Film Review: Best of Enemies

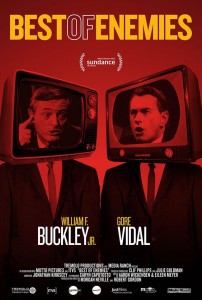

If there is, by chance, an omnipotent being lurking around up there—somewhere out in the vast cosmic expanse—I imagine that, after creating the cosmos, the Earth, and all the living things upon it, this god got bored and eventually created Gore Vidal and William F. Buckley Jr., and then set them in opposition just to see what would happen. The near-mythological Shakespearean tragedy that unfolded throughout their nationally televised debates in August 1968—created by ABC to be aired around the Democratic and Republican national conventions—was certainly a spectacle for those who witnessed the original collision. Now, thanks to Robert Gordon and Morgan Neville’s new documentary Best of Enemies (coming to theaters July 31), we can witness the collision again or anew.

Gordon and Neville manage to bring a sensational (and worthy) gravitas to an already culturally significant event. And they do it without being heavy-handed—mainly because the debates themselves—brutal Olympian displays of verbal blood sport—and the chaotic sociopolitical backdrop against which they played out, carry enough weight on their own. Instead, the filmmakers work to weave a rich tapestry of archival footage and guest commentary (including some from the late contrarian Christopher Hitchens). The final product is an energetic, cerebral, and rather hilarious (but ultimately sobering) narrative that explores, with sophisticated restraint, the lives of two public intellectuals and the worlds and ideologies that characterized them. It’s a colorful and engaging portal to the political past, with each of the infamous debates introduced by a title card and the round-starting ring of a boxing bell—each one another tick off the timer on the bomb that would eventually explode in the seventh round.

Best of Enemies does a masterful job building to this moment, constantly ratcheting up the stakes, lurching ever-forward towards an inevitable climax—a march that, if you know what’s coming, is filled with both dread and eager anticipation. Debate seven, the penultimate debate, was, in Buckley’s own words, a moment that “rocked television.” But it did much more. In that brief moment at 9:39 EST, on August 28, 1968, one can witness the birth of the modern American culture wars: a conservative and a liberal who don’t just disagree ideologically but who hate each other personally, intimately, and who, in reflecting on lifestyles, can no longer even agree on what it means to be a good person.

It’s often said that William Buckley did much to lay the intellectual foundations for the modern Republican Party. The man was also an admitted white supremacist and a homophobe—but it was particularly in the moment when he called Gore Vidal a “queer” on national television, and then, like some juvenile bully, threatened to punch him in the face, that I could imagine a light bulb going off over the head of a young Rush Limbaugh. It was the opening scene in the theater of the absurd that is the current news media.

It’s fitting—perhaps too fitting—that this cultural paradigm shift occurred precisely during the unrest, revolt, and police brutality of the 1968 Chicago riots: a maelstrom of racial violence, anti-war rhetoric, and class upheaval that is all too familiar to many of the incidents occurring now. It’s one of the infinite ways in which Best of Enemies, a documentary about a forty-seven-year-old TV publicity stunt, is stunningly, horrifyingly relevant today. Those who see the film will notice the propaganda draped over lecterns as the footage makes its way through old elections and campaigns; notice the comments and quips from old politicians and commentators; and notice how, through almost fifty years of cultural and political turmoil, nothing has changed at all.

Best of Enemies succeeds as political commentary because it’s relevant, engaging, sophisticated, and informed. It succeeds as art because, ultimately, it’s the story of two men who had encountered in each other the utter negation of their strongest convictions—men who would impact both the world and themselves in the battle to defend them. Few movies can elicit such a range of emotion from an audience; Best of Enemies is at once funnier than most comedies I’ve seen and sadder than most dramas. It romps—confidently, joyfully—through the wit and intellect of two of America’s most learned and notorious pundits, and you laugh, loud and hard. It tempers that glee with a sober lament over the state of American culture, and you are silent.

I’ve used the word “collision” to describe what happened during the 1968 televised debates between Vidal and Buckley, but maybe collision isn’t the right word after all as it implies a kind of violent randomness. Watching this film, I got the impression that what occurred between these two monoliths was anything but random. Their showdown during the 1968 political conventions—presented and contextualized expertly by the filmmakers—played out less like the explosion of a violent collision and more like the calculated final battle between two eternal foes—“matter and anti-matter,” to steal a phrase from the film—each existing as the singular antithesis to the other, sharing only in a mutually perfect hatred and a desire for total, existential victory.

Gordon and Neville give us a glimpse of the aftermath of those debates—enough to know that, if victory was achieved on either end, it was unquestionably a pyrrhic one. The encounter haunted both men—almost relentlessly—until the day they died, riddling Buckley with an overwhelming guilt and driving Vidal to a near-manic obsession and a cold, cynical bitterness. The movie at its close treats us to one last jab from Vidal commenting on Buckley’s death: “I thought hell is bound to be a livelier place as he joins, forever, those whom he served in life, applauding their prejudices and fanning their hatred”—a moment that forced a quiet gasp from the audience in the theater. The political is the personal, they say—and Best of Enemies does much to remind us of that.