, doesn’t work like that. But such historical fiction serves as a microcosm in time and space of what really does occur, compressing history and all its players into a shorter span with a smaller cast so we can readily grasp the inspiring majesty of what people of patience and determination can gradually accomplish together. Thus Belle is an uplifting film for all who care about enlightenment and progress.

It isn’t pulse rousing, however. It doesn’t induce cheering or chest-thumping. Viewers won’t rush out of the theater eager to change the world. This is because Belle avoids depictions of villainy (in all but one relatively minor character). It prefers instead to let its characters grow in understanding or falter in their ways. Thus its mood is more sympathetic and sentimental and its pace more stately. We are likewise spared white-knuckled horse chases, heated shouting matches, and swashbuckling violence. These are replaced by low decibel personal and family struggles and a well-groomed conflict of ideas.

Which means Belle will likely be relegated to art houses and won’t be in theaters long. Hence I recommend you see it immediately!